"If we give young girls or anyone else a sense of purpose for what they are doing," says Yoky Matsuoka, "they will become more interested in doing it well." Matsuoka regularly welcomes young people to her Neurobotics Lab to learn about robotics. She hopes that they will be inspired to openly embrace the fields of math and science as she eventually did.

Matsuoka (center, drinking from bowl) takes part in a traditional Japanese tea ceremony during Hinamatsuri, or Girls' Day, a celebration of young girls.

Life in Japan can be difficult for a young woman who wants to be bold and stand out from the crowd. But rather than being stifled, Matsuoka channeled her energies through tennis.

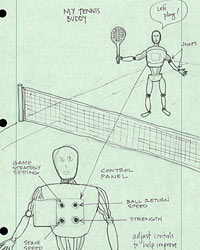

Despite suffering broken bones and torn tendons on the tennis court, Matsuoka dreamed of designing a robot that would push her harder than her human partners could. (Click the image above to see three diagrams of her imagined robot that the budding roboticist drew.)

No longer a self-described "airhead" and now an MIT graduate, Matsuoka stands alongside her mentor and advisor, robotics "bad boy" Rod Brooks. |

Robotics pioneer, prosthetics visionary, and 2007 recipient of a MacArthur "genius" grant, Japanese-born Yoky Matsuoka used to describe herself as an "airhead." Now she is a leading researcher in neurobotics, an emerging field that combines neuroscience with building robots. Her lab at the University of Washington in Seattle is working to develop advanced artificial hands and other body parts that will one day use signals directly from the brain to enhance the motor skills of individuals who have suffered amputation, spinal cord damage, and other traumatic injuries. In the following interview, learn more about Matsuoka's work, her life, and how she finally came to embrace her talents as a scientist. Hand craftQ: What is the "anatomically correct" robotic hand? Yoky Matsuoka: It's an advanced prosthetic that, once finished, will seem identical to a human hand. It will look like one, move like one, and it will even be controlled by the brain like a real hand. The prototype we're working on in my lab is different from every other prosthetic that's ever been built. It's made of bone-shaped structures and has tiny motors that act as muscles and threads that work like tendons. There are 30 motors in all, which will be controlled by the same neurosignals that are sent to our real muscles. It's really cool because in the process of building this hand, we're learning a lot about how the brain works. Q: How can the brain be used to control a machine? Matsuoka: When our brains tell our real hands to move, it feels very natural, and it's not something we're always conscious of. In order to replicate this behavior with robotic technology, we will first need to understand how brain signals work and then design our prosthetic hand to read these commands and express them fluidly. The signals will travel from the brain through the arm muscles and into wires leading to the hand. This process is known as "neurobotics" or "neuro robotics," which is a fairly new scientific field. Q: You've mentioned before that some people think neurobotics sounds a little like science fiction. How do you feel about that? Matsuoka: Well, I think it's a good point because the technology isn't fully here yet. Although some preliminary work has been done in the field, it could be 30 years before a patient gets to use a prosthetic hand as realistic as what we're trying to create in my lab. But I like the science-fiction comparison because it lets me relate to people. Whenever someone asks me what I do, it's easy to describe Star Wars and say "Remember the scene where Luke gets a new hand and it looks and moves like a real hand, except there's a little door on his arm that reveals mechanical parts moving around? That's what I'm making." This gives people an immediate understanding of my research. It's amusing to me because I began work on this hand before I ever saw Star Wars. Courting roboticsQ: What first got you interested in robotics? Matsuoka: Growing up in Japan, I played a lot of tennis. I've always been very competitive in everything I've done, so I started obsessing over it, pushing myself beyond my physical limits from about age 13. But to really do well at a sport like this, I realized I needed a partner with just the right skill set to test me where I needed improvement. As I got older, I fantasized about creating a robotic tennis partner that I could customize to challenge me in all the necessary ways. I thought it would be great to be able to program different players for different days depending on what I needed to work on. Later on, when I was in graduate school at MIT, my adviser had several of us build a humanoid robot called Cog, which students are continuing to work on today. Different body parts were up for grabs, so I volunteered to work on the hands. I felt that as a tennis player I could benefit from learning more about how our hands and arms function, although the robot I dreamed of building is still a long way away. Q: Even without a tennis robot, you managed to make the qualifying rounds for Wimbledon, which is no small feat. What made you stop playing competitively? Matsuoka: Well, one reason was that even though I strived to be the best, I never had the mindset of "I'm going to make it" that a lot of people have. It was more like I was on a highway where the other cars were going to a location called "Professional Tennis Career" and I didn't consider getting off at that exit. The other issue was that I got injured a lot. I was waking up at 6:30, going to school, then going to tennis camp two hours away, doing my homework while taking the train to the camp, and then getting home at 10:30 at night without having eaten dinner. But the mental toughness it took to do this wasn't enough because my body wasn't built to take it. I broke my ankle three times, I snapped my Achilles tendon, I hurt my back. I had a pretty severe injury almost every year so I finally had to stop obsessing and focus on other things. Q: Why did you push yourself so hard? Matsuoka: I wanted to stand out. When I was little, my parents were big fans of John McEnroe, who was a legendary tennis player. Whenever they would cheer for him I would think to myself, "Oh, he's supposed to be really cool; I'm supposed to like him." And I did like him because he was different from other people. He didn't care what anyone else thought of him, yet he was popular. In Japan, being young and being a girl made it very hard to be bold in the John McEnroe way. It wasn't acceptable for me to express my opinions, so I admired people who could do that with pride. I still tried to stand out, but only in ways that I thought would be acceptable. Since it was okay for me to be competitive in tennis, that's what I worked hard at. Rise and fall of an airheadQ: Did your obsession with success translate to other parts of your life? Matsuoka: It did in a lot of ways. For example, after I moved to the States when I was 16, I realized that acting smart or talented in school gave my classmates the wrong impression of me. It made me sound like a geek or nerd, and I really didn't want to be labeled those things. So I remodeled myself as an airhead. It turned out that when I acted dumb, I got to have more popular friends. But I was also secretly very good at math and science, and I never sacrificed that. Instead, I lied to my friends about which classes I was taking. In college at Berkeley I declared proudly that I didn't buy any textbooks, and I worked hard to show that I never studied. But then I would have to hide in the library days before each test and do nothing but study. I wanted to be popular without compromising the quality of what I was learning. It was very difficult—I was living a double life. Q: You're obviously not an airhead today. When did things change? Matsuoka: It didn't happen until I was a second-year graduate student. My classmates and I had to welcome the incoming students and try to entice them into doing the kinds of research we were working on. We all wore nametags and I thought it would be cool if I wrote "Airhead" on mine instead of "Yoky." But as I walked around campus that day, I could tell by the looks on people's faces that they didn't find this funny. Around that time, my adviser Rod Brooks pulled me aside and said "Look, Yoky. Stop acting like an airhead. It's not going to take you far." That was the first time I realized that pretending to be dumb wasn't the best idea in the world. I was at a first-class school doing really great research under a talented mentor. This double life was only going to hold me back. Q: You've accomplished a lot since that day. What was it like winning the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship? Matsuoka: There's a funny story that goes along with this. I got the call about the award while I was feeding my then eight-day-old baby. The guy on the phone said "I'm about to tell you something surprising so if you're holding anything fragile like a baby, please put it down." I said, "I do have a baby, but I can't put him down right now because he's nursing." The caller started laughing. He apparently always used this line as a joke, so that I was actually holding a baby was unexpected. But when he told me, it was a true honor. The MacArthur Fellowship is also known as the "genius award," so it's about as prestigious as can be, except for maybe the Nobel Prize and a few others. It was definitely not something I ever thought I would receive. Q: What drives you to succeed today? Matsuoka: I've realized now that I only have one lifetime to do the best that I can do, just like my role models have done. I've been given a chance to make a difference in society—to change the world—and I can't pretend to be an airhead or anything else that I'm not because it will only hold me back. I build hands because I want everyone to have a chance to experience their full human capability. Hands are what set us apart from other species. We built this society because we have dexterity and can use tools. Role modelingQ: Tell me about your role models. Matsuoka: They have always been people who weren't afraid to challenge conventional ideas. Everyone used to call John McEnroe the "bad boy of tennis," and similarly many people consider Rod Brooks the "bad boy of robotics." Rod thinks wild ideas that other people don't think of and won't accept, and he pushes for those ideas because he doesn't see a limit to what man can do. My role models are people with a lot of attitude. I think that because of this, my work has a lot of attitude. No one has tried to build prosthetics to be as realistic as what I'm making, and I like that my work is very different. Q: Do you consider yourself a role model? Matsuoka: I hope that I am. I believe that society will only advance if people learn from the previous generations and then try to become better than them. I want to be a role model for young scientists and for my children so that they can see what I strived for and change the world more than I have. The MacArthur Fellowship was never about money to me. People focus on the prize and ask, "Well, what are you going to use this money on?" It's not about that, but rather about the attention I can now bring to neurobotics and the opportunity I have to encourage more women to enter into the sciences. I want to continue the work people have done to make it more socially acceptable for young girls to pursue their dreams. Q: Do you think women in particular have to push themselves like you did in order to succeed in science? Matsuoka: I think that currently in the fields of science and engineering, women have to be pretty tough just to be taken seriously. They have to be very competitive, manage their time extremely well, and be the type of people that constantly push themselves to the limit. I feel that one reason I pushed myself so hard growing up and in school was because I wanted to prove myself not only as Yoky, but as a woman. Q: How would you make it easier for girls to pursue math and science? Matsuoka: What I really would like to do, starting at kindergarten and going through high school, is to change the image of math and science. I would like to show them the big picture, that these fields can be used to help people, because I think everyone can relate to that. I think "cool" in

high school is whatever you do that gains you acceptance. It's the

acceptance that comes from listening to the right kind of music, having the

right kind of hairstyle, wearing the right kind of makeup, and so on. I would

like for people to eventually think that the more science you do, the cooler

you are by the high-school definition. If we give young girls or anyone else a

sense of purpose for what they are doing, they will become more interested in

doing it well.

|

||||||||||

|

Interview conducted on January 27, 2008, at the Neurobotics Laboratory at the University of Washington's Paul G. Allen Center for Computer Science & Engineering by Josh Seftel, producer for NOVA scienceNOW, and edited by Rima Chaddha, assistant editor of NOVA online |

|||||||||||

|

© | Created July 2008 |

|||||||||||