|

|

|

Part 2 | Back to Part 1 Eye sore The prickly pear's spines not only attack the skin but the eyes. "These minute hairs, when detached from the ripened fruit, are borne along on the South wind," wrote one early visitor to the island, "and if sufficient numbers enter the eye, the terrible irritation which they occasion gives rise to a species of blindness." A type of euphorbia, a spiny-desert succulent, can cause actual blindness. Another friend was lying on a tarp gazing up at the forest canopy when a drop of the milky-white latex from a euphorbia dripped into his eye, which soon turned bright red and swelled like a toad after the rains. Without a word, one of our guides slipped into the forest and returned with the stem of euphorbia that looked exactly like the one growing over our camp but which he assured us bore the antidote. With my friend's hesitant permission, the guide dripped some of that plant's milky-white latex into his eye. By the next morning, his eye was back to normal. Most unsettling is when a leech gets into your eye. A herpetologist who has had the pleasure three times told me about the first time it happened, in a remote rainforest in the middle of the night. "It went round to the back and started feeding," he said. "Oddly enough, I couldn't tell if it was feeding on the eyeball or on the eye socket." He ran to the nearest village, where an old woman, making sense of the meaning behind his frantic gestures, poured a mixture of salt and water into his eye, forcing the leech out. "That," he told me with the ghost of a smile on his lips, "would make most people a little bit twitchy, don't you think?" A natural death For the most part the aforementioned are mere annoyances, but there are other things in Madagascar that can make you twitch your last. The most notorious is the so-called man-eating tree of Madagascar. The first European description of this bulbous tree, a kind of elephantine Venus flytrap, appeared in the South Australian Register of 1881. In horrifying detail, the author tells how he watched aghast as members of the Mkodo tribe offered a woman in sacrifice to the dreaded tree, whose white, transparent leaves reminded him of the quivering mouthparts of an insect: The slender delicate palpi, with the fury of starved serpents, quivered a moment over her head, then as if instinct with demoniac intelligence fastened upon her in sudden coils round and round her neck and arms; then while her awful screams and yet more awful laughter rose wildly to be instantly strangled down again into a gurgling moan, the tendrils one after another, like great green serpents, with brutal energy and infernal rapidity, rose, retracted themselves, and wrapped her about in fold after fold, ever tightening with cruel swiftness and savage tenacity of anacondas fastening upon their prey. Never fear. Despite decades of speculation, which included the 1924 book Madagascar, Land of the Man-Eating Tree, no one has ever again laid eyes on this carnivorous horror, nor on the Mkodo tribe for that matter, and today most consider the story a fabrication, if a gruesomely good one.

You're not likely to accidentally swallow the tangena nut, but the same cannot be said for the tsingala, a poisonous black water beetle that typically kills cattle that swallow it within 24 hours. A 19th-century missionary who was traveling through the forest in a palanquin, a litter-on-poles that was the chief conveyance for foreigners in those days, described a tsingala attack on one of his carriers, who minutes before had slaked his thirst from a dirty pool: He stood stretching out both his arms and throwing back his head in a most frantic manner, at the same time shrieking most hideously. My first thoughts were speedily seconded by the words of his companions, who said: "He has swallowed a tsingala." Of course, I immediately got out of my palanquin and went back to the poor fellow. He was now lying on the ground and writhing in agony. His abdomen had become very swollen, and his skin very hot, and I felt that unless something could be done, and that speedily, the man must die. The man survived after a villager gave him an antidote made from leaves of certain plants steeped in water, but the missionary reported that it was several weeks before the man was strong enough to carry the palanquin again.

As if all these natural horrors were not enough to cope with, the visitor to remote areas of Madagascar has to be aware of one final, potentially lethal threat: the Malagasy villager. The Malagasy are among the friendliest, most peace-loving people I've ever met, but sadly, in the hinterlands many Malagasy harbor a bizarre belief that white foreigners are mpakafo, or "heart-stealers," who have come to Madagascar to kill Malagasy and eat their vital organs. One clue to the origin of this strange belief comes from the writings of the English missionary E. O. McMahon. In an 1892 article about the slave trade, which only ended when the French colonized the island three years later, McMahon recalled: One African who is now free told us how, when the dhow they were on was becalmed near the Madagascar coast and [a European] man-of-war boat was in chase, the Arabs called up the strongest of the slaves to row the dhow, and to make them work harder told them that those in pursuit were cannibals, and were only chasing them to catch them for food.... Whatever the origin, the belief in heart-stealers is widespread in rural areas of Madagascar; one researcher told me its prevalence is 100 percent in certain regions. That same researcher recounted the time a couple that he accidentally surprised while they were farming on a remote hillside backed away from him in terror, shovels raised in defense. It's not unusual to have grown men drop everything and flee, he told me, and some time ago two French geologists were killed when villagers took them for heart-stealers. So what's to fear in the Malagasy forest? Lots. Peter Tyson is online producer of NOVA and author of The Eighth Continent: Life, Death, and Discovery in the Lost World of Madagascar (William Morrow, 2000). Photos: (1,2) Jacinth O'Donnell/Survival Anglia Ltd.; (4) Peter Tyson; (6) Survival Anglia Ltd. The Expedition | Surviving The Wilds | Explore Madagascar Dispatches | Classroom Resources | E-Mail | Resources Site Map | The Wilds of Madagascar Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

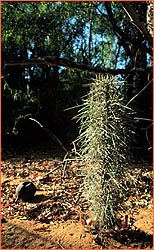

You have to watch your eyes while traveling through the spiny desert—and not just because of innumerable spines. Sap from some succulents can blind you.

You have to watch your eyes while traveling through the spiny desert—and not just because of innumerable spines. Sap from some succulents can blind you.

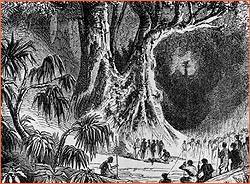

A suspect undergoes the tangena "trial by ordeal" in a Malagasy wood.

A suspect undergoes the tangena "trial by ordeal" in a Malagasy wood. In remote regions, Malagasy have been known to drop everything and flee from white-skinned foreigners, for fear that they might be "heart-stealers."

In remote regions, Malagasy have been known to drop everything and flee from white-skinned foreigners, for fear that they might be "heart-stealers."