Criminal Minds: Born or Made?

- Posted 10.17.12

- NOVA scienceNOW

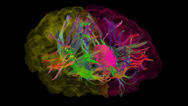

How might genes, brain structure, and environment conspire to make one person a violent criminal and another a rule-abiding citizen? We meet scientists who are using neuroimaging and genetic testing to uncover the biology of aggression—and explore the brain circuitry that could play a key role in the creation of a violent mind.

Transcript

Can Science Stop Crime?

PBS Airdate: October 17, 2012

DAVID POGUE: Is there any way science can stop crime?

I'm David Pogue, and on this episode of NOVA scienceNOW, we're tracking down cutting-edge research in the world of crime-fighting.

Are killers born or made?

JAMES FALLON (University of California, Irvine): These stories started to proliferate that there was something really wrong in our family.

DAVID POGUE: Are some people more prone to violence than others? What is the "warrior gene?" And what is its relationship to aggression?

KEVIN BEAVER (Florida State University): There are some men that are, biologically speaking, much more likely to be violent and aggressive than others.

DAVID POGUE: We're peering inside the criminal mind.

JOSHUA BUCKHOLTZ (Harvard University): Environments can change the way that your brain is wired.

DAVID POGUE: And…

Captain, there seems to be a disturbance in the tri delta vector.

With new technology, can we sense lies in the brain before they're even spoken?

JENNIFER VENDEMIA (University of South Carolina): In about 200 more milliseconds, he is going to be ready to lie.

DAVID POGUE: You got to the point where you could know whether I was lying or not?

JENNIFER VENDEMIA: Yes.

DAVID POGUE: That's freaky.

And can scientists help investigators determine when a victim died?

MICHELLE HAMILTON (Texas State University): So timing is really crucial.

DAVID POGUE: How do you even estimate?

PETER CUMMINGS (Commonwealth of Massachusetts Office of the Chief Medical Examiner): Come here. I'll show you.

DAVID POGUE: Isn't this usually reserved for less animated people?

PETER CUMMINGS: Typically.

DAVID POGUE: Their discoveries may shock you.

Three days? But how could that be?

MICHELLE HAMILTON: That's what we're going to try to find out.

DAVID POGUE: Can Science Stop Crime? Up next, on NOVA scienceNOW.

I'm David Pogue, host of NOVA scienceNOW by day, and by night a caped crusader on mission to fight crime. Okay, not really.

I had no idea that getting a perm was such a complex operation these days.

But I am on a mission to find out if science can stop crime.

Is this an eBay hair salon purchase, here?

But this isn't all fun and games. We hear about violence in the news all the time.

NEWS ANNOUNCER (Film Clip): In an especially brutal attack on a teenage…

NEWS ANNOUNCER (Film Clip): He confessed to killing 33 boys.

DAVID POGUE: Now, scientists are trying to find out if there is something different about the criminal mind.

JAMES FALLON: I looked at it, and I said "This is obviously a murderer." But it was me!

DAVID POGUE: Are violent brains created by nature...

There goes my spleen!

...or nurture?

EUGENE JACKSON: Faster, faster, faster. Power both hands, power both hands. Don't stop, don't stop, don't stop.

DAVID POGUE: I'm in San Francisco, learning how to fight. My trainer is a former gang member and mixed martial arts champion, Eugene "The Wolf" Jackson.

EUGENE JACKSON: Don't act like you was an A.P. student.

Good. We got the warm up out of the way.

DAVID POGUE: Jackson teaches teens to stay off the streets by taking their aggressions out in the ring. One of Jackson's most promising fighters is his own son: Nikko.

In the ring, Nikko is a feared fighter, the top of his division after only two years of training.

NIKKO JACKSON (Mixed Martial Arts Fighter): It's me versus you. Who's the better man? Like, only one of us is going to walk out with our hand raised, and I love that.

DAVID POGUE: Oh, my god, that's allowed? Cutting off his blood?

But as a young teen, Nikko's urge to fight got out of control.

NIKKO JACKSON: My first year of high school, I started straying down the wrong path.

DAVID POGUE: He got caught up with the notorious Taliban gang.

NEWS ANNOUNCER (Film Clip): Local, county, state and federal agencies teamed up to target these violent gang members they say are responsible for murders, assaults, rapes.

DAVID POGUE: We all know people who seem more violent than others, with shorter tempers and less self-control.

What causes aggressive behavior? Is it their upbringing? Is something wrong with their brains? And most controversial of all: could violence be in their genes?

There's obviously some aggression on display here.

KEVIN BEAVER: Right.

DAVID POGUE: Criminologist Kevin Beaver analyzed the genetic profiles of more than 1,000 young men and examined their criminal records and says he found a pattern.

KEVIN BEAVER: There are some men that are, biologically and genetically speaking, much more likely to be predisposed to be violent and aggressive than others.

DAVID POGUE: If that's true, is it possible that Nikko is one of them?

Nikko's D.N.A. has been analyzed, and he carries a controversial gene that, according to some reports, has been linked to violence.

It's been nicknamed the "warrior gene."

NIKKO JACKSON: I try to avoid problems as much as possible, but I have a limit, when reached, that I just flip out, redline a little bit.

DAVID POGUE: Is it really possible for one gene to have that kind of impact?

It turns out the so-called warrior gene is actually one version of a very important gene called "MAOA."

The gene works in the brain, helping to control chemicals called neurotransmitters that allow brain cells to communicate with each other.

KEVIN BEAVER: What that gene is responsible for doing is regulating levels of neurotransmitters. And these chemicals are responsible for our behaviors and our traits and things of that nature.

DAVID POGUE: All of us have the MAOA genes, but about a third of men carry a version that's less active and may leave more neurotransmitters floating around in our brains.

So, what's the result?

Well, we know what happens in mice.

Scientists at the University of Southern California engineered these mice to have a totally dysfunctional version of the gene, and their personalities are obviously transformed.

JOSHUA BUCKHOLTZ: When you do this in mice, you see that they become incredibly aggressive. These are the mice who are much more prone to biting and scratching and attacking.

Very straightforward, very simple test…

DAVID POGUE: But what happens in people?

Neuroscientist Joshua Buckholtz is one of the researchers now trying to unravel the relationship between this gene and violent behavior. He's found evidence that it can affect some key circuitry for emotion and learning in our brains.

JOSHUA BUCKHOLTZ: Let me tell you a story.

DAVID POGUE: To understand how this circuitry is supposed to work, Buckholtz told me a little story.

JOSHUA BUCKHOLTZ: Imagine that you're walking through the forest one day, and you look down and you see a snake.

DAVID POGUE: Snake, snaaaaake!

At that moment, a part of my brain that's primed to detect threats, called the amygdala, starts firing on all cylinders.

JOSHUA BUCKHOLTZ: The amygdala is like an alarm bell. It's really important for telling the rest of your body that something important is happening in the world, and you need to prepare for it. And your heart starts beating, and your pulse starts racing. You start sweating.

DAVID POGUE: But just as I'm starting to freak out, I take a closer look.

JOSHUA BUCKHOLTZ: And then you look down again, and you see that it's not a snake. It's actually a stick. And you feel your heart start calming down and your pulse isn't racing so much.

When you get some new information, you update.

DAVID POGUE: I'm able to update, because a learning part of my brain, in the prefrontal cortex, sends a message to my amygdala to shut off the alarm.

JOSHUA BUCKHOLTZ: And that sends input back down to the amygdala that says, "Cool it. Relax. We're okay." And you don't even feel anxious any more.

DAVID POGUE: At least, that's what's supposed to happen.

JOSHUA BUCKHOLTZ: Let's get you into the scanner.

DAVID POGUE: But when Buckholtz looked at the brains of people with the controversial version of MAOA, this part of the brain looked different.

JOSHUA BUCKHOLTZ: What we found was that the people show less grey matter in parts of the brain that are involved in this circuit we've been talking about.

DAVID POGUE: They have less grey matter?

JOSHUA BUCKHOLTZ: That's right. They have less grey matter than the people who have the, the other version of the gene.

DAVID POGUE: Not only did they have less grey matter, but when they were processing emotions, Buckholtz found their amygdalas were more active. So would that make them violent?

JOSHUA BUCKHOLTZ: Well, no, I mean this is the really interesting thing. All of these people who we brought into our lab are just normal community volunteers. These are not violent people. These are not psychopaths. These are not criminals.

And what that tells us is that that one single factor, acting alone, isn't enough to make someone violent.

DAVID POGUE: So even though about one third of men, including Nikko, have the so-called warrior gene, that doesn't make them aggressive.

The creation of a truly dangerous mind is far more mysterious than a single gene. D.N.A. is just one piece of the puzzle.

Oh, there goes my spleen.

So what are the other pieces? Few people have pondered this mystery more than neuroscientist James Fallon. Fallon has spent more than a decade studying the brains of violent killers, but a few years ago, his work took an unexpectedly personal turn, when he discovered that his own family has a lot of blood on its hands.

JAMES FALLON: These stories started to proliferate that there was something really wrong in our family.

DAVID POGUE: The Fallon clan includes nearly a dozen murderers, spanning more than three centuries. Suspected ax-killer Lizzie Borden was a cousin.

JAMES FALLON: That's not cheating its gamesmanning.

DAVID POGUE: Curious, Fallon had his immediate family tested for the so-called warrior gene, and it turns out that he, his mother, his wife and their son, James, all have it.

Next, Fallon investigated a collection of brain scans he'd gathered while working as a consultant on criminal trials. Compared to non-criminal brains, the murderers' scans appeared to show abnormal circuitry in the emotional part of the brain.

When Fallon had his own brain scanned, the result shocked him.

JAMES FALLON: I looked at it, and I said, "This is in the wrong pile; it's obviously a murderer." But it was me!

DAVID POGUE: Of course, it's actually impossible to I.D. a murderer based on a single scan, but Fallon saw a pattern of activity that suggested that he had the same unusual brain wiring as the criminals.

JAMES FALLON: It was disorienting, but it was like, "Oh, I got the joke; the joke is on me. I've been studying this stuff, and I got the pattern."

DAVID POGUE: Still, Fallon might be an aggressive Scrabble® player, but he is not violent. The question is, why not?

Fallon, himself, believes he was biologically at high-risk for a violent life, but that those negative factors were trumped by an overwhelmingly positive childhood.

JAMES FALLON: I was really loved—like a golden child—and it must have just negated the effect of all these other violence-related genes and everything.

DAVID POGUE: But could environment really counteract the negative effects of high-risk genes and brain structure? And what really goes on in a violent mind?

Scientists at Brookhaven National Laboratory are trying to answer just these kinds of questions, by investigating explosive, violent personalities, compared with calmer folks. And I've signed up to be one of their crash test dummies.

Do you have this in a 44-long?

Scientists here are doing comprehensive studies, on hundreds of volunteers.

300!

PATRICIA WOICIK (Brookhaven National Laboratory): Oh, sorry.

DAVID POGUE: Thanks a lot.

They run a battery of tests, analyzing personalities, genetics and family histories.

GENE-JACK WANG (Brookhaven National Laboratory): Before we start, can you hold my brain?

DAVID POGUE: They're trying to discover how these factors and our environment may impact aggression.

I get the third degree in a behavioral analysis called the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire.

PATRICIA WOICIK: What we're going to do is use a scale from one to five.

DAVID POGUE: That's a fancy name for asking really personal questions.

Okay.

PATRICIA WOICIK: People often joke about me when I'm not around?

DAVID POGUE: Two.

PATRICIA WOICIK: Sometimes I'm so envious…?

I typically don't agree with others…?

DAVID POGUE: One. Three.

PATRICIA WOICIK: I have no problems letting my friends know…?

Suddenly I get very mad, but it only lasts…

DAVID POGUE: One.

PATRICIA WOICIK: I often feel like a pressure cooker, pressure cooker, pressure cooker…

DAVID POGUE: Why do you people always ask me this?!

Luckily, my results show my aggression levels are normal.

But sifting through hundreds of profiles, lead investigator Nelly Alia-Klein looks for clues to what causes some people to have hair-trigger tempers.

Is there a scale? Is there a Richter scale for anger? Are there specific medical terms for these different degrees?

NELLY ALIA-KLEIN (Brookhaven National Laboratory): There are people who intermittently explode. They feel anger on a regular basis, and then, when there is a confluence of events that provoke them in certain ways, then they lose control, and they explode.

DAVID POGUE: Nelly Alia-Klein says this extreme form of anger that we sometimes see on the news is called "intermittent explosive disorder," or I.E.D. It's estimated to affect as many as 16 million Americans, and, incredibly, Alia-Klein can see how I.E.D. affects the brains of her test volunteers.

She uses PET scans, or Positron Emission Tomography, to measure activity levels in different parts of the brain.

With these scans she compares the average activity for two groups: people with high levels of aggression, including I.E.D., on the right, and those with low aggression on the left.

NELLY ALIA-KLEIN: We call these blobs. And what they tell us…

DAVID POGUE: That's the technical term?

NELLY ALIA-KLEIN: Yes.

DAVID POGUE: Blobs.

NELLY ALIA-KLEIN: And what they tell us is that's where the activity, the brain activity, is happening, in these specific regions of the brain.

DAVID POGUE: The more violent brains have big yellow blobs, showing increased activity in areas, including the premotor cortex, which helps control movement. This area often lights up when we're anxious and perceiving a threat, so we can get ready for action. What's surprising is that the brains of highly aggressive people appear raring to go, even when they are not doing anything.

NELLY ALIA-KLEIN: This is at rest. This is when nobody is bothering them, nobody is provoking them.

DAVID POGUE: Wait, so they have this much activity in their brain, at rest?

NELLY ALIA-KLEIN: Just at rest.

Their brain is more ready for action than the brains of these individuals, the non-aggressive ones.

DAVID POGUE: Well, no kidding. Their brains are going nuts, even when they're just lying there in a tube.

Alia-Klein's research reveals that people with intermittent explosive disorder may perceive threats, when there really are none.

So these folks with violent brains all have the so-called warrior gene? No! Once again, the gene and violence did not go hand in hand. So what else could be influencing these brains?

Some studies indicate that, in addition to genes, environmental factors, like an abusive childhood, can play a critical role in shaping the developing brain.

JOSHUA BUCKHOLTZ: One of the things that we know about environments is that environments, too, can change the way that your brain is wired, can change brain structure.

NELLY ALIA-KLEIN: The environment feeds the brain in such a way that it actually changes the brain.

DAVID POGUE: And one of the areas that can be changed by environment is the circuitry involving emotion.

JOSHUA BUCKHOLTZ: When you have multiple factors interacting, when you have genes that affect this brain circuit, when you have environmental influences that affect this circuit, but also thousands of other genes and thousands of other proteins in the human brain, those factors, together, are what push people over and, and are likely to cause them to be violent.

DAVID POGUE: There's also some encouraging news: evidence suggesting that a positive environment may help counteract negative risk factors.

NELLY ALIA-KLEIN: A positive environment can, sort of, change the picture, change the future, in a way.

DAVID POGUE: Research, so far, shows that it most often takes genetic and environmental factors to make a violent mind.

KEVIN BEAVER: What we see is that, in people with a certain genetic predisposition for violence or crime, that predisposition may never surface in the face of a positive environment that is able to dampen or mute the genetic effect.

DAVID POGUE: We can't control our genes, but environments can be changed, and that may make a difference.

Credits

CAN SCIENCE STOP CRIME?

- HOST

- David Pogue

- WRITTEN, PRODUCED AND DIRECTED BY

- Scott Tiffany

Tadayoshi Kohno Profile

- WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY

- Joshua Seftel

- PRODUCED BY

- Joshua Seftel & Erika Frankel

NOVA scienceNOW

- EXECUTIVE PRODUCER

- Julia Cort

- PRODUCTION MANAGER

- Stephanie Mills

- BUSINESS MANAGER

- Elizabeth Benjes

- INTERSTITIALS PRODUCED BY

- Brian Edgerton

- ORIGINAL MUSIC BY

- Christopher Rife

- SENIOR RESEARCHER

- Kate Becker

- CAN SCIENCE STOP CRIME? EDITED BY

- Brian Cassin

Steve Audette - PROFILE EDITED BY

- Marc Vives

- PRODUCTION MANAGER

- Maureen Lynch

- PROFILE PRODUCTION SUPERVISOR

- Jill Landaker Grunes

- ASSOCIATE PRODUCERS

- Mary Beth Griggs

Ben Sweeney

Catherine Bright - ARCHIVAL RESEARCH

- Minna Kane

Adam Talaid - RESEARCH

- Christopher O'Brien

Rachel Nuwer - CAMERA

- Jason Longo

Jeremiah Crowell

Ben McCoy

Mark Carroll

Paul Mailman - SOUND RECORDISTS

- Alex Altman

Mike Bellaccio

Steve Bonarrigo

Adriano Bravo

Steve Clack

Jason Pawlak - Scott Snyder

- Charles Tomaras

- ANIMATION BY

- Hero4Hire Creative, LLC

- ADDITIONAL MUSIC

- Scorekeeper's Music

- COLORIST

- Michael H. Amundson

- AUDIO MIX

- Heart Punch Studio, Inc.

- ADDITIONAL EDITING

- Rob Tinworth

Jean Dunoyer - ADDITIONAL CAMERA

- Zach Kuperstein

Jess Bichler

Ian Blair

A.J. Marson

Victoria Resendez

Oren Soffer

Alfonso Solis - MEDIA MANAGER

- Andrew Clark

- ASSISTANT EDITORS

- Rob Chapman

Steve Benjamin

Ben Sweeney - PRODUCTION ASSISTANTS

- Lee Stevens

Siena Brown

Nicole Beaudopin

Rebecca Brinson

Lauren Love

Matt Mohebalian

Gavin Murray

Stephanie Santos - POST PRODUCTION ASSISTANT

- Olaf Steel

- ARCHIVAL MATERIAL

- Pond5

Marcus R. Donner

Framepool

Shutterstock Images LLC

Dr. Arthur W. Toga, Laboratory of Neuro Imaging at UCLA

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, Harry Rhoads

-------

Mice footage courtesy "A Tale of Two MAO Genes" (2010),

produced by Prof. Jean Chen Shih and Prof. Marsha Kinder,

University of Southern California

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

Data Visualization by Arction Ltd.

- SPECIAL THANKS

- Academy for Scientific Investigative Training

Tim Acosta

Brookhaven National Laboratory

-------

Cold Springs Harbor Laboratory

ECS Elite Combat Sports

Evergreen Speedway/High Road Promotions

Joshua Buckholtz

Adele Testani

HurryDate

Forensic Anthropology Center at Texas State

Clark Freshman

Rex Jung, Ph.D, Department of Neurosurgery, University of New Mexico

Minakami Karate

-------

Hank Levy

David Matsumoto

Derek Mitchell

Jeff Moss

Stephen Porter

Rocktagon MMA

Rogue Empire Gym

Saloon NYC

University of Washington

Vanderbilt University Law School

Michael Warren - ADVISORS

- Sangeeta Bhatia

Charles Jennings

Richard Lifton

Neil Shubin

Rudy Tanzi - NOVA SERIES GRAPHICS

- yU + co.

- NOVA THEME MUSIC

- Walter Werzowa

John Luker

Musikvergnuegen, Inc. - ADDITIONAL NOVA THEME MUSIC

- Ray Loring

Rob Morsberger - POST PRODUCTION ONLINE EDITOR

- Spencer Gentry

- CLOSED CAPTIONING

- The Caption Center

- MARKETING AND PUBLICITY

- Karen Laverty

- PUBLICITY

- Eileen Campion

Victoria Louie - NOVA ADMINISTRATOR

- Kristen Sommerhalter

- PRODUCTION COORDINATOR

- Linda Callahan

- PARALEGAL

- Sarah Erlandson

- TALENT RELATIONS

- Scott Kardel, Esq.

Janice Flood - LEGAL COUNSEL

- Susan Rosen

- DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION

- Rachel Connolly

- DIGITAL PROJECTS MANAGER

- Kristine Allington

- DIRECTOR OF NEW MEDIA

- Lauren Aguirre

- ASSOCIATE PRODUCER

POST PRODUCTION - Patrick Carey

- POST PRODUCTION EDITOR

- Rebecca Nieto

- POST PRODUCTION MANAGER

- Nathan Gunner

- COMPLIANCE MANAGER

- Linzy Emery

- DEVELOPMENT PRODUCERS

- Pamela Rosenstein

David Condon - COORDINATING PRODUCER

- Laurie Cahalane

- SENIOR SCIENCE EDITOR

- Evan Hadingham

- SENIOR PRODUCER

- Chris Schmidt

- SENIOR SERIES PRODUCER

- Melanie Wallace

- MANAGING DIRECTOR

- Alan Ritsko

- SENIOR EXECUTIVE PRODUCER

- Paula S. Apsell

A Time Frame Films Production for NOVA

NOVA scienceNOW is a trademark of the WGBH Educational Foundation

NOVA scienceNOW is produced for WGBH/Boston

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0917517. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

© 2012 WGBH Educational Foundation

All rights reserved

Image credit:

- (handcuffs)

- © Greg Vote/Tetra Images/Corbis

Participants

- Nelly Alia-Klein

- Brookhaven National Laboratory

- Kevin M. Beaver

- Florida State University

- Joshua W. Buckholtz

- Harvard University

- James Fallon

- University of California, Irvine

- Nikko Jackson

- Mixed Martial Arts Fighter

Related Links

-

Can Science Stop Crime?

Explore the genetics behind criminal minds, the latest in lie detection, a human corpse "farm," and more.

-

Neuroscience in the Courts

As our understanding of the human brain grows more sophisticated, it is changing how courts determine culpability.

-

Neuroprediction and Crime

How much can brain imaging and genetic studies help in the fight against criminal behavior?

-

Secrets of Lie Detection

Scientists are learning how to spot lies at their very source: inside the brain.