|

|

|

by Peter Tyson In the summer of 1996, I joined Fordham University paleoecologist David Burney and his 17-member team on an expedition to Anjohibe ("Big Cave"), a cavern in Madagascar's far west. In the caves, we planned to search for remains of the island's "megafauna": giant lemurs, elephant birds, pygmy hippos, and other creatures weighing over 25 pounds, all of which save one mysteriously went extinct sometime in the past 2,000 years. But first we had to get there. After driving all day alongside the Betsiboka, a broad, chocolate-colored river once bristling with crocodiles, we stopped for the night at a forestry station, where I had a brush with the sole surviving member of the Malagasy megafauna—the Nile crocodile. After 14 hours on the road, crammed into the trucks like telephone-booth-stuffers, we're eager to stretch our legs, and Burney offers to lead us along the road to a nearby lake to look for crocs. The road is empty and dark, and the stars are magnificent. With my headlamp, I immediately start picking out chameleons sleeping in roadside shrubs and trees. On the way, Burney primes us with croc stories. At almost every lake where he has worked in Madagascar, he says, villagers have told him that somebody was recently killed there by a crocodile. So common is this tragedy that when all hope is lost in life, the Malagasy say "Got into the clutches of the crocodile." While coring lakebed sediments on a raft, Burney himself has had some close encounters. His depth finder has symbols for fish of different sizes, and every now and then the largest symbol will light up. "Sometimes you'll see this big 'fish' swim up right under the boat and stay there," he told me. "It's kind of an uneasy feeling." He tells us about his doctoral advisor at Duke, who was doing research with a graduate student on a lake in Africa. A crocodile took a bite out of their inflatable boat, sinking it. They had to swim two miles to shore. The next morning, they thought of heading out to retrieve the outboard, which lay in about seven feet of water, but so many crocs lay on the beach that they thought better of it.

"Peter, get back! I see eyeshine." I don't see it myself, but I don't need any convincing. I am up that embankment so fast my sneakers leave skidmarks. Burney's stories have worked me up, and I've read many tales of encounters with these dangerous beasts. One of the earliest accounts, written in the 1670s by a French traveler named Sieur Du Bois, describes a trial by crocodile: The natives also swear by the crocodile, which they name Voa, with which the Rivers and Lakes of this Island are full; saying that they wish to be eaten by them, if they have done that of which they are accus'd; this done, they are oblig'd to pass thru a river, which they do. It also happens often that in passing through the water, they are taken and eaten by these Crocodiles or Voa. The spectators of this fine proof of truth say that such an one has done the thing of which he was accus'd, 'tis wherefore he has been eaten.

Europeans of the last century who journeyed along the Betsiboka had no such fanciful notions about what one of them dubbed "crawling saw-backed monsters." They knew the crocodile's natural history (see The Clickable Croc), and they rightly feared it more than any other wild animal in Madagascar. [The island does harbor other dangerous creatures—see A Forest Full of Frights.] Their apprehension wafts from early accounts like a dank odor. "I never saw such a dreadful snapping apparatus in my life; a shark's mouth looks innocent by comparison," Grainge wrote after shooting a "small" one of eight feet, nine inches. Another traveler, grounded overnight on a sandbar that "one could almost cross on the backs of its crocodiles," sat all night on the forward deck, his Springfield across his knees, "ready to drive 150 grains of steel-jacketed lead between one of those encircling pairs of eyes which glowed at us so malevolently from the darkness." Their numbers could be astounding. After spying about 40 crocodiles sleeping on a sand spit, another traveler on the Betsiboka began counting. In the first hour, he counted 105; in the next half hour, 102. He estimates that in four days he and his party saw no less than 1,600 crocodiles.

Peter Tyson is Online Producer of NOVA. This article was excerpted from Tyson's book The Eighth Continent: Life, Death, and Discovery in the Lost World of Madagascar (William Morrow, 2000), with permission of HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. Photos: (1) Jacinth O'Donnell/Survival Anglia Ltd.; (4) Toby Hough/Survival Anglia Ltd. The Expedition | Surviving The Wilds | Explore Madagascar Dispatches | Classroom Resources | E-Mail | Resources Site Map | The Wilds of Madagascar Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

The Nile crocodile, object of abject fear throughout Madagascar.

The Nile crocodile, object of abject fear throughout Madagascar.

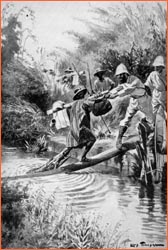

In this early watercolor, a French explorer shoots at a crocodile about to attack a Malagasy in mid-stream.

In this early watercolor, a French explorer shoots at a crocodile about to attack a Malagasy in mid-stream. In the 19th century, when this watercolor was painted, surprise attacks by crocodiles were all too common.

In the 19th century, when this watercolor was painted, surprise attacks by crocodiles were all too common.

A baby croc emerges from its mother's jaws, about which an early observer generalized: "a shark's mouth looks innocent by comparison."

A baby croc emerges from its mother's jaws, about which an early observer generalized: "a shark's mouth looks innocent by comparison."