|

|

|

|

|

Ground Beetle—Gabor LoveiInsects, due to their vast numbers, are perhaps the most understudied animal group in the world. But Gabor Lovei, a researcher in New Zealand, remains undaunted, having devised a fascinating new way to study beetles at night.  NOVA: Can you describe night-active ground beetles and

explain what makes them interesting?

NOVA: Can you describe night-active ground beetles and

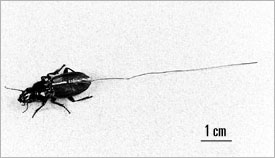

explain what makes them interesting? GL: Ground beetles belong to the beetle family Carabidae. They are widely distributed, and can be found in abundance everywhere, except in deserts. There are about 40,000 known species of ground beetles, and at least as many yet to be described. A typical ground beetle has a proportionate body, long, strong running legs, powerful mandibles and large eyes. Their colors are typically black or brown, often with iridescent colors. NOVA: Describe the greatest challenge studying this insect presented. GL: Most species are night-active. During the day they hide in the ground or in crevices. This, combined with their cryptic coloration makes them very difficult to study.  NOVA: Describe the technology you use in the field.

NOVA: Describe the technology you use in the field.

GL: The equipment I use is called the harmonic radar, which was originally developed to locate avalanche victims. It was first used by two Swedish biologists, Mascanzoni and Wallin, in Uppsala for tracking invertebrate movements around 1985. The equipment consists of a hand-held aerial with a built-in radar wave generator, a battery, a pair of earphones and a passive diode glued to the back of a beetle. The harmonic radar works similarly to metal detectors. The intensity of the reflected signal is related to the distance of the diode from the radar. NOVA: What has this technology has enabled you to learn about night-active ground beetles? GL: By following the beetles during the night, it became possible to find out how far they move, what path they follow, sometimes what they eat or what eats them. We found that their search path is similar to a predator search path—long "walks" (during which the beetles walk almost linearly, sometimes for hundreds of yards) alternate with intensive "searches" of a small area. Well-fed beetles move less than hungry ones. This proves that activity, even during the night, is risky, so beetles that do not have to move (to eat, or to find an individual of the opposite sex to mate), don't. Some species regularly climb trees—it came as a surprise that more species do this than we suspected. NOVA: Describe a typical night in the field. GL: The beetles were collected beforehand and fitted with a transponder. The transponder (made by soldering a diode and a flexible, fine wire coil) was glued on the beetles' backs before taking them out to the study area. We wait until total darkness, and release the beetles, one by one. The release points are marked with a peg. Every 5-15 minutes, we switch on the radar, and start searching for the beetle. We slowly walk in a spiral pattern, starting from the last known point of the beetles' location, and make slow, sweeping motions with the hand-held radar. Guided by the radar, the beetle is relocated, and a new marker peg is placed where it was found. This goes on through the night—or until we fall asleep—or the battery fades. Next day we return and map the walking path of the beetle by measuring the direction and distance of the locations the beetle was found during the night. Then we try to find the beetle. Sometimes the beetle remains in the field for several days, other times it is taken back to the laboratory, and weighed to assess feeding success. This is repeated night after night, until the end of the experiment, or the loss of the beetle. (back) Photos: P. Spring Night Vision | Zoology After Dark Resources | Guide | Transcript | Night Creatures Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |