|

|

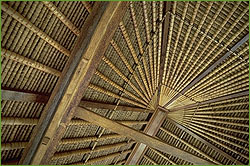

Nature's Miracle Material Part 2 | Back to Part 1 Bamboo can outgrow any other plant in the world. It is as if its entire lifespan is one enormous growth spurt. To see for himself how fast bamboo can grow, Janssen once marked a stalk while visiting a bamboo plantation. He remembers taking a walk around the plantation and returning again to the marked stalk. "In two hours, it had grown above the mark by a few centimeters," he says. A Japanese scientist once measured what is believed to be the fastest growth rate for any bamboo. A culm of ma-dake, Japan's most common bamboo, grew nearly four feet in one 24-hour day. As in so many other cultural and technological developments (see China's Age of Invention), the Chinese have been at the forefront of bamboo technology for a millennium. Their ancient dictionary, the Erh Ya, written 2,000 years ago, includes a reference to bamboo, and the Chinese character chu - which indicates good sense - is depicted as two leafed twigs of bamboo. The character appears in hundreds of other Chinese words and phrases. It is believed the Chinese first split and glued bamboo well over 1,000 years ago. In the last half-century, the nation has become a giant exporter of bamboo and bamboo products. China exports the material in various forms all over the world, with Europe being its leading customer. There, farmers and gardeners utilize the material as support stakes for garden and farm plants such as tomatoes, melons, hops, and fruits. Scandinavians use narrower stalks for ski poles and to mark the edges of roads. The widest stalks from the mao chu variety, sometimes two inches wide, end up in fishing rods and furniture.

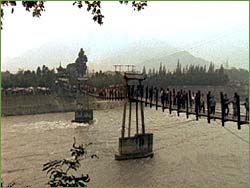

Bamboo Bridges Some of the earliest of all suspension bridges were ones constructed with cables woven from bamboo strips. Throughout their long history, the Chinese have built suspension bridges to span fast-flowing rivers and deep ravines, and the Incas also designed hanging bamboo bridges as marvelous as those of the Chinese, Janssen notes. In "China Bridge," a team of experts brought together by NOVA constructed a suspension bridge using bamboo cables to hang the draping structure. Cabled bamboo strips once held up the great Anlan bridge on the Min River, which historians consider one of the engineering marvels of the ancient world. The bridge hung from bamboo cables from roughly the third century until 1975, when steel cables replaced the bamboo.

The strength of this amazing grass comes from bundles of fibers running the length of the culm and held together by the plant's pith. Rope-makers cut the bamboo into thin strips, weave them together into a rope, and then braid several of these ropes together into a thick and extremely strong cable. Marco Polo, the 13th-century Italian visitor to China, described how fishermen used these extremely tough ropes to tow boats: "The cables. . . are made of. . . the long stout canes of which I have spoken before, fully 15 paces in length. They split them and bind them together into lengths of fully 300 paces, and they are stronger than if they were made of hemp." From Paper to Prescriptions Bamboo has played a less spectacular but perhaps an even more important role in China's development of writing and printing. Long before the Chinese invented paper in the second century B.C., they scratched characters onto slips of green bamboo, and they made books by stringing these slips together with silk strands or sinew. Archeologists recently unearthed one such bundle of bamboo paper, containing over 300 slips, in a 2nd-century B.C. Han Dynasty tomb. Chinese art and literature abounds with images of and references to bamboo. This humble grass often appears as a symbol of resistance to hardship, because one of the features of many bamboo varieties is that they remain green year round.

Like other woods, the material also can be reduced to paper, and in India, it's still one of the most popular woods for paper-making. The amount of paper one can squeeze from an acre of bamboo typically cannot match the wood available from, say, an acre of pine, but bamboo has its own edge. A culm reaches full growth in a few months and can be harvested in a few years. A pine tree may need two decades to mature. The versatile grass also has found its way into China's extensive herbal medicinal chest. Doctors use the rhizome of the black bamboo, mixed with other plants, to treat kidney ailments, and they prescribe the plant's secretion, called tabasheer, for coughs and asthma. Tabasheer also serves as a cooling tonic and even an aphrodisiac in Indian, Chinese, and other Asian cultures. Chinese consider bamboo shoots a delicacy, in part because of the crispness of even the tenderest of shoots. Farmers walk barefoot on the ground to feel for the hard sprouts. To grow softer sprouts, they place a mound of earth on top of the emerging plant so it never encounters light. As desirable as the heart of an artichoke to Westerners, the plant's innermost growing tip is one of the delicacies often reserved for the Chinese market. Photos: (1,2,4) Ed Coll and Carol Bain; (3) The Brett Weston Archive, Corbis; (5,6) NOVA/WGBH; (7) Tony Aruzza, Corbis. NOVA Builds a Rainbow Bridge | Bridge the Gap | Nature's Miracle Material China's Age of Invention | Resources | Transcript Medieval Siege | Pharaoh's Obelisk | Easter Island | Roman Bath | China Bridge | Site Map Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |