|

|

|  Since

the mid-1990s, a multinational conservation team has strived to reintroduce

magpie robins to other Seychelles islands where they once thrived.

Since

the mid-1990s, a multinational conservation team has strived to reintroduce

magpie robins to other Seychelles islands where they once thrived.

|

Saving the Magpie Robin

Part 2 | back to Part 1

This early success gave the team the

confidence to try reintroducing the species to other islands where it formerly

lived. In 1994, they established a population on Cousin, a 70-acre island that

had become a nature reserve in 1968. Three decades of conservation work have

restored the plantation island to native forest, which teems with wildlife and

has proven to be a perfect home for the magpie robins. An initial group of nine

birds translocated in 1994 has grown to 27. In 1996, we also seeded a new

population on the island of Cousine, which is just south of and slightly

smaller than Cousin. Cousine is a private island managed for conservation, with

a small hotel specializing in ecotourism.

Interestingly, Cousin and Cousine have played key roles in an earlier, fruitful

pulling-back-from-the-brink. By 1959, the endemic Seychelles warbler had

dwindled to about 30 individuals. By 1987, following stringent conservation

measures, the population had soared to almost 400 birds, and three years later,

the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) removed the

Seychelles warbler from its Red Data list of threatened species.

Only a single magpie robin—a female—survived the most recent introduction to Aride, though with help

from BirdLife Seychelles, a male joined her there in early 2000.

Only a single magpie robin—a female—survived the most recent introduction to Aride, though with help

from BirdLife Seychelles, a male joined her there in early 2000.

|

|

The one

island that has eluded us is Aride. This mile-long scrap of granite has been

called the Seabird Citadel of the Indian Ocean. Ten species reside here,

including the sooty tern, the red-tailed tropicbird, and the world's largest

colony of the lesser noddy. Aride also once hosted a thriving population of

Seychelles magpie robins, which snatched up fish dropped by the seabirds.

Unfortunately, several reintroductions have failed since that first attempt in

the 1970s. We know that a major predator of Seychelles magpie robins there is

the barn owl, which, ironically enough, was introduced in the 1950s to control

rats, another robin killer. Poor habitat, pesticides, and bacterial infections

may also be to blame, but currently we're unable to finger the chief culprit or

culprits using the available data. Today only one pair resides on Aride, but

research is ongoing.

Looking up

Despite the failure on Aride, prospects for the Seychelles magpie robin are brighter

today than ever before. On January 1, 1998, BirdLife Seychelles, a newly formed

nongovernmental organization (NGO), assumed management of the Recovery Program.

We feel this is crucial for success, for while expatriate scientists provided

vital technical assistance in saving the species from immediate doom, only a

local NGO can achieve long-term sustainability. That is, local people can best

teach local people how to do things better.

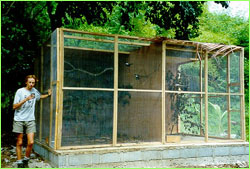

|  Science coordinator James Millet

stands next to one of two recently built

aviaries on Frégate.

Science coordinator James Millet

stands next to one of two recently built

aviaries on Frégate.

|

In 1998, we also formed the

Seychelles Magpie Robin Recovery Team, or SMART. This group comprises BirdLife

Seychelles staff members, island owners and managers, and government officials,

who make decisions by consensus in conjunction with a technical advisory

committee based in the United Kingdom. We have also strengthened partnerships

with overseas institutions such as the New Zealand Department of Conservation

and the Zoological Society of London, which provide captive and health

management assistance, respectively.

We have strived as well to build awareness locally among

Seychellois. Most of the roughly 10,000 visitors to Cousin in 1999 had the

opportunity to see Seychelles magpie robins and learn of our conservation

efforts, for example, while tourists on Frégate can avail themselves of

weekly tours and lectures. Recently, six articles on the Seychelles magpie

robin appeared in the national newspaper The Nation, and a segment on

translocating the birds aired on television. We published a full-color brochure

and a newsletter, both of which we've distributed widely, and we put up a

display at our country's Natural History Museum.

Naturally, we have also

continued our efforts to protect the Seychelles magpie robin. When

translocating birds from one island to another, we previously relied on a

'hard' release method: capture and caging, transfer by helicopter, and release.

But when we realized that this could stress the birds, we began opting for a

'soft' version. This features captivity for two to three weeks before transfer

and a further week of captivity on the new island before release, which now

includes supplementary feeding.

A BirdLife

Seychelles brochure proclaims the group's motto: "Safe But Not Yet

Secure."

A BirdLife

Seychelles brochure proclaims the group's motto: "Safe But Not Yet

Secure."

|

|

Two aviaries we built recently have

already more than paid for the time and effort we put into them. In November

1999, a young female with a broken bill turned up on Frégate. We placed

her in an aviary and fed her a combination of live prey and supplemental food.

She adapted well and soon had increased her weight by 15 percent. And in 2000,

we held the entire population of magpie robins on Frégate in the

aviaries for four months while we eradicated rats accidentally introduced there

in 1996 during tourist development.

Getting to safe

As I intimated earlier, however,

the Seychelles magpie robin is not out of the woods yet. Or should I say back

in the woods. Forest restoration must continue, and habitat loss is only

one of many threats still facing the species. Rats and cats can be accidentally

reintroduced; novel diseases like avian malaria, which decimated the birds of

Hawaii, can appear; and alien plants can quickly dominate the landscape,

disrupting the natural order of things. Inappropriate development,

unsympathetic managers, a downturn in tourism or international donor funding—all could potentially rend our fragile safety net.

With monies now on the way from the World Bank-funded Global Environment Facility, we hope to

establish populations of Seychelles magpie robins on several more predator-free

islands. Our goal is seven islands—including the current three and with four

of them self-sustaining—by 2006, with a total population of 200 birds. Only

then would we consider lopping off the last four words of our

motto.

|

|

Dr. Nirmal Shah is chief executive of BirdLife Seychelles, an

NGO committed to safeguarding the Seychelles magpie robin. For more

information, contact BirdLife Seychelles at P.O. Box 1310, Victoria,

Mahé, Republic of Seychelles. |

Photos: (7-9) Courtesy of BirdLife Seychelles.

Seychelles Through Time |

Saving the Magpie Robin

Why Do Islands Breed Giants? |

Build an Island

Resources |

Transcript |

Site Map |

Garden of Eden Home

Editor's Picks |

Previous Sites |

Join Us/E-mail |

TV/Web Schedule

About NOVA |

Teachers |

Site Map |

Shop |

Jobs |

Search |

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

© | Updated November 2000

|

|

|