|

|

|

by Peter Tyson July 2, 1998 Captain Drewry took the call at about 10 a.m. this morning. It was from the Coast Guard. A Canadian fishing boat about 40 miles south-southeast of the Thompson was in distress, with two crew aboard. The 56-foot boat was taking on water fast and had sent out a may-day. The Thompson and the John P. Tully, which had arrived at the Juan de Fuca research site last night, were the closest vessels in the area and immediately began steaming toward the fishing boat, whose position the Coast Guard had relayed to them. At 14 knots, it would take the Thompson about two and a half hours to cover the 40 miles, the captain told me. Then he kindly asked me to leave the bridge, since he was launching emergency procedures, including putting the ship's six-bed hospital at the ready. The winds had been gusting to 30 knots for 12 hours. The seas had come up to such a degree that by 9:30 last night, the ROPOS dive to cut the black smoker called "Phang" had to be terminated. Keith Shepherd and his ROPOS crew did not need to be reminded of the sudden storm that came up two years ago in this very spot on the Juan de Fuca Ridge. Within hours, 20-knot winds were gusting to 80 knots, and the waves were breaking over the A-frame on the fantail. In the midst of trying to get ROPOS back on board, the tether snapped and ROPOS vanished, never to be seen again. Debbie Kelley told me she was astonished that the only injury was a broken finger.

The Coast Guard had scrambled a spotter plane from Sacramento, California and a helicopter from Astoria, Oregon, and both were on-site as we drew near. Minus a few tens of feet on the wave sizes, the scene seemed straight out of the book The Perfect Storm, which I read not long before coming out here. The spotter plane was doing wide circles, with the stricken craft at its center. The orange-and-white helicopter swung low over the vessel, discussing the situation with the boat's captain over the radio. The fisherman reported that water was now beginning to flood the engine room. The helicopter then hovered low over the vessel, threw open its bay door, and dropped two gas-powered pumps onto the boat's stern deck. Our entire scientific party assembled on the Thompson's bow deck, along with the ship's six deckhands, who stood at the ready in case they were needed. Scoping the boat through binoculars while trying to keep my balance in the bow, I could see the small boat had taken a beating. Wave action had damaged the bow, probably causing the leak, and the main mast was bent well over to one side. But the boat still had power and was heading into the waves—a good sign.

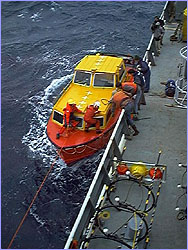

En route, the tender swung by the Thompson to drop off Vern Miller, an engineer with the University of Washington's Applied Physics Laboratory, whose expertise was needed on the Thompson to continue the research operations. I climbed up to 02 level and stood along the starboard rail, looking down on the tender as it cautiously approached the Thompson. Only then did I get a clear idea just how rough the seas were. The 26-foot tender bounced around like a toy boat in a bathtub. While Coast Guardsmen tightly gripped bow and stern lines, Miller carefully made his way to the bow and steadied himself, preparing to step onto the rope ladder the Thompson crew had dropped over the side. Deckhands leaned over the rail, ready to grab him when he started up. I looked up to see Captain Drewry standing at the bridge rail two levels above me. In the long minute before Miller finally went for the ladder, I glanced up at the captain two or three times. At the first glance he seemed to be standing casually, arms crossed, calmly assessing the situation; by the third, he appeared noticeably worried, leaning his weight on the rail, hand to his chin. Would he call off the attempt?

It was not over yet, however. The fishing boat suddenly appeared to lose power and began lolling broadside to the waves—a dangerous position. The Tully drew closer, and I watched as the tender pulled alongside the fishing boat two or three times. I wondered if the situation was becoming perilous enough that the fishermen would have to consider abandoning ship. I don't know the outcome, for just as I was pondering this a deckhand strode onto the bow where I'd been standing to tell me to withdraw: Captain Drewry had ordered full throttle to take us the 40 miles back to our research site, and the seas very well might start breaking over the bow. The Tully and the fishing boat were now on their own. Later in the empty mess hall I talked to the captain as he wolfed down the lunch he hadn't had time to eat earlier. He told me the fishermen were "profusely thankful" for our coming to their aid. They had been about to begin manual pumping when they saw our two ships on the horizon. "I'm just grateful nobody was injured," the captain said, then headed off without a word to the bridge. Peter Tyson is Online Producer of NOVA. The Tug of the Thompson (June 23) The ROPOS Guys (June 25) In the Juan de Fuca Strait (June 27) Special Report: A Visit To Atlantis (June 29) Dive 440 (July 1) Rescue at Sea (July 2) What's Your Position? (July 4) Phang! (July 5) 20,000 Pounds of Tension (July 8) Four for Four (July 11) Thrown Overboard (July 13) Was Grandma a Hyperthermophile? (July 15) Swing of the Yo-Yo (July 18) The Mission | Life in the Abyss | The Last Frontier | Dispatches E-mail | Resources | Table of Contents | Abyss Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated October 2000 |

Coast Guard tender ties up to Thompson.

Coast Guard tender ties up to Thompson.

Vern Miller (in white hat) makes his way to the

bow.

Vern Miller (in white hat) makes his way to the

bow.

Miller prepares to grab ladder, with deckhands at

the ready.

Miller prepares to grab ladder, with deckhands at

the ready.

The Thompson's zodiac is readied for launch, if

necessary.

The Thompson's zodiac is readied for launch, if

necessary.