|

|

|

|

Brain-Mapping Pioneers

What would you do if you were a doctor and had patients who

were missing pieces of their skulls? If you were Eduard

Hitzig, a German doctor working at a military hospital in

the 1860s, you'd conduct some experiments. Hitzig, working

on patients who had pieces of their skulls blown away in

battle, stimulated exposed brains with wires connected to a

battery. By doing so, he discovered that weak electric

shocks, when applied to areas at the back of the brain,

caused the patients' eyes to move.

|

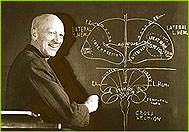

Wilder Penfield, a pioneering brain surgeon, mapped

the motor cortex using mild electric current.

Wilder Penfield, a pioneering brain surgeon, mapped

the motor cortex using mild electric current.

|

Later, around 1870, Hitzig teamed up with another doctor,

Gustav Fritsch. Setting up a makeshift lab in Fritsch's

house, the two stimulated the brains of live dogs. They

found that not only could they cause crude movements of the

dogs' bodies, but that specific areas of the brain

controlled specific movements.

John Hughlings Jackson, an English scientist, soon after

took the work of Fritsch and Hitzig even further. Based on

his observations of his wife's epileptic seizures, Jackson

came up with a more detailed theory of how the brain

controls muscles. He knew that every one of her seizures

followed the same pattern: It would start at one of her

hands, move to her wrist, then her shoulder, then her face.

It would finally affect the leg on the same side of her

body, then stop.

Jackson believed that the seizures were electrical

discharges within the brain. The discharges started at one

point and radiated out from that point. This suggested that

the brain was divided into different sections, and that each

section controlled the motor function (or movement) of a

different part of the body. And since the pattern never

varied, the way the brain is organized must also be set.

A brain exposed during surgery.

A brain exposed during surgery.

|

|

Wilder Penfield took the next exploratory voyage into the

brain starting in the 1940s. While operating on epileptic

patients, Penfield applied electric currents to the surface

of patients' brains in order to find problem areas. Since

the patients were awake during the operations, they could

tell Penfield what they were experiencing. Probing some

areas triggered whole memory sequences. For one patient,

Penfield triggered a familiar song that sounded so clear,

the patient thought it was being played in the operating

room.

During these operations, Penfield watched for any movement

of the patients' bodies. From this information, he was able

to map the motor cortex, the very part of the brain you can

map in this feature's activity.

Probe the Brain

|

A Map of the Motor Cortex

Photos: (1) Princeton University Press; (2) Courtesy of

John Postlethwait.

Visual Mind Games

|

From Ramachandran's Notebook

|

The Electric Brain

|

Probe the Brain

Resources

|

Teacher's Guide

|

Transcript

|

Site Map

|

Secrets of the Mind Home

Search |

Site Map

|

Previously Featured

|

Schedule

|

Feedback |

Teachers |

Shop

Join Us/E-Mail

| About NOVA |

Editor's Picks

|

Watch NOVAs online

|

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

©

| Updated October 2001

|

|

|

|