Vaccines—Calling the Shots

Examine the science behind vaccinations, the return of preventable diseases, and the risks of opting out. Airing August 26, 2015 at 9 pm on PBS Aired August 26, 2015 on PBS

- Originally aired 09.10.14

Program Description

Transcript

Vaccines—Calling the Shots

PBS Airdate: September 10, 2014

NARRATOR: Our lives are linked as never before, connected every day in a thousand unseen ways. But sometimes, these connections can pose an invisible threat, if the object we touch, or the air we share, carries a dangerous germ.

DR. SIMON FENSTERSZAUB (Quality Health Center): You don't have to cough, you just have to breathe. It's the worst kind of contagion: it's airborne.

NARRATOR: Diseases largely unseen for a generation, are returning.

SIMON FENSTERSZAUB: This can't be. This child looks like she has measles. This is New York. You don't see measles in New York!

DR. JANE ZUCKER (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene): It's astounding to me that you can have people dying of measles in the developed world.

NARRATOR: Today, children are getting sick and dying from preventable diseases, as nervous parents skip their children's shots.

ALISON SINGER (Autism Science Foundation): You are injecting a substance into your child, so, I think it's very natural to wonder whether that substance might actually be doing harm.

YULIA PATSAY (Mother): There's just so much information there, and I don't, I don't know who to ask. Who am I supposed to trust?

NARRATOR: In a world of often conflicting information, parents are seeking what's best for their families, while doctors worry about losing lives.

DR. PAUL OFFIT (Children's Hospital of Philadelphia): Your job is to try and save children's lives, and when you stand helplessly by and watch them die, it gets to you.

DR. AMY MIDDLEMAN (University of Oklahoma): We ask a lot of parents. We ask them to trust that we are recommending the best thing for their children. That's a big deal.

NARRATOR: The science behind vaccines: why they work, how they work and how we decide to vaccinate or not…

DR. BRIAN ZIKMUND-FISHER (University of Michigan): It's not about saying, "Oh, my gosh, I'm afraid," and now that's the end of the conversation. No, that's just the start of the conversation.

NARRATOR: …Vaccines—Calling The Shots, right now, on NOVA.

Happy, healthy children, it's what every parent wants. And, in this era of modern medicine, it's what most parents expect. Many dangerous diseases have all but disappeared, thanks, in good part, to vaccination.

In the U.S., more than 90 percent of parents vaccinate their children, and most follow the recommended schedule. That's up to 28 immunizations in the first two years of life, to protect against 14 different diseases.

But today, powerful concerns are in circulation.

GABRIELLA MAKSTMAN (Mother): I'm concerned about how many vaccines we have to give our children at once.

MARIANNA FASTOVSKY (Mother): So, I'm kind of debating whether I will do them, but I'm also debating the age. When should I have them done?

YULIA PATSAY: There's just so much information there, and I don't, I don't know who to ask. There's no such thing as an unbiased source.

NARRATOR: At least 10 percent of parents delay or skip some shots; around one percent don't vaccinate at all. And in some places it's far higher. What's driving some people away from vaccines? And what are the consequences for those who vaccinate and those who don't.

Osman Chandab is seven weeks old. He was due to be vaccinated against whooping cough in the next week, but the germ has gotten to him first. His mother brought him to the hospital two days ago. What started as a runny nose and slight cough has become frightening episodes where he's struggling to breathe.

Whooping cough, or pertussis, as it's formally known, can be life-threatening for babies.

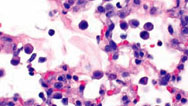

DR. DARYL EFRON (Royal Children's Hospital, Melbourne, Australia): Whooping cough is caused by a really nasty bacteria called Bordetella pertussis, and that produces a toxin that attacks the airways and causes a really nasty bronchitis. And they get really sticky, thick phlegm that they can't shift, and they try to and that causes them to cough.

And the cough needs to be really, really vigorous, but they often…it's not very effective, and then, sometimes, they stop breathing. And if they stop breathing for long enough, they go red in the face at first and then sometimes, if it's an extended period of not breathing, they can go blue, and that can be very, very frightening.

NARRATOR: Half of all infants younger than one will be hospitalized; about one in 100 dies.

Antibiotics can reduce the chance of infecting others, but there is no cure. Osman's tiny body must fight the illness.

A generation ago, whooping cough was rarely seen in developed countries. Now it's back. In 2012, there were nearly 50,000 cases in the U.S. and 20 deaths. Babies too young to get the pertussis shot may have no protection. And because the vaccine's effectiveness can wear off after a few years, older children and adults without boosters are also vulnerable.

Since the beginning of our young century there have been outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, flaring up like so many wildfires. In 2011, there were over 30,000 measles cases across Europe. Although the disease is often mild, thousands had serious complications; eight died.

In 2012, the outbreak continued in the United Kingdom; in 2013, it made the leap to the United States. A young American travelled from London to Brooklyn, infected with the virus. He returned home to his tight-knit Orthodox community, where most people vaccinate, but he came from a group of families strongly opposed to vaccines. Measles quickly spread through unvaccinated families living in the same building and then out into the community.

Children were hardest hit, especially those too young to be vaccinated.

SIMON FENSTERSZAUB: The first case that, that I saw was a 12-month-old girl that came into the office with mom, because of a rash. And I'm looking at this child, examining this child, and I was like "This can't be. This child actually has measles." And I've never actually seen measles, but, uh, I've seen them in textbooks, never in real life, so I was a little taken aback.

Three or four days later, perhaps, we have another case and then the next day, another case and then another one. And it just, it started getting overwhelming. Now wait a second.

NARRATOR: The Department of Health tried to stop the spread.

JANE ZUCKER: The thing about measles is, you know, it's droplet-spread. So, for example, you know, your respiratory secretions, if someone coughs, but it's also airborne. So the virus can sort of hang out in the air for up to two hours.

NARRATOR: One case was traced back to an infected person taking the elevator up to an apartment, shedding the virus along the way. The measles virus usually infects the cells of the throat and lungs, but it can also survive in the air and linger on objects.

SIMON FENSTERSZAUB: You don't have to cough, you just have to breathe. It's the worst kind of contagion: it's airborne.

NARRATOR: Ninety percent of people who are exposed to the virus and don't have immunity get the disease. In this instance, two hours later, another unvaccinated person entered the same elevator. A week or so later he, too, became ill.

JANE ZUCKER: It was a very brief encounter, you know, seconds in an elevator! It just speaks to how infectious measles is. It will find those people who are unprotected in, in a community.

NARRATOR: In three months, more than 3,500 people were exposed to the measles virus in the Brooklyn area. Fifty-eight were infected, including two pregnant women. One miscarried. All were confirmed as unvaccinated at the time of infection.

JANE ZUCKER: Measles was declared eliminated back in 2000, and so this was the largest outbreak since elimination.

SIMON FENSTERSZAUB: It's like telling me "Look, we found smallpox!" Smallpox is eradicated. I mean no one sees measles. Who sees measles? Yeah, you'll see measles in third world countries, in other countries. This is New York. We don't see measles in New York!

NARRATOR: Around the world, pockets of low vaccination are appearing, often in affluent, mainstream communities. Anthropologist Heidi Larson, studies why people do, or don't, place trust in vaccines.

DR. HEIDI LARSON (London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine): There isn't just a world polarized between pro- and anti-vaccine populations. There's 80-plus percent in the middle who it's either just a social norm—it's good for our children and for our public health; others that are starting to question—and a certain amount of questioning is healthy; and then there's some that are starting to get more anxious and are vulnerable to tipping into becoming against vaccines, if they don't feel like they're getting the right information, or they are not being heard.

NARRATOR: Gabriella Makstman wants to vaccinate her two children, but she's chosen not to follow the recommended vaccine schedule.

GABRIELLA MAKSTMAN: So, the plan is to be fully vaccinated as soon as possible, but we're doing one vaccine at a time. I don't know if that's the right way.

YULIA PATSAY: I don't know where we came up with that.

GABRIELLA MAKSTMAN: Yeah, I don't know.

NARRATOR: Yulia Patsay has a four-year-old and is expecting another child soon. She delayed vaccinating her oldest 'til she was three.

YULIA PATSAY: I was concerned that her immune system couldn't handle it, and we just waited.

MARIANNA FASTOVSKY: My son and her, they're not vaccinated yet, and my older ones don't have boosters.

NARRATOR: Marianna Fastovsky has four children. She vaccinated at first, but then one child had a seizure.

MARIANNA FASTOVSKY: I'm just really worried, you know, about reactions. And I am worried about the diseases, so I'm kind of confused, really.

NARRATOR: In America, children must be vaccinated before they start kindergarten, but the required shots vary from state to state and most allow for exemptions based on personal or religious beliefs.

Here, in California, almost three percent of children are exempt, and in some schools it's more than 30 percent.

YULIA PATSAY: I have a lot of friends who don't vaccinate at all, and if you say "vaccine" around them, they look at you like you were literally, well, you know, like you were poisoning your child. On the other hand, you have parents that they can't even understand why this is even a question.

GABRIELLA MAKSTMAN: Nobody is willing to really have a conversation with you and discuss, "What's a severe reaction? Is it okay to have a seizure?" I would really like to know what the real risks are.

BRIAN ZIKMUND-FISHER: Is it okay question to vaccines? Of course it is. It's the start of a conversation that says this is something worthy of being concerned about.

NARRATOR: Decision scientist, Brian Zikmund-Fisher, studies how we think about risk. He's based at the University of Michigan where, in this hall, in 1955, the first polio vaccine was announced.

BRIAN ZIKMUND-FISHER: Fifty years ago, you asked any parent, any grandparent about polio, about measles, about pertussis and they knew cases. It was part of their daily existence. What's changed now is that we've done such a good job of vaccinating most, not all, most people in our community, that they are rare. "I have never seen it, so why should I be concerned about it?"

PAUL OFFIT: The history of vaccines is clear. If you start to decrease vaccine immunization rates, you start to see the diseases re-emerge. It's a history that we don't seem to learn from.

NARRATOR: Paul Offit is an infectious disease expert. He helped invent a vaccine to protect against rotavirus disease, which kills hundreds of thousands of children worldwide. As a pediatrician, he's witnessed, firsthand, children dying from preventable diseases.

PAUL OFFIT: I guess we all have our biases. Mine is that I work in a hospital, and so, for example, in 1991, in the city of Philadelphia, there was a massive measles epidemic. Of the nine children who died during that 1991 epidemic, seven of them died in our hospital. So we had to stand by and watch, while we tried to support them. And you know, as doctors, your, your job is to try and save children's lives, and when you stand helplessly by and watch them die it's…it just gets to you.

NARRATOR: Human history is scarred with stories of deadly germs destroying lives. Five-hundred years ago, about one in three children died before the age of five. But then, we began to fight back.

Surprisingly, vaccination evolved from a type of traditional medicine, at least 1,000 years ago. In India, when a wave of smallpox approached a town, there are tales of people doing something extraordinary, they lined up to actually buy the disease. Brahmin healers would take a cloth and rub the person's upper arm, then they would scratch the skin, just enough to draw blood. Finally, they would then apply dried smallpox scabs, taken from patients who had survived the disease. Most people would get sick but recover. From that point on they were protected.

Over one thousand years ago, these Brahmins had observed one of the basic principles of immunization, that you rarely get infected twice.

PAUL OFFIT: We've got to give people credit. I mean, they got it right. They knew that there was something going on, that, that protected you, they just had no idea what it was or why.

NARRATOR: Fast-forward around 700 years, to Europe, where over 400,000 people were dying from smallpox every year. An English mother, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, wrote of seeing Turkish women deliberately inoculating their children with smallpox, using a method similar to the Brahmins.

LADY MARY WORTLEY MONTAGU (From letters, Mutter Museum/Voiceover): The children play together all the rest of the day, then the fever begins to seize them, and they keep to their beds two days, very seldom three. And in eight days' time they are as well as before their illness.

NARRATOR: Lady Mary successfully inoculated her own son and introduced the technique to England. People didn't understand why it worked, and it was never risk-free, but the smallpox death rate dropped, from around 30 percent to two percent.

Seventy years later, an English doctor named Edward Jenner took the next vital step. He demonstrated that deliberate infection with a mild, non-fatal disease, called "cowpox," would protect against smallpox. He called his technique "vaccination," from "vacca," Latin for "cow."

PAUL OFFIT: Edward Jenner's observation caused us to eliminate a disease from the face of the earth, a disease that killed as many as 500-million people. Amazing, right?

NARRATOR: But as vaccination made smallpox disappear, a curious thing happened: stories began to circulate of the dangers of the vaccination itself.

PAUL OFFIT: Once Jenner's vaccine was used widely, not surprisingly, people became concerned, for the same reason that people are concerned today, which is that, that adults or children were being inoculated with a biological fluid they didn't understand.

They knew that it came from a cow, and that concerned them. And people, I think, were not sophisticated enough to know that a cowpox virus wouldn't make you become a cow, but that was their fear.

You could argue that the same fears are alive today.

BRIAN ZIKMUND-FISHER: Our lack of understanding of vaccines is something that would naturally evoke fear in us, but once we acknowledge that a vaccine, by its very nature, is going to make us afraid, then we have to ask the next question, which is, "Well, why should I be doing it?"

NARRATOR: To understand how vaccines work, we first need to understand immunity. Sir Gustav Nossal is a world renowned immunologist.

SIR GUSTAV NOSSAL (University of Melbourne): Immunity is a wonderful natural defense system of the human body. It depends on the white cells of the blood to rapidly, rapidly, rapidly get you protected against the disease.

NARRATOR: Imagine millions of immune cells, such as white blood cells, all on the lookout for specific germs. If they spot something foreign, like flu, they prepare to fight.

GUSTAV NOSSAL: When that flu bug enters your body, the white cells like to move in on it, and they get a bit angry.

NARRATOR: The immune cells arm themselves and then replicate, creating an army of clones. Then, launching powerful germ-seeking agents, called "antibodies," they tag the germs for disposal. Once the germ is removed, the immune army disbands, but they leave behind "memory cells." Their job is to remember the invader and to sound the alarm if it ever appears again.

GUSTAV NOSSAL: When we're born, we're not yet very mature in terms of our immune system. So, if an infection strikes a little infant, then there's a great vulnerability. It's the tiniest ones that need the most protection.

NARRATOR: The recommended vaccine schedule is designed to close this window of vulnerability.

GUSTAV NOSSAL: Some people believe that you don't need to vaccinate your child because you've got such a beautiful and good immune system. They forget that these bugs that surround us have been coevolving with us, sometimes for millions of years, and, in some respects, they're cleverer than us. They have worked out ways of evading the immune system unless you pre-arm it. So putting it bluntly, the white cells mightn't be fast enough or smart enough, if we hadn't whipped them along by a prior immunization.

NARRATOR: A vaccine, in effect, sends in an imposter: a weakened or dead part of the germ, just enough to be recognized. The immune cells mount the defense. Because the threat is low, they quickly disband, but the all-important memory cells have been created. The immune system is now prepared for the real germ. To arm our immune system against multiple germs, different vaccines can be combined. This reduces the number of shots we need and studies show it to be safe.

GUSTAV NOSSAL: What we have seen in the industrialized world is, essentially, all of the major epidemics, they've vanished. Mums today have every expectation that their beautiful little baby will live, and not be polished off by diphtheria, by tetanus, even, occasionally, by measles. Now, that is the transformation in young lives that vaccines have brought.

NARRATOR: Vaccines do more than protect individuals, they can protect entire communities. The 2013 measles outbreak in New York hit hard and fast, but remained within the Brooklyn area. Why didn't it spread to the other 8,000,000 people in the city? The virus was in circulation, even though it often wasn't obvious, and it was being carried by people who often had no idea they were infected, but the vast majority of people who came into contact with the virus had protection: they were vaccinated.

BRIAN ZIKMUND-FISHER: There's two things that matter for whether or not I'm going to get sick. One is if I bump into somebody who has the disease, am I protected against it or not?

But the other piece, and the more important piece, is the chance I will bump into somebody in the first place, who has this disease. And you can think of this as these sort of concentric circles of people. And the less the disease exists in my circle or the next circle or the next circle, the safer I am.

NARRATOR: It's known as "herd immunity," and it protects everyone, including young babies, and people who can't be vaccinated for medical reasons.

And in New York, it worked.

JANE ZUCKER: If we didn't have the high vaccination levels that we do, you know, in New York City and, and even in, in this community, I can promise you we would have had hundreds, if not thousands, of cases.

NARRATOR: But this protection is fragile. For highly infectious diseases like measles, we need 95 percent of the community vaccinated for herd immunity to hold. If the rate drops, even just a few percent, herd immunity can collapse. In France, when measles vaccination rates were around 89 percent the impact was dramatic.

In 2007, there were around 40 cases of measles across France. Then, in 2008, a 10-year-old girl returned from holiday in Austria. She went back to school and played with some friends. Several days later, the girls became ill. The measles infection spread from district to district, infecting the susceptible population. In 2011, there were almost 15,000 cases; at least six people died.

JANE ZUCKER: It's astounding to me that, in this day and age, that you can have people dying of measles in the developed world. So for people who say this doesn't happen anymore, we have the proof.

HEIDI LARSON: It's a combination of people's risk tolerance is low and yet they have a distorted notion of how invulnerable they are, that they would never get certain diseases and if they did, they'd be fine.

NARRATOR: Low vaccination rates can also be fuelled by mistrust and amplified by frightening stories.

BRIAN ZIKMUND-FISHER: The stories that circulate, go viral, are the stories that have that emotional power. And what's the most emotional story? The story of some child being hurt.

NARRATOR: Luke Philbin was born a healthy, normal baby. When he was six-months old, his mother took him for his scheduled vaccinations. Seventeen hours later Luke had a seizure.

SAM JACKSON (Luke Philbin's Mother): He went into this full violent convulsions—he was frothing at the mouth, he was, he was just completely shaking and—and then I … beside myself, I didn't know what to do. And I rang the ambulance, and just as they entered the house he just stopped and went completely lifeless and turned blue. They gave him some oxygen and they said, "We need to take him to hospital right now."

NARRATOR: The doctors explained the vaccine had caused a fever, which had triggered Luke's seizure.

TOM PHILBIN (Luke Philbin's Father): Ten days later and I got another call at work, from Sam, and he'd had another seizure. That was when it really sort of dawned on us, I think, that something really serious was going on.

NARRATOR: Luke's seizures continued, constantly.

SAM JACKSON: I went to the internet, and I was searching everywhere just to find similar stories.

TOM PHILBIN: For that six-month period, as far as we were concerned, it was vaccine-related. And we were blaming ourselves, up to that point, really. Why did we do this? Why did we do this? If we hadn't done this, he'd be fine.

NARRATOR: After many months of searching the world for answers, they discovered the clues to Luke's illness lay on the other side of Melbourne.

Ingrid Scheffer leads a team of Australian neuroscientists studying rare cases like Luke's, cases where prolonged seizures happen soon after vaccination.

INGRID SCHEFFER (Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health, University of Melbourne): Hello, Lukey. Awwww.

It's really important that it occurred so close to his vaccination. And this is really what led to the thinking that there was a "vaccine encephalopathy." And I say "so-called" [air quotations gesture] because everyone associated that the timing of the vaccination and the timing of the first seizure meant that the vaccine was causative.

You're a perfect boy.

NARRATOR: For six years, the team studied the patients carefully. They discovered that the histories and symptoms matched those of a rare form of epilepsy, called Dravet syndrome.

INGRID SCHEFFER: Dravet syndrome is a very severe epilepsy, beginning in infancy, and it occurs in a previously normal and well baby. And their development slowly slows down, so they'd have normal development, and then between one to two years of age, it sort of plateaus. And, by far, the majority of children with Dravet syndrome have intellectual disability.

NARRATOR: Dravet syndrome is caused by mutations in a particular gene, called SCN1A, which impact key pathways in the brain. These are usually new mutations, not something passed on from the child's parents.

In 2006, the team made a key discovery: the majority of the children who had prolonged seizures after vaccination, also had a mutation causing Dravet syndrome.

INGRID SCHEFFER: The gene, the SCN1A mutation, is the cause of the Dravet syndrome, and the vaccine is, at most, a trigger for a seizure. And anybody with epilepsy has triggers for their seizures. They're not causative, they're triggers. So, you can have genes causing your epilepsy, but triggers are commonly sleep deprivation, stress and, in this situation, vaccination is a trigger.

NARRATOR: When Luke was tested, they discovered he, too, had Dravet syndrome.

Today, Luke's parents know that any fever can trigger his seizures, whether from a toothache or from a vaccine. They also understand that Luke was going to get this condition anyway.

SAM JACKSON: We've chosen not to vaccinate further, because we know it was a trigger.

TOM PHILBIN: We rely on other people having their kids vaccinated to protect Luke.

NARRATOR: Luke's type of epilepsy is rare; you're more likely to be struck by lightning. Yet his story is an example of how a vaccine can appear to cause harm.

The majority of children have no side effects from a vaccine. Some may experience slight swelling at the injection site, or develop a fever, a normal immune response. Occasionally, children can have a seizure after a vaccine, but this is usually a brief, one-time event, with no damage.

But there are extremely rare cases, where a vaccine has done harm, cases like David Salamone's.

DAVID SALAMONE (Polio Patient): I contracted polio from the vaccination. It affected my right leg. My muscles atrophied. I wear a leg brace.

NARRATOR: In 1990, when David was six months old, his parents took him for his oral polio vaccine. Within 24 hours he had a fever and a rash.

JOHN SALAMONE (Father of Polio Patient): So we took him to the pediatrician, and he basically said, "Oh, it's, it's nothing. You know, I mean, just, yeah, probably a little reaction, but, don't worry about it."

KATHY SALAMONE (Mother of Polio Patient): …high fever.

JOHN SALAMONE: So, it just seemed to get worse. Suddenly we noticed that he wasn't even able to move his lower extremities.

NARRATOR: David's paralysis was eventually tracked back to the vaccine, and to a series of events that occurred over 50 years ago.

ARCHIVAL FOOTAGE: In the all-out fight against polio led by the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, there were many years of struggle and heartbreak…

NARRATOR: In the 1950s, tens of thousands of American children were paralyzed by polio, and thousands of them died. It was one of the most feared diseases of the 20th century.

Then, in 1955, came an announcement that changed history.

ARCHIVAL FOOTAGE: A major medical hurdle was crossed with the discovery, of Dr. Jonas Salk, of the anti-polio vaccine.

NARRATOR: Thanks to the injectable "Salk" vaccine and later, the oral "Sabin" vaccine, polio rates plummeted by 99 percent. The disease largely vanished from the U.S. But the oral polio vaccine carried a risk: there was a small chance that the weakened virus within it could mutate and actually cause polio, a risk of around one in 2.4-million doses.

JOHN SALAMONE (HOME VIDEO): Okay, David, come on down.

NARRATOR: By 1994, the only cases of polio in the U.S. were those caused by the oral vaccine itself.

JOHN SALAMONE (HOME VIDEO): I want to show you something.

We failed to ask the question, "Does it pass the risk/benefit ratio test?" And, obviously, if the only cases of polio you have in a country come from the very vaccine designed to prevent it, it doesn't pass. It shouldn't be given.

NARRATOR: David's father lobbied to have the vaccine changed, and in the year 2000, across the U.S., the oral vaccine was replaced by a safer injectable version.

JOHN SALAMONE: This vaccine had a problem, and there was a better one, and we fixed it. The system worked. Too many had to suffer, but the system worked.

DAVID SALAMONE: I'm not against vaccinations, I'm pro-vaccinations. We had thousands of people contracting polio prior to the vaccination. We came out with the vaccination, and that number decreased significantly, so less people are getting sick, less people are getting affected. And that's a good thing.

NARRATOR: Changing and adapting vaccines as new evidence emerges is a vital and ongoing process, but sometimes vaccines are blamed for causing harm, when there's no scientific proof.

Autism is one of the most baffling health issues of our generation. Around one in 70 children are diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder in the U.S., today. It's not a single disease, but rather a complex web of disorders marked by communication difficulties and repetitive behaviors. The question is, what causes it?

ALISON SINGER (Jodie's Mother): This beautiful girl is my daughter, Jodie. She's 16, and she has autism, and now she's in residential placement. And I'm here today, as I am every weekend, visiting her. It's the highlight of my week.

As a parent, I would love to have a better understanding of why she behaves the way she behaves, why we have go through the same rituals and routines, every single time. We need to understand, so that we can help her.

NARRATOR: Alison Singer channeled her need for answers, becoming an autism advocate, raising funds for research.

Alison noticed Jodie's symptoms around the same time as her daughter had her vaccinations, so she, like many parents, suspected there could be a link.

ALISON SINGER: Clearly, children were getting more vaccines than we had gotten when we were born, and more and more children were being diagnosed with autism. So I felt that, yes, this was an area that we needed to look at and see if there was a relationship between vaccines and autism.

NARRATOR: In 1998, an English doctor, Andrew Wakefield, argued there was a link between autism and MMR, the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine. His study of 12 children was published in a major medical journal, The Lancet.

ALISON SINGER: When I read that, I felt…I was taken aback. We have to look at this. Fortunately, those are studies that can be done.

NARRATOR: A search began, to see if the link between autism and the MMR vaccine could be confirmed. Scientists examined the medical records of hundreds of thousands of children. But study after study revealed that whether the children were vaccinated or not, the rates of autism were the same.

ALISON SINGER: No one could replicate Andrew Wakefield's findings. Eventually, that study was shown to be fraudulent, and it was withdrawn.

NARRATOR: Similar studies failed to find any link between autism and a mercury-based preservative, called thimerosal. Still other studies failed to find any link between autism and the number or timing of vaccines.

ALISON SINGER: So, at this point, it's not like we have one study, or two studies, or five studies. We have dozens of studies!

I think we were right to look at whether vaccines might be a cause of autism, but there comes a point where there is so much evidence, none of which shows any link between vaccines and autism, that you have to say, "Enough!"

NARRATOR: Today, scientists like Daniel Geschwind are making dramatic progress in finding the real causes of autism. The story that's emerging is written in our D.N.A.

DR. DAN GESCHWIND (University of California, Los Angeles, School of Medicine): It's really extraordinary. Identifying the genetic causes is really important, because it gives us an anchor, a place to start.

NARRATOR: We know autism can run in families, but it took a revolution in D.N.A. sequencing technology to allow scientists to compare thousands of genes in people with and without autism, and to pinpoint specific mutations. Some of these gene mutations are inherited, but many are new, as in Dravet syndrome. Many of these genes play a role in brain development and in the way brain cells communicate.

DAN GESCHWIND: That can give us enormous clues about the onset of autism, where it begins, how it begins, and hopefully how to treat it.

NARRATOR: Scientists are also investigating environmental factors, but genes are a major part of the story, and they've led scientists to an extraordinary new insight: that autism begins in the womb.

DAN GESCHWIND: The genetics are pointing to early developmental processes, somewhere between 10 and 24 weeks or so of gestation. We don't know everything that causes autism at this point, but all of the genetics is pointing to fetal origin.

NARRATOR: So, as autism reveals its secrets, it's increasingly clear that childhood vaccines cannot be the cause.

ALISON SINGER: So, whenever I look at her, I'm extremely happy. Who's a pretty girl?

JODIE SINGER: I'm a pretty girl. Want some pastas?

ALISON SINGER: We can make pasta.

NARRATOR: Just as the underlying causes of autism are being illuminated, there's another controversy brewing, this time, around a vaccine that prevents cancer.

RICK PERRY IN ARCHIVE: …cervical cancer is a horrible way to die.

HEIDI HARRIS IN ARCHIVE: …severe reactions, up to and including death, as a result.

MICHELLE BACHMAN IN ARCHIVE: …and she suffered from mental retardation thereafter.

MIKE PAPANTONIO IN ARCHIVE: Take my chances of dying from cancer…

ARCHIVE NARRATION: …vaccine protects against a sexually transmitted disease…

ARCHIVE NARRATION: …fear mongering, ignorance…

NARRATOR: The vaccine to protect against H.P.V., human papillomavirus, has generated an unusual amount of publicity and confusion. H.P.V. is the most common cancer-causing virus on Earth. Around 80 percent of Americans will catch it at some stage in their lives. For most, it's harmless, but for some it causes cancer.

Every year, over 25,000 H.P.V.-related cancers occur in the U.S. Many are cervical cancer, in females, or throat cancers, in males.

AMY MIDDLEMAN: So, people often say they wish they could prevent cancer. This vaccine prevents cancer. Who doesn't want that for their child?

NARRATOR: Amy Middleman is a mother of three. She's also an adolescent pediatrician, involved in assessing the safety and effectiveness of the H.P.V. vaccine. She vaccinated her children as soon as it became available.

AMY MIDDLEMAN: I'm a little confused by the drama around this vaccine. To me, this is a lifesaving vaccine. I can't imagine not giving it to my children. On the other hand, I think sometimes we expect parents to have all the data that we have as physicians, and it's not really fair. So, our job, as providers, is to make sure we separate the issues and bring forth the important ones that should be considered.

NARRATOR: The key is to vaccinate boys and girls before they're ever exposed to the virus. That is, before they become sexually active.

AMY MIDDLEMAN: It's recommended for every boy and girl at age 11 to 12. It's just like everything else, you want to get the vaccine before you have a risk of getting the disease, so that it protects you.

NARRATOR: Around 60-million doses of the H.P.V. vaccine have been given in the U.S. Like all vaccines, it's carefully monitored for safety. There have been claims of rare, serious reactions, even deaths. These have been carefully investigated.

AMY MIDDLEMAN: There are no serious adverse events associated with this vaccine in a causal way. This is one of the safest vaccines that we have to offer, and it prevents cancer.

NARRATOR: For some, the link between the H.P.V. vaccine and sex is a concern.

(Mother of Amy Middleman's Patient): I have reservations about the H.P.V. vaccine. It's for a sexually transmitted disease, and I believe in teaching abstinence and chastity and…

NARRATOR: Studies show that any intimate contact, perhaps even deep kissing, can spread the virus, and getting the vaccine does not mean people start having sex earlier.

AMY MIDDLEMAN: The sex part, the way in which you get the target disease is irrelevant. We don't talk about diphtheria and how you can get diphtheria before we give the Tdap vaccine. How they're getting exposed is irrelevant to the ability to prevent the disease.

(Mother of Amy Middleman's Patient): I want her to make the decision, when she gets of age.

AMY MIDDLEMAN: Again, you know how I feel. I strongly recommend it. I try to prevent diseases whenever I can. But we can definitely get you the flu vaccine today, and we will keep talking about the H.P.V. vaccine, if that's okay with you.

Patients come to us asking for reassurance about these decisions, and if they don't get strong reassurance, it's pretty easy to put it off until the next visit, or the next visit, or "I'll think about it maybe the next time."

We're not talking about a cold that's going to go away, this is cancer. And this is what we've been working for years are ways to prevent cancer.

NARRATOR: On the other side of Oklahoma City, one woman knows only too well the cost of not being able to prevent her daughter's cancer.

CAROLYN THOMPSON (Mother of cervical cancer victim): Jennifer was 37 years old, and she died from cervical cancer. She had cancer in her liver and her lungs and her right hip and her left femur. And so, she died of the effects of the cancer, which was spreading through her body.

If there was something I could have done to protect her, of course I would have. The idea, now, that, that parents can vaccinate their children, to prevent those cervical cancers...I just wish that that had been available to us, to have changed the course of Jennifer's life. It just makes me very, very sad.

AMY MIDDLEMAN: As a mother and as a pediatrician, I think one of the biggest fears that I have and have always had, is that one of my children will get sick and I can't do anything about it. Or, one of my patients will get sick and I can't do anything about it. And to be able to prevent that is such a gift.

NARRATOR: Vaccines deliver a remarkable but often invisible gift, protecting against diseases we may never see around us. Yet, for parents, it can be hard not to worry about potential risks.

BRIAN ZIKMUND-FISHER: All of our lives are surrounded by the risks of every day. I walk across the street, I could be hit by a car. We live with risk, because it's part of what we all face in terms of getting what we want. I want to come to the football game, I want to have a fun day with my family, and those benefits are worth putting myself at risk.

Many people worry about the risks of serious adverse events or side effects from vaccines. How risky is that, really?

NARRATOR: Like any medication, vaccines are not risk-free, but the risk of a severe side effect is extremely small: for a life-threatening event, like a severe allergic reaction, it's around one in a million, ten times the number of people in this stadium.

BRIAN ZIKMUND-FISHER: These kinds of serious reactions are really that rare.

NARRATOR: Yet parents may worry about side effects, even when they are rare.

BRIAN ZIKMUND-FISHER: What we think about is, "What's going to happen to my kid? What if my kid is the one kid who happens to have this happen to them?"

GUSTAV NOSSAL: One of the things we have to remember, in medicine, is that it's a balancing act. Really, everything is measuring risks versus benefits. This is true of vaccines as well. There are risks; there are benefits. The risks happen to be miniscule of serious side reactions, the benefits are enormous.

NARRATOR: Vaccines protect us individually, in case the person next to us is carrying a dangerous germ, and the higher the overall vaccination rate, the more protection for everyone.

BRIAN ZIKMUND-FISHER: In 1955, this is where Dr. Thomas Francis announced to the world the outcome of the polio vaccine trials. And he told the world that the vaccine was safe, effective and potent. I love having this conversation here, in this room, because what we really need to do is to get back into the mindset of the people who were sitting here in 1955.

They looked at the vaccine trials and said, "Is this a better choice, not a perfect choice, a better choice than what we face if we do not vaccinate?" Because the less often we vaccinate, the more our lives will be touched, perhaps slowly at first, but eventually more and more by diseases that we once thought were gone.

NARRATOR: Baby Osman spent 17 days in the hospital with whooping cough. No one knows who spread the deadly germ to him, only that he was one of the lucky ones. Now six months old, he's recovering well.

Across America and the world, outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases continue to be reported.

In Michigan and several other states, personal exemption rates have risen above five percent. Some states, like California, have passed laws making it more difficult for parents to opt out. Wherever they live, parents continue to weigh what's best for their children and health officials continue to worry about saving lives.

PAUL OFFIT: We're all in this together. We all inhabit this planet together. We all make decisions that affect not only us, but others. And I would like to believe that there is something in us that allows us to see it that way.

Broadcast Credits

Sonya Pemberton

Mark Atkin A.S.E.

Lauri Markowitz

Glen Nowak

Walter Orenstein

Malvina Martin

Roslyn Walker

Johnny Camillo

Anton Herbert

Paul Rusnak

James Shirvill

Michiko Smith

Collin Smith

Ashley Tindall

Supported by SBS/Film Victoria Traineeship Program

Julie Leask

Andrew Masterson

© 2014 Origin Music Publishing (APRA)

Music recorded and mixed by Robin Gist

Lucy Paplinska

Bibliothèque de L'Académie Nationale de Médecine

CDC/Mary Hilperthauser/Stafford Smith/Meredith Hickson/ Dr John Noble, Jr.

CNN

Critical Past

December Media / Pemberton Films

Eli Lilly

EUFA

Getty Images

Julian Harneis

L'Oreal Women in Science footage

Directed by Alexandre Auvigne, Courtesy of Phénomène, France

The Mutter Museum

NBC Universal

Staplegun

Prelinger Archives

Developed with the assistance of Film Victoria

© 2013 Genepool Productions, Screen Australia and SBS Corporation

The University of Oklahoma

The University of California

The University of Michigan

The Oregon Health & Science University Doernbecher Children's Hospital

The City of New York

Mayor's Office of Media and Entertainment

Grand Central Terminal

Oklahoma Film & Music Office

City of Philadelphia

Greater Philadelphia Film Office

Quality Health Center

San Francisco Recreation and Park Department

John Luker

Musikvergnuegen, Inc.

Rob Morsberger

Eddie Ward

A NOVA Production by Tangled Bank Studios, LLC in association with Genepool Productions Pty. Ltd. for WGBH Boston.

© MMXIV Tangled Bank Studios, LLC

All rights reserved

Tangled Bank Studios, LLC is a production company established and funded by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute

Additional Material © 2014 WGBH Educational Foundation

All rights reserved

This program was produced by WGBH, which is solely responsible for its content

IMAGE

- (children playing)

- © Peter Cade/Getty Images

Participants

- Dr. Daryl Efron

- Pediatrician, The Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne www.rch.org.au/ccch/media/Dr_Daryl_Efron/

- Marianna Fastovsky

- Dr. Simon Fensterszaub

- General Practitioner

- Dr. Dan Geschwind

- Autism Geneticist, University of California, Los Angeles School of Medicine people.healthsciences.ucla.edu/research/institution/personnel?personnel_id=8903

- Sam Jackson

- Dr. Heidi Larson

- Anthropologist, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine www.vaccineconfidence.org/people.html

- Gabriella Makstman

- Dr. Amy Middleman

- Adolescent Medicine Specialist, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center

- Sir Gustav Nossal

- Immunologist, The University of Melbourne www.sciencearchive.org.au/scientists/interviews/n/gn.html

- Dr. Paul Offit

- Infectious Disease Specialist, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia paul-offit.com/about/

- Yulia Patsay

- Tom Philbin

- David Salamone

- John Salamone

- Kathy Salamone

- Dr. Ingrid Scheffer

- Pediatric Neurologist, Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health www.ingridscheffer.com/

- Alison Singer

- Autism Science Foundation www.autismsciencefoundation.org/about/leadership/board-of-directors

- Carolyn Thompson

- Dr. Brian Zikmund-Fisher

- Decision Psychologist, University of Michigan www.sph.umich.edu/iscr/faculty/profile.cfm?uniqname=bzikmund

- Dr. Jane Zucker

- Infectious Disease Specialist, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene

Resources

Preview | 00:30

Full Program | 53:10

Full program available for streaming through

Watch Online

Full program available

Soon