Dan Taylor knows the Blériot XI inside and out. As a pilot

and historian at Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome in Rhinebeck, New York, he

helped restore an original 1909 model to flyable condition and

serves as its official pilot during the Aerodrome's weekly air

shows. Below, Taylor guides you through a tour of this pioneering

aircraft, giving you a detailed view of its key systems and

aeronautical innovations.

Front view

Front view

|

|

|

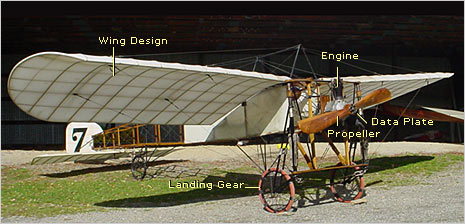

Large, paddle-like blades set at deep angles relative to each

other helped give the Blériot XI efficient thrust

despite its low-powered engine.

|

|

Propeller

The propeller on this plane is a typical design of the

period—a Chauvier-type style of propeller that was used

during that early period. These engines didn't turn up very

much. They were engines that maybe turned up 1,400 or 1,500

rpms, not like these big engines today that are turning up

real fast. A big, slow-turning prop was much more efficient.

The Wright brothers knew that, and their propellers were

turning very, very slowly but moving a lot of air. This is the

same thing with this engine, too. When I'm going down the

runway at maybe 30 miles per hour, it's only turning up about

1,800 rpms maximum.

|

Built by motorcycle engine designer Alessandro Anzani, this

engine was lightweight but provided just enough power to keep

the Blériot XI aloft.

|

|

Anzani Engine

Many of the early airplanes carried very lightweight

air-cooled engines. They wanted a lightweight engine because

they didn't really figure out all the structures yet as far as

the bracing of the airplane. You look at airplanes today and

everything is streamlined. They know about metals. Back in the

early days, they didn't. They were experimenting. Everything

was a new trial. This is a 30- or 35-horsepower Anzani engine.

Blériot flew the English Channel with only a

25-horsepower engine, but this was the next step up. It

powered the airplane pretty well but it was prone to

overheating with its cast-iron cylinders because you weren't

moving very quickly. You were probably doing only 35 or 40

miles per hour. Hold on to your hat! It was an airplane engine

that was very useful for this airplane before the rotary

engines came out. The radial air-cooled engine worked pretty

well in its day.

|

Since his light airplane was often thrown about by wind close

to the ground, Blériot designed landing gear that could

pivot, allowing his craft to turn slightly into the wind yet

keep rolling in the direction of the runway.

|

|

Main Landing Gear

Back in 1909-1910, these airplanes were feathers in the wind.

They had a problem with that. So what Blériot did was

make the landing gear pivot. It has what's called "castering

landing gear." As I take the airplane and I move it from side

to side, the landing gear actually pivots a little bit. And

the reason for that was so that the airplane could still land

at an angle and the wheels would track whatever direction you

were going. That's a feature that's still used today. Certain

bombers and airplanes actually have a castering gear that you

can dial in for a crosswind landing. Pretty remarkable:

technology from 1909.

|

This original data plate from 1909 shows the aircraft's

origins and factory information.

|

|

Data Plate

This example here [of the Blériot XI] is serial number

56 of about 900 that were made. This [plane] was found at a

junkyard in Laconia, New Hampshire and all the parts that were

there showed a data plate and the data plate said "Paris,

France. Serial number 56. Blériot Type XI." It is the

oldest flying airplane in the United States and to have the

opportunity to fly an airplane like this here at Old Rhinebeck

is a great honor.

|

With a low-powered engine, these deeply curved wings are

needed to provide lift during slow flight.

|

|

Wing Design

The wings on this airplane, if you look at them, you'll notice

that the structure has a big what we call in aviation terms

"undercamber." If you look at a jet today, it's almost like a

flat board out there. The reason for that is that you don't

require as much lift because you have a lot of speed, a lot of

propulsion. With this airplane Louis Blériot knew he

didn't have a lot of power, so he needed a lot of lift at slow

speeds. This airfoil gives a lot of lift at slow speeds but

has a very abrupt stall characteristic. In other words, if you

don't keep that wing flying, it doesn't mean the engine

stalls, it just means that the engine ceases to have lift. So

because of that, you have to make sure you always have speed

over those wings or it can drop a wing and you can prang it.

But, just the same, the wing design is very unique to

Blériot.

|

Side view

Side view

|

|

|

Used to control the lateral movement of the aircraft, this

feature is still found in contemporary designs.

|

|

Rudder

To steer the airplane—much like conventional airplanes

today—I have a rudder so I can make left turns and right

turns very simply by moving that stick and the rudder bar in

the cockpit. And this hasn't changed at all on this design.

This is pretty much the way it always was.

|

The elevator controls the pitch of the aircraft, allowing it

to climb or descend. Blériot was one of the first to

pair this with a rudder, creating a now-standard tail design.

|

|

Elevator

Moving the stick fore and aft has elevator control for pitch.

Pull back on the stick and up we go—and the other way

down. So, houses get smaller, and houses get bigger.

|

Despite its appearance, this feature only supports the tail

once the aircraft has stopped. Other versions of the Type XI

used bamboo skids instead of wheels.

|

|

Tail Wheel

This is the tail of the Blériot XI. There were several

designs. There was the wheel, like we have on this

Blériot XI. There was also another method of doing it

where it was bamboo cane that was bent around as a "tail

skid." And they used that too on some of the later

Blériots.

|

The body of the Type XI had to be both strong and lightweight,

so Blériot designed a system of wire cross-braces to

secure its wooden frame.

|

|

Frame

The construction of these airplanes—they're built a

little bit like a bridge. You can see that there are cross

wires that are tightening all these pieces together. All this

is held in compression and in the cross-brace it's giving you

the strength. Louis Blériot came up with his own style

of turnbuckles, and it's just a piece of stiff wire that runs

threaded between here and as you tighten these little nuts up

it would pull this wire tighter. And sometimes if you had a

hard landing or something you'd need to retighten them because

the wire would stretch. This was considered the Louis

Blériot style of a turnbuckle. Nobody else really

copied it. It was just a design very unique to Blériot

alone.

|

The Blériot XI uses wing warping, a flight control

system pioneered by the Wright brothers, to turn the aircraft

left and right.

|

|

Wing Warping

Okay, so for the wing warping, as I'm balancing the airplane I

can move the stick from side to side. That would warp the

wing, bending it almost like a bird, in order to bank the

airplane. When I'm flying the Blériot XI, in this

particular airplane I have very little power, so I have to be

very slow on the controls, be ready for any pitch change or

any attitude change that I have to correct right away.

Sometimes, if a wing goes down, moving the wing warp isn't

enough and I can actually physically shift my weight in the

seat, lean to one side, and very slowly that wing will come

back up again.

|

Cockpit view

Cockpit view

|

|

|

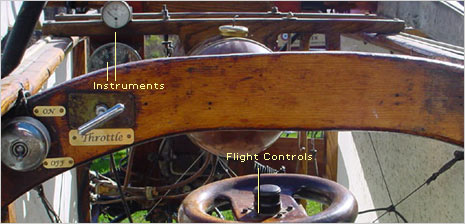

The Type XI features a single control stick and a set of foot

pedals to steer the aircraft, a configuration that remains

standard today.

|

|

Flight Controls

As you look at the cockpit you'll notice the control stick,

called the cloche, that bell-shaped housing that's named after

a lady's dress style of the period. The wheel on the top of

the control stick really doesn't turn or anything. It's just

something to hold on to. You can see the wires that are

attached just to the sides of that bell housing and those go

out to the control surfaces. They go to the elevators, to the

wing warp on the wings, and then you can see the rudder

bar—a wooden footrest almost—and that's what you

would use to operate the rudder. When I'm flying the

Blériot XI, in this particular airplane I have very

little power so I have to be not overly generous with the

control movement because you can get yourself into an awkward

attitude of the airplane where you may not be able to recover.

So everything in this airplane is done very slowly.

|

In 1909, aircraft cockpits had few if any flight instruments.

This Type XI features only two: an oil pressure gauge and a

tachometer.

|

|

Instruments

Blériots were used a great deal for the great circuit

races of Europe in 1911. And navigation was coming into its

own at that time, so they were learning about using maps and

using a compass and things like that. But in the early days

when they started out, instrumentation was very, very limited.

Usually it was just an oil pressure gauge, maybe an air speed

indicator, but for the most part it was just basic

instrumentation. Doing what I do when I fly this airplane is

flying what we call "by the seat of your pants." You really

just kind of feel how the airplane is that particular day when

you're taking off. Does it feel light? Can I pull back on the

stick? Oh, it's still going too slow: I have to lower the nose

a little bit. It's all done by feel.

|

|

|