Profile: Bonnie Bassler

- Posted 01.09.07

- NOVA scienceNOW

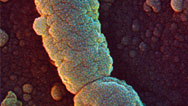

(This video is no longer available for streaming.) Bonnie Bassler has been called the "Bacteria Whisperer," and even if she doesn't speak directly to microbes, she is passionate about them. Until recently, no one thought bacteria communicated with one another and coordinated their behavior. But Bassler, a molecular biologist at Princeton, has discovered "quorum sensing." In some cases, when certain bacteria sense that they are in a large enough group (a quorum), they mobilize to attack a host, triggering disease. The implications for medical science are huge.

Transcript

PROFILE: BONNIE BASSLER

PBS Airdate: January 9, 2007

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Some people have a special way with other living things, They seem to understand them, even relate to them.

You've heard of horse whisperers and maybe even dog whisperers. Well, in this episode's profile, here's a scientist who is tuned in to some creatures I guarantee you have never talked to. In fact, you can't even see them.

She's been called the "Bacteria Whisperer."

But with a whisper is never how Bonnie Bassler starts her day. This MacArthur Fellow, and prestigious Howard Hughes Medical investigator, and member of the National Academy of Sciences, starts each weekday in aerobics class—as the teacher, of course.

BONNIE BASSLER (Princeton University): I have been teaching aerobics for 23 years, more than half of my life. And everybody thinks I'm so committed to this, and I'm so disciplined. And it's a big scam, because I would never go, if I wasn't the teacher.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: But Bonnie is a teacher to the core, in aerobics and in molecular biology at Princeton...

BONNIE BASSLER: Who wants to talk to me about science?

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: ...where she also wants to see some sweat.

BONNIE BASSLER: Five or ten minutes, get some science!

If you want me to do it for you...

STUDENT: Yeah?

BONNIE BASSLER: ...I won't because it wouldn't kill you to learn a little genetics.

Come on, you guys!

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: In fact, ask Bonnie about bacteria, and she just can't help teaching.

BONNIE BASSLER: Bacteria are single-celled organisms. Bacteria are the model organisms for everything that we know in higher organisms. There are 10 times more bacterial cells in you or on you than human cells.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Bonnie and her lab work on how bacteria talk to each other. That's right: bacteria talking. It's a process called quorum sensing, and Bonnie's lab has been leading the way in understanding exactly how it works.

NED WINGREEN (Princeton University): She's really the one who's shown that this is something, that this is something that all these bacteria are doing all the time. And if we want to understand them, we have to understand quorum sensing.

BONNIE BASSLER: So I grew up some bacteria for you to see, and I want to show you my favorite part, so you have to come with me into this room.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Bonnie has spent years studying vibrio harveyi, marine bacteria that are harmless to humans and, triggered by quorum sensing, glow in the dark. By themselves, or in small numbers, these bacteria don't glow. They wait until they've assembled a quorum, that is, as they divide and their numbers increase, they each release a signaling molecule.

BONNIE BASSLER: We call autoinducers but you can think of like hormones.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: That is made by a gene in each of the neighboring vibrio harveyi as a way of announcing, "Hey, I'm here, too."

BONNIE BASSLER: They have these detectors on their membranes that you can think of like little locks and keys. And the molecule goes in, and once they feel that, then they know there's neighbors around.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: And when enough of these little guys have gotten together to form a critical mass, they all light up at the same time.

BONNIE BASSLER: So now, if I turn the lights off in the room, you're going to see them make this beautiful bioluminescence.

NED WINGREEN: One bacteria isn't able to make an impact by itself, but if there are a lot of them, they can work together. So quorum sensing is the way that they know, "Are there enough of us to undertake one of these group activities?"

BONNIE BASSLER: It's incorrect to think of bacteria as these asocial, single cells. They are individual cells, but they act in communities, exactly the way people do.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Bonnie was doing her post-doctoral work, when she found the genes that allow for communication in vibrio harveyi. And scientists from around the world yawned, because Bonnie's discovery was only in this species of marine bacteria, and not in one that's dangerous to humans.

BONNIE BASSLER: There's these few bacteria that were models, e-coli and salmonella, and if you didn't work on the models, then you worked on a pathogen, something that was important for human health. And so this quorum sensing, which—we didn't even call it this back then, because it was in this luminous bacteria that doesn't even hurt a fish—it was never going to be relevant for understanding even bacteria or higher organisms.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: But Bonnie believed otherwise. She thought her bacteria could tell her more about how all bacteria communicate, so she applied for a job to continue her work in quorum sensing.

BONNIE BASSLER: Oh, I applied to a lot of places for a job. I don't know, 20 or 30 or 40. And I got two interviews and one job.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Yeah, but that one job was at Princeton University.

TOM SILHAVY (Princeton University): I was chair of the committee that hired Bonnie Bassler. I know people at other places...I don't want to name names, but one of them said, "Why did you hire her?"

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Let's just say she did okay by landing at Princeton, and Princeton's belief in Bonnie had a huge payoff: her lab eventually discovered a second molecule used by her luminescent bacteria to communicate. And this second molecule was nearly universal.

BONNIE BASSLER: We found it, originally, of course, in vibrio harveyi. But then we could show that hundreds of bacteria made and used this molecule and that it was in every bacterium anybody's heard about.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: That means that even dangerous bacteria communicate by quorum sensing. Deadly pathogens turn deadly the same way that Bonnie's bacteria turn on their light.

Bonnie showed that there were two types of molecules that bacteria use for communication, that bacteria are bilingual. One type of molecule is used for communicating within their own species, and the other type, discovered by Bonnie, is used to talk to every species around them.

BONNIE BASSLER: Bacteria live in unbelievable mixtures of hundreds or thousands of species. Like on your teeth. There are 600 species of bacteria on your teeth every morning. And so, in order to get these beautiful communities, where they're working together and doing all these things, they have to know who their neighbors are.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: And some of those neighbors are not friendly. Using the molecule found by Bonnie's lab, bacteria know if they're surrounded by friend or foe, or when it's safe to light up or attack. If they don't have superior numbers, they won't act. Sometimes they team up across species, but mostly, it's a tiny jungle out there.

BONNIE BASSLER: There's eavesdropping and free-riding and cheating. And one guy's out there making a molecule, and the guy next to him eats it so that the molecule disappears.

NED WINGREEN: My gosh, these bacteria talking to each other across species. And that's something that had really not been an accepted idea. This was sort of just a crazy idea.

TOM SILHAVY: What Bonnie did to show that different species of bacteria could talk to each other really changes the landscape. And when that was realized by the rest of the scientific community, Bonnie's career took off like a rocket.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: But Bonnie was not launched by a scientific family.

BONNIE BASSLER: We never talked about science. My mom was a stay-at-home mom, my dad was a businessman, and my brother's a businessman, and my sister's in politics, right? So we're just all over the map.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: She moved around a lot as a girl, but was always kept grounded by her mother.

BONNIE BASSLER: My mom was the linchpin of this family. And I remember her saying things to me like, "You know, when I went to college, you could be a teacher or a nurse. Those were your two choices, as a woman," she goes, "but Bonnie, you could be anything you want."

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Bonnie's mother died when Bonnie was just a junior in college.

BONNIE BASSLER: I remember her telling me, when she was sick, that she would take all the steps the same. So I think she got payoffs, even though she didn't get the ones that like, you know, the world sees as the payoffs. Because these are like very...they're tangible, acceptable things, you know? The MacArthur, the National Academy, Howard Hughes, those are things that you can write in a Christmas card, right? And she just would've written other things.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Big things like Bonnie marrying actor Todd Reichart; little things like mercilessly beating her husband and colleagues at board games. Biologist Eric Wieschaus won a Nobel prize, but this night, lost to Bonnie.

BONNIE BASSLER: Yeah!

TOM SILHAVY: I've taken enormous pride in what she's accomplished. I would argue that our committee just did one hell of a fantastic job.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: But as Bonnie sees it, her work has only just begun. Quorum sensing is helping to shape a path to new drugs. Antibiotics currently work by killing bacteria, and more and more bacteria have grown resistant to these drugs. By using quorum sensing, it may become possible to disrupt a pathogen's communication, to neutralize it. For the foreseeable future, that's where Bonnie and her team will be putting their sweat.

BONNIE BASSLER: I want to make a drug. I want the science to be more than imaginary, where I think, "We're learning these fundamental principles, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah." I think we are doing that, but I want to do something really practical. I want to actually, in my lifetime, help people.

Credits

Bonnie Bassler Profile

- Edited by

- Robe Imbriano

- Produced and Directed by

- Carla Denly & Robe Imbriano

NOVA scienceNOW

- Executive Producer

- Samuel Fine

- Executive Editor

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Senior Series Producer

- Vincent Liota

- Supervising Producer

- Stephen Sweigart

- Editorial Producer

- Julia Cort

- Development Producer

- Vinita Mehta

- Program Editor

- David Chmura

- Post Production Supervisor

- Win Rosenfeld

- Unit Manager

- Candace White

- Associate Producers

- Mica McCarthy

- John Pavlus

- Win Rosenfeld

- Anna Lee Strachan

- Production Secretary

- Fran Laks

- Animator

- Brian Edgerton

- Compositor

- Yunsik Noh

- Camera

- Edward Marritz

- Robert Hanna

- Anthony Forma

- Peter Bonilla

- Stephen McCarthy

- Sound Recordists

- Alex Sullivan

- Michael Karas

- Mark Mandler

- Steve Jones

- Rusty Duggan

- Audio Mix

- John Jenkins

- Colorist

- Jim Ferguson

- Animation

- Sputnik

- Vincent Liota

- Space elevator animation by Space Elevator Visualization Group

- Visual Effects Supervisors

- Alan Chan

- Lee Stringer

- Digital Artists

- Eki Halkka

- Michael Cliett

- Matt Zeyn

- Jeff Leroy

- Jackson Yuen

- Consultant

- Brad Edwards

- Additional Editing

- Patricia Stern

- Win Rosenfeld

- Music

- Rob Morsberger

- NOVA scienceNOW Series Animation

- Edgeworx

- Archival Material

- Philip Baird/AnthroArcheArt.org

- Robert Frerck/Odyssey Productions/Chicago

- Getty Images

- HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. (Arthur Clarke recording)

- NASA

- Longevity Study Participants

- Barbara Brody

- Irma Daniel

- Sylvia Goldberger

- Frances Horowitz

- Toby Kirsh

- Louis Levinson

- Arthur Stern

- Special Thanks

- Harry's Coffee Shop

- Mike Jorgenson/WPRB

- Jason Saunders

- Arthur C. Clarke

- Rohan de Silva/The Arthur C. Clarke Foundation

- Oak Ridge National Laboratory

- Ray Baughman

- University of Wollongong

- The Space Needle Corporation

- Wirefly X PRIZE Cup

- LiftPort, Inc.

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- is director of the Hayden Planetarium in the Rose Center for Earth and Space at the American Museum of Natural History.

- NOVA Series Graphics

- yU + co.

- NOVA Theme Music

- Walter Werzowa

- John Luker

- Musikvergnuegen, Inc.

- Additional NOVA Theme Music

- Ray Loring

- Post Production Online Editor

- Spencer Gentry

- Closed Captioning

- The Caption Center

- NOVA Administrator

- Ashley King

- Publicity

- Eileen Campion

- Anna Lowi

- Yumi Huh

- Lindsay de la Rigaudiere

- Researcher

- Gaia Remerowski

- Production Coordinator

- Linda Callahan

- Unit Manager

- Carla Raimer

- Paralegal

- Raphael Nemes

- Legal Counsel

- Susan Rosen Shishko

- Assistant Editor

- Alex Kreuter

- Associate Producer Post Production

- Patrick Carey

- Post Production Supervisor

- Regina O'Toole

- Post Production Editor

- Rebecca Nieto

- Post Production Manager

- Nathan Gunner

- Producers, Special Projects

- Susanne Simpson

- Lisa Mirowitz

- Coordinating Producer

- Laurie Cahalane

- Senior Science Editor

- Evan Hadingham

- Senior Series Producer

- Melanie Wallace

- Managing Director

- Alan Ritsko

- Senior Executive Producer

- Paula S. Apsell

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0229297. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

NOVA scienceNOW is a trademark of the WGBH Educational Foundation

NOVA scienceNOW is produced for WGBH/Boston by NOVA

© 2007 WGBH Educational Foundation

All rights reserved

- Image credit: (Bonnie Bassler) Courtesy American Society for Microbiology

Participants

- Bonnie Bassler

- Princeton University www.molbio2.princeton.edu/index.php?option=content&task=view&id=27

- Tom Silhavy

- Princeton University www.molbio1.princeton.edu/labs/silhavy/Tom.html

- Ned Wingreen

- Princeton University www.molbio2.princeton.edu/index.php?option=content&task=view&id=247

Related Links

-

Bonnie Bassler: Expert Q&A

Bonnie Bassler answers questions about bacteria, pursuing a career in biology, and more.

-

Hear From Bonnie Bassler

The microbiologist and mother of quorum sensing talks about bacteria, good and bad.

-

Bacteria Talk

Microbiologist Bonnie Bassler describes the 600 species of bacteria on your teeth, how they communicate, and more.

-

Profile: Sangeeta Bhatia

Intrigued by the idea of artificial organs, a biomedical engineer uses computer-chip technology to craft tiny livers.

-

The Secret Life of Erika Ebbel

A former beauty queen, biochemist Erika Ebbel, is now tackling Huntington's disease.