Get RealAudio Software 1. Swainson's Thrush RealAudio | AIFF (2.2MB) | WAV (2.2MB) This was recorded in mid-September at about five in the morning. The birds were coming down after a long night of migration, heading southbound out of Canada over central New York. 2. Sora Rail RealAudio | AIFF (218K) | WAV (218K) This was recorded in west central New York in late August. The birds were heading out of the marshes of Canada southbound to areas along the Mid-Atlantic coast. 3. Black-billed Cuckoo RealAudio | AIFF (50K) | WAV (50K) They live in our forests and thickets from southern Canada and eastern North America down to the Ohio Valley. Black-billed Cuckoos winter in South and Central America. 4. American Bittern RealAudio | AIFF (67K) | WAV (67K) American Bitterns nest in southern Canada and the southern U.S. They're secretive during the day but, by monitoring them at night, we realize there are lot more around than we might see during the day. 5. Dickcissel RealAudio | AIFF (410K) | WAV (410K) The Dickcissel nests mainly in central North America. It winters down in South America. 6. Barn Owl RealAudio | AIFF (257K) | WAV (257K) This call can be heard during night migration or when the bird is just out flying during the breading season. The species is common across the central and southern U.S. 7. Upland Sandpiper RealAudio | AIFF (46K) | WAV (46K) Upland Sandpipers live in the prairies and hay fields of central North America. They are a long distance migrant, breeding in the great plains and then migrating to South America. 8. Black and White Warbler RealAudio | AIFF (370K) | WAV (370K) 9. Black and White Warbler (at 1/6th speed) RealAudio | AIFF (176K) | WAV (176K) This call is first played at its normal speed, and then at 1/6th its normal speed. 10. American Redstart RealAudio | AIFF (32K) | WAV (32K) 11. American Redstart (at 1/6th speed) RealAudio | AIFF (76K) | WAV (76K) This note does not have the modulation that the Black and White warbler has. |

Migrating Birds—Bill EvansTo migrate efficiently, birds need to fly high above the topography of the land. But attempting this by day would be suicide for many smaller birds—predators like hawks would surely have them for lunch. The cover of night is more attractive; predators are gone and the atmosphere stabilizes, giving birds a steadier stream of air in which to fly. Night migration also allows for celestial navigation—aiming at a star is much easier than memorizing a complex geographical route. Bill Evans, a researcher at the Laboratory of Ornithology at Cornell University, has been tracking avian migration patterns for more than 10 years.  NOVA: Please describe the subject of your research.

NOVA: Please describe the subject of your research.BE: I study the nocturnal flight calls of migrating birds. Say you're a songbird and you want to go down to Peru for the winter. You'll probably bring a few buddies. The problem is you can't see your buddies when you're flying at night. You might give a little call every once in a while to say,"Here I am, where are you?" and then you'd listen. Then after a few more minutes you might have to call again. After you do this for a while, you'll get some confidence that you're all going in the same direction at the same pace. Another function of the calling may be for air traffic control. Radar show us that there are millions and millions birds migrating across North America on a good night. They're not all going in the same direction or at the same altitude, so there's a lot of traffic up there. By giving these calls, the birds don't crash into each other.

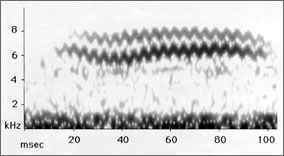

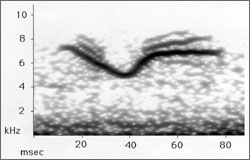

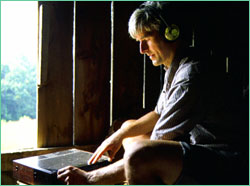

BE: The biggest challenge was figuring out the identities of the different calls. Many of the songbirds give short little call notes called "chips." It's a note, maybe a 10th to a 20th of a second long, that sounds like a single cricket chirp. These calls are high frequency; they're up between five and 10 kilohertz. It's very hard to tell the difference between the chips of the different species. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology has a bio-acoustics research program that developed sound analysis tools. These enable me to run a recording of a bird call into a computer and produce a spectrogram of the sound. I can take these short calls, which my ear can't really discriminate, and make a picture which is like a finger print. I can see the structure on the inside of each call. This has enabled me to make great progress. NOVA: What type of technology did you use in the field?  BE: I learned that the cheapest way to record a long period of time was using

a hi-fi VCR. They're about $200-$300 and have really good sound quality. I

just record the soundtrack, no video. I experimented with a bunch of different

microphone types. What I needed was something inexpensive and water proof that

had good sound quality and I couldn't find anything like that on the market. I

decided to design my own microphone. I built it from a plastic dinner plate

that is about thirteen inches wide. The lips of the plate come up a little

bit and I drill a hole in that and I mount a little hearing aid microphone on

the surface. The plate acts as a reflector. The sound hits the plate and is

picked up by the microphone. I stretched syran wrap over the top of the plate

to make it waterproof. To make the sensitivity pattern of the microphone more

BE: I learned that the cheapest way to record a long period of time was using

a hi-fi VCR. They're about $200-$300 and have really good sound quality. I

just record the soundtrack, no video. I experimented with a bunch of different

microphone types. What I needed was something inexpensive and water proof that

had good sound quality and I couldn't find anything like that on the market. I

decided to design my own microphone. I built it from a plastic dinner plate

that is about thirteen inches wide. The lips of the plate come up a little

bit and I drill a hole in that and I mount a little hearing aid microphone on

the surface. The plate acts as a reflector. The sound hits the plate and is

picked up by the microphone. I stretched syran wrap over the top of the plate

to make it waterproof. To make the sensitivity pattern of the microphone more

NOVA: What did these microphones enable you to learn? BE: Once you know the identity of these bird calls it allows you to take a look at the species that are migrating on a certain night. This has ramifications for population monitoring and also tracking specific migration routes which are important for preserving habitat. It has the potential to be a fantastic way of estimating the numbers of many, many species of birds. Right now that's a very difficult thing cause they're in the woods, they're hard to count, and you can only count a little area at a time. But if we set up microphone stations that are 40 or 50 miles apart across the continent, we can make an acoustic net and monitor the densities of birds crossing it. The exciting possibility that I'm working on with Cornell is to automate this process by using specially designed software to automatically detect and identify these bird calls. Maybe someday we could have something like "migration TV" where you could tune in to the Internet and click on a species that you're interested in and see where they were migrating and in what densities the night before. That's the dream that's pushing this project right now. (back) Photos: (1) Tim W. Gallagher/Cornell Lab of Ornithology; (2) Bill Evans/Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Spectrograms: Bill Evans/Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Night Vision | Zoology After Dark Resources | Guide | Transcript | Night Creatures Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

||||||