Biggest Machine Ever Built

- By Susan K. Lewis

- Posted 07.01.07

- NOVA scienceNOW

When the Large Hadron Collider goes online in 2008, it will be largest and most expensive machine ever created. But why build an $8 billion behemoth to search for the smallest particles in the universe? NOVA scienceNOW host Neil deGrasse Tyson has given the question some thought.

Listen

Listen

Why build an $8 billion machine to seek the universe's smallest particles? Hear Neil Tyson's take in this podcast.

Transcript

Biggest Machine Ever Built

Posted: July 1, 2007

SUSAN LEWIS: You're listening to a NOVA scienceNOW podcast.

Far beneath the French and Swiss Alps, the biggest machine in the world is nearly complete. It's a technological marvel at the physics lab known as CERN. It might seem baffling: Why make an $8 billion behemoth to search for the smallest particles in the universe? Neil deGrasse Tyson has given it some thought.

NEIL deGRASSE TYSON: All this effort, all the physicists, all the money, all the fanfare that's surrounding the construction and the opening of CERN is all because we are standing at this precipice, looking out into an unexplored regime of physics, and any time you do that, there's something there to be discovered, history tells us.

CERN is creating a particle accelerator that's not only the biggest machine ever built. Why? Because they're creating the largest concentration of energy that has ever been produced. They're smashing high-speed protons together, breaking them into smaller particles than themselves, and when you do this, you will see particles you've never seen before, that you might have theorized about but don't show up in ordinary particle accelerators. You need the one that's at the cutting edge to discover it.

SUSAN LEWIS: For all you skeptics who might not care about sub-atomic particles, consider how other experiments at the frontier of physics have panned out.

NEIL deGRASSE TYSON: Any time you move a frontier of science, particularly a frontier of physics, and you look at the results that people publish, you say, "What? Is that related to anything?" And, you know, seven people in the world understand the result, and you look at it and you wonder why did you fund the project to begin with?

Well, such was the case with Michael Faraday in the 19th century where he played around with wires and magnetic fields, and he saw that an electric current moved through a wire when the wire moved through a magnetic field. And so he had a little meter that jumped every time he did this. This was, like, this was a curiosity. And he showed it to people: "Oh, that's nice," you know? "Is dinner ready yet?" People – no one really knew what this meant.

And that is the entire means by which we now generate electricity in modern times. It is the foundations of our modern electrical culture. And so it's possible for a result to be earlier than what is an obvious application for it, but if you always passed judgment on the frontier of research based on whether, at that moment, you could think of how to use it, then you are undermining the entire way by which society has progressed in our science and technological abilities.

SUSAN LEWIS: Even if it never leads to practical applications, Tyson thinks the work at CERN reflects an essential part of what it means to be human.

NEIL deGRASSE TYSON: I think we have the capacity to wonder, and the capacity to wonder is what drives scientists on all the respective frontiers that they work on. And they bring to the rest of the population a sense that we are still explorers. Explorers! That exploration today is happening in particle accelerators, and to deny our species that privilege is to take away so much of what, I think, defines us as human beings.

Credits

Audio

- Produced by

- Susan K. Lewis

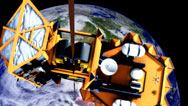

Image

- (collider)

- Courtesy David Sington/DOX Productions

Related Links

-

CERN

Go beneath the Alps to explore the biggest particle accelerator in the world, the Large Hadron Collider.

-

CERN: Expert Q&A

MIT particle physicist Peter Fisher answers questions about the Large Hadron Collider and other subatomic matters.

-

Space Elevator

Can we build a 22,000-mile-high cable to transport cargo and people into space?

-

Space Elevator: Expert Q&A

Physicist Brad Edwards answers questions about the space elevator.

You need the Flash Player plug-in to view this content.