|

Off and Running | Preparing for the Slides

Swiss Snow Science | Fire in the Hole

Switzerland

Monday Jan. 7, 1997

We leave for Switzerland at the end of a hectic day. Bob Poole, the

cinematographer, is having trouble getting out of Idaho. His first plane died

on the runway. We re-route him through Boston, and all end up on the same

flight except for sound recordist Dave Ruddick. We share a moment of relief

that we are safely on our way, but the peaceful feeling turns out to be

short-lived.

We leave for Switzerland at the end of a hectic day. Bob Poole, the

cinematographer, is having trouble getting out of Idaho. His first plane died

on the runway. We re-route him through Boston, and all end up on the same

flight except for sound recordist Dave Ruddick. We share a moment of relief

that we are safely on our way, but the peaceful feeling turns out to be

short-lived.

Tuesday Jan. 8, 1997

No one slept much on the plane. We arrive at 7am Swiss time, and it doesn't

take long to figure out that except for associate producer Kate Churchill and

myself, no one has any luggage. No film gear, no skis, no nothing. We have a

frustrating time trying to deal with the airline folks about what has

happened. They think they are business-like. I think they are impossible. We

are all tired and I am not only tired but grouchy. Film production is what we

are here for, and you can't get much done without gear.

By the time we give up and decide part of the team has to stay in Zurich to

wait for the gear, we realize we are now two hours late for our appointed

meeting with Dave Ruddick. We find him wandering forlornly, pushing two carts

of his gear, his hands bloody from getting them caught between the carts.

Assuming that we have completely forgotten him, Dave had asked a taxi driver

what it would cost to get to Davos. Unable to come up with the $1,000 fare,

Dave has been contemplating a long day pushing the carts around the airport.

The situation is so pathetic that there is nothing for us all to do but

dissolve into laughter.

When we collect ourselves, we decide that Dave, his gear, Jack McDonald (my

co-producer) and I will leave for Davos to meet with the scientists who think

we are showing up to film them. The rest of the team will get on the phone and

try to locate the lost gear.

Thursday Jan. 9

Rental plans are made for camera gear in case ours never turns up. Our talent

(another way of referring to the scientists we have come to film) are in

relatively good humor about the lost time. A call comes in from Dr. Tom Russi.

We are given a bonus day. The sequence we want to film on remote

weather sensing and snow stations has been postponed from Friday until

Saturday. The scientists will be working in a dramatic location, high up in the

mountains with a helicopter, and we are invited along to capture it on film.

The only problem is that our entire crew and gear have to make it to the

helicopter take-off location by the next morning, which seems unlikely. Then a

welcome message comes in from Kate back in Zurich. The gear is going to make

it. They will be in Davos tonight in time for a late dinner, equipment and

all.

Rental plans are made for camera gear in case ours never turns up. Our talent

(another way of referring to the scientists we have come to film) are in

relatively good humor about the lost time. A call comes in from Dr. Tom Russi.

We are given a bonus day. The sequence we want to film on remote

weather sensing and snow stations has been postponed from Friday until

Saturday. The scientists will be working in a dramatic location, high up in the

mountains with a helicopter, and we are invited along to capture it on film.

The only problem is that our entire crew and gear have to make it to the

helicopter take-off location by the next morning, which seems unlikely. Then a

welcome message comes in from Kate back in Zurich. The gear is going to make

it. They will be in Davos tonight in time for a late dinner, equipment and

all.

Friday Jan. 10

We start out at the Institute with Dr. Othmar Buser, who has worked

at the Institute's location on the top of a mountain—known as the

Weissfluhoch—for over 30 years. Over the last year, most of the

people from the Institute have moved to the new offices in town. But Othmar

won't move. He will be forced to retire next year, so he will keep doing what

he has been doing. It feels deserted and empty at the Weissfluhoch, but Dr.

Buser wins our hearts.

In a cold room, he runs a centrifuge to show us how the strength of the snow

can be measured; they take a homogeneous sample of snow and see how

much force it takes to break it. This reveals the strength of one single layer

of the snow, but it's only one small piece of the puzzle of figuring out the

forces that will cause an avalanche to let loose. It is easy to get lost in the

work, and we realize we are late for our meeting with Dr. Russi, who will drive

with us to the location for Saturday's helicopter shoot. We ski down, which is

faster than taking the funicular, and send our gear on the train. Gear. Now

that we have it, I continue to be surprised by how much of it there is. There

are five of us in two big vehicles, one so huge we have dubbed it the Milk

Truck.

In a cold room, he runs a centrifuge to show us how the strength of the snow

can be measured; they take a homogeneous sample of snow and see how

much force it takes to break it. This reveals the strength of one single layer

of the snow, but it's only one small piece of the puzzle of figuring out the

forces that will cause an avalanche to let loose. It is easy to get lost in the

work, and we realize we are late for our meeting with Dr. Russi, who will drive

with us to the location for Saturday's helicopter shoot. We ski down, which is

faster than taking the funicular, and send our gear on the train. Gear. Now

that we have it, I continue to be surprised by how much of it there is. There

are five of us in two big vehicles, one so huge we have dubbed it the Milk

Truck.

We follow Tom through the Alps on a wild ride through mountains and passes and

a road that clings to the side of a canyon somewhere on the Italian/Swiss

border. The smaller van is overheating. We add oil and water and keep going.

It is really beautiful. The sun sets somewhere in Italy in a town with a

stunning cathedral. Maybe our luck is changing.

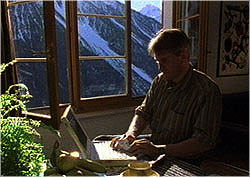

In a pub in Saas Grund Tom shows us how he can use his laptop computer and cell

phone to call directly to the snow and wind stations that he'll be working on

tomorrow, to download weather data. It is so cool! The technology gets everyone

pretty excited about the shoot. He shows us very graphically why we are

visiting one particular location. The data from a wind station above Simplon

Pass, a key route between Switzerland and Italy, isn't coming through. He needs

to find out what is wrong.

Saturday Jan. 11

What an incredible day! We share the price of the helicopter time with the

Swiss Institute folks and the local forecasters they are working with, and in

return are allowed to follow them all over the Valais region of Switzerland by

helicopter. It is a gorgeous day, really sunny, really calm—great

flying weather. And these are the big peaks. We fly low over glacial serac on

the way to the first location. Huge chunks of ice and deep crevasses are right

under us, and the Matterhorn looms in the distance. We are dropped at

the first site. Tom and his team take snow distribution measurements to

determine if this is a good location for one of their stations. We are high in

the Alps, moving around on skis, capturing science as it is happening on film,

and it is BEAUTIFUL.

What an incredible day! We share the price of the helicopter time with the

Swiss Institute folks and the local forecasters they are working with, and in

return are allowed to follow them all over the Valais region of Switzerland by

helicopter. It is a gorgeous day, really sunny, really calm—great

flying weather. And these are the big peaks. We fly low over glacial serac on

the way to the first location. Huge chunks of ice and deep crevasses are right

under us, and the Matterhorn looms in the distance. We are dropped at

the first site. Tom and his team take snow distribution measurements to

determine if this is a good location for one of their stations. We are high in

the Alps, moving around on skis, capturing science as it is happening on film,

and it is BEAUTIFUL.

Later in the day, we go to the stations above Simplon. At the snow

station Tom checks the accuracy of the data by taking manual measurements. He

points out the nearby wind station that he was unable to get data from last

night. It is just to the south, about 400 vertical feet above us at the top of

a sharp peak. The helicopter pilot can't land up there. The pilot will be able

to hover close to the ridge and the scientists will jump out. He doesn't want

to take the time or the risks of landing our crew up there, but agrees to take

Bob up and circle around as Tom goes up on the tower. It is a dramatic scene

from my vantage point; Tom climbing the tower, the helicopter with our camera

circling around, the late afternoon sun dropping behind the peaks and

backlighting the whole thing. At this point I can only hope the film will

capture the excitement of the scene in front of me.

Later in the day, we go to the stations above Simplon. At the snow

station Tom checks the accuracy of the data by taking manual measurements. He

points out the nearby wind station that he was unable to get data from last

night. It is just to the south, about 400 vertical feet above us at the top of

a sharp peak. The helicopter pilot can't land up there. The pilot will be able

to hover close to the ridge and the scientists will jump out. He doesn't want

to take the time or the risks of landing our crew up there, but agrees to take

Bob up and circle around as Tom goes up on the tower. It is a dramatic scene

from my vantage point; Tom climbing the tower, the helicopter with our camera

circling around, the late afternoon sun dropping behind the peaks and

backlighting the whole thing. At this point I can only hope the film will

capture the excitement of the scene in front of me.

Sunday Jan. 12

Despite a late night celebrating Dave's birthday and the long day of filming

yesterday, we are up early to head back to Davos. We stop and film the

avalanche protection structures called galleries that cover much of the roads

through Simplon Pass on the way.

Despite a late night celebrating Dave's birthday and the long day of filming

yesterday, we are up early to head back to Davos. We stop and film the

avalanche protection structures called galleries that cover much of the roads

through Simplon Pass on the way.

Monday Jan. 13

We head back up to the Institute at the Weissfluhoch to film an interview and

demonstrations with the ever-charming Dr. Buser. He is such a pleasure to work

with. And he confirms my observation from last year that avalanches don't make

much noise, despite how often we hear of them "thundering down the mountains."

When I ask the simple question about what an avalanche is, he says, "An

avalanche is just snow gliding down the slope. There are different forms how

they glide down—they might roll down, they might just glide and slip down.

But however it might let go and make a big cloud and then people say it is

thundering down. Well, I never heard one. However, people pretend there is a

noise."

We head back up to the Institute at the Weissfluhoch to film an interview and

demonstrations with the ever-charming Dr. Buser. He is such a pleasure to work

with. And he confirms my observation from last year that avalanches don't make

much noise, despite how often we hear of them "thundering down the mountains."

When I ask the simple question about what an avalanche is, he says, "An

avalanche is just snow gliding down the slope. There are different forms how

they glide down—they might roll down, they might just glide and slip down.

But however it might let go and make a big cloud and then people say it is

thundering down. Well, I never heard one. However, people pretend there is a

noise."

Tuesday Jan. 14

We accompany Dr. Buser first on the groomed terrain and then "off-piste" as he

skis home. We learn a lot about avalanches on the way. We find a path that has

recently run. We see snow that has fractured, but not avalanched. Instead it

has been slowly creeping downhill, leaving rolls and folds in the surface.

We are also reminded that although this is fun, and we are lucky to

be out here, it's not easy lugging hundreds of pounds of equipment along as we

ski down through some pretty crusty snow cover. One face plant with a big pack

on your back reminds you the hard way, literally.

We accompany Dr. Buser first on the groomed terrain and then "off-piste" as he

skis home. We learn a lot about avalanches on the way. We find a path that has

recently run. We see snow that has fractured, but not avalanched. Instead it

has been slowly creeping downhill, leaving rolls and folds in the surface.

We are also reminded that although this is fun, and we are lucky to

be out here, it's not easy lugging hundreds of pounds of equipment along as we

ski down through some pretty crusty snow cover. One face plant with a big pack

on your back reminds you the hard way, literally.

Wednesday Jan. 15

It's our last day in Switzerland, and we have decided to film a scene of Tom

Russi calling down the data from the stations, because we were so thrilled when

we saw it in the pub. We film at his house, which has a gorgeous view of the

mountains. Of course, as soon as we get it lit and are ready to roll, the sun

comes in the window directly behind him, and we have to relight the scene

completely. Dave Pickner is a master with lighting though, and we only lose

about 45 minutes.

It's our last day in Switzerland, and we have decided to film a scene of Tom

Russi calling down the data from the stations, because we were so thrilled when

we saw it in the pub. We film at his house, which has a gorgeous view of the

mountains. Of course, as soon as we get it lit and are ready to roll, the sun

comes in the window directly behind him, and we have to relight the scene

completely. Dave Pickner is a master with lighting though, and we only lose

about 45 minutes.

When we finish, we decide to use the remaining daylight to film general

Switzerland visuals on the way back to Zurich. We are staying in

Zurich tonight so we will be able to make early flights. I'm heading back to

the States, and the rest of the crew is heading to Iceland to meet the

co-producer Jack McDonald, who'll be directing the rest of the European shooting.

Saturday Jan. 18

Isafjordur , Iceland

It's near 11 a.m. and the sun has risen just enough to give us a glimpse of

dawn here in the West Fjords of Iceland, some 30 miles from the Arctic Circle.

The crew and I are on the tarmac of the Isafjordur airport, with camera and

sound ready, waiting to film the arrival of Magnus Mars Magnusson, Chief of the

Avalanche Division of the Icelandic Meteorological Office. If the weather

holds, we hope to film his inspection of the avalanche barrier going up above

the town of Flateyri nearby. The town was devastated by an avalanche a little

over a year ago.

Bad weather has kept the airport closed for two days. We made it in on the

first plane this morning from the capitol of Reykjavik. That was about 30

minutes ago. We've had to set up quickly. The airport staff has been very

helpful, and the control tower has just given us the signal that the plane

carrying Magnus is about to round the corner of the fjord. We begin to

roll film, as the plane emerges in the distance and begins to make a slow turn

our way in the pink dawn. Conditions appear perfect. With evening dusk

starting around 3 p.m. we're looking at a tight schedule. We can only hope the

weather will hold.

Bad weather has kept the airport closed for two days. We made it in on the

first plane this morning from the capitol of Reykjavik. That was about 30

minutes ago. We've had to set up quickly. The airport staff has been very

helpful, and the control tower has just given us the signal that the plane

carrying Magnus is about to round the corner of the fjord. We begin to

roll film, as the plane emerges in the distance and begins to make a slow turn

our way in the pink dawn. Conditions appear perfect. With evening dusk

starting around 3 p.m. we're looking at a tight schedule. We can only hope the

weather will hold.

Sunday Jan. 19

The weather is proving to be a moment to moment adventure. Yesterday's clear

skies have given way to a day of drizzling rain. With this overcast we have

even less daylight to work with. But we adjust and keep moving. What we've

planned to accomplish in one day will have to spread out over two. What's

hampering our filming, explains Magnus Mars Magnusson, are the same factors

that make avalanche forecasting particularly difficult here: capricious and

often vicious weather that can change dramatically from one minute to the next.

We're filming above the town of Flateyri as he says this, and just as he

finishes, the winds suddenly grow to gale force, water spouts begin to form in

the fjord below, and the temperature drops below zero.

The weather is proving to be a moment to moment adventure. Yesterday's clear

skies have given way to a day of drizzling rain. With this overcast we have

even less daylight to work with. But we adjust and keep moving. What we've

planned to accomplish in one day will have to spread out over two. What's

hampering our filming, explains Magnus Mars Magnusson, are the same factors

that make avalanche forecasting particularly difficult here: capricious and

often vicious weather that can change dramatically from one minute to the next.

We're filming above the town of Flateyri as he says this, and just as he

finishes, the winds suddenly grow to gale force, water spouts begin to form in

the fjord below, and the temperature drops below zero.

Monday Jan. 20

When you have too many lemons, they say, make lemonade. Thus we're making the

best of the weather here. Part of our shooting plan is to recreate the mood of

the evening when the avalanche fell. Since yesterday, the rain has turned into

snow, which is just fine for our purposes. We roam the town of Flateyri,

filming the townspeople as they go to and from work and the children at play in

the snow. Tonight we interview survivors of last year's avalanche. Tomorrow we

hope the wind will die down enough for a flight out, but our

meteorologist-in-residence, Magnus Mars Magnusson, isn't hopeful about our

chances.

Tuesday Jan. 21

Isafjordur

Before dawn, the crew and I head out on a long, cold drive to the other side of

the fjord, across from the town of Flateyri. There, in heavy winds, we hope to

film some distant views of the town—crucial shots that have so far eluded

us. We've attempted this before, but fog and passing storms have up to now

made a clear view impossible. This time, with the wind howling, and the snow

hitting us like sand, we clamber up a craggy slope and take position to await

the light.

Before dawn, the crew and I head out on a long, cold drive to the other side of

the fjord, across from the town of Flateyri. There, in heavy winds, we hope to

film some distant views of the town—crucial shots that have so far eluded

us. We've attempted this before, but fog and passing storms have up to now

made a clear view impossible. This time, with the wind howling, and the snow

hitting us like sand, we clamber up a craggy slope and take position to await

the light.

Keeping the camera still becomes an ordeal. When everything seems right, with

the sky starting to lighten and the town beginning to come into full view, we

spot a darker cloud massing at the end of the fjord, coming out of the Denmark

Strait. Ahead of it comes a blast of wind that starts to batter us on the hill.

It's hard to stand without leaning into its direction, and we're having serious

trouble keeping the camera in place. But for now we have no trouble seeing the

town, and we have the light we need, so Bob begins to roll. We get our shot,

and several others we hope will be helpful in edit. Now we have to get back to

Isafjordur as soon as possible to see if there is a morning flight out of the

West Fjords.

Back in Isafjordur, we discover our rush is for naught: no flight. For the

rest of the day, we bide our time, gathering periodically in the hotel restaurant

for news from the airport. Other guests, who've been hoping for days to get

back to Reykjavik, become familiar faces. They're more patient then we are.

Every hour we're told the winds still are not right. They're too strong and

coming from the wrong direction. A plane attempting a take-off in this

weather, we're told, would drop like a stone into the water, or slam into the

mountains as the aircraft struggled to get beyond the walls of the fjord.

Back in Isafjordur, we discover our rush is for naught: no flight. For the

rest of the day, we bide our time, gathering periodically in the hotel restaurant

for news from the airport. Other guests, who've been hoping for days to get

back to Reykjavik, become familiar faces. They're more patient then we are.

Every hour we're told the winds still are not right. They're too strong and

coming from the wrong direction. A plane attempting a take-off in this

weather, we're told, would drop like a stone into the water, or slam into the

mountains as the aircraft struggled to get beyond the walls of the fjord.

Wednesday Jan. 22

Reykjavik

This afternoon, the weather eased for only an hour or so, but it was enough

time to allow a couple of flights out of the West Fjords. Despite how remote

we felt, we arrived in the capital less than an hour later. From the airport,

we rushed into Reykjavik to set up for our final interview. Our subject was a

young woman whose house was destroyed by the avalanche. She was very

articulate and poignant as she told of the infamous night and early morning of

the avalanche. David Pickner's lighting appeared to be perfect, with all else

seeming to go well. With that interview completed, our shooting here in Iceland

is done. Everyone's tired. We understand we'll have no trouble leaving

tomorrow afternoon on our scheduled flight out of Iceland. For a change, the

weather is good.

Off and Running | Preparing for the Slides

Swiss Snow Science | Fire in the Hole

Photos: (1-2), (12-13) Kate Churchill/WGBH Educational Foundation; (3-11), WGBH.

Capturing |

Making |

Elements |

Snow Sense |

Resources

Mail |

Teacher's Guide |

Transcript |

Avalanche Home

|