|

|

|

Going High: The Early Pioneers The earliest written accounts of mountain sickness date back nearly two millenia, but even more ancient evidence of the human urge to venture into thin air exists; the Iceman, for example, was found in the Alps at 10,000 feet on the border of Austria and Italy, and appears to have died in a fierce storm some 5,000 years ago. Scientists are still debating precisely what the Iceman was doing high in the mountains, but written accounts clearly reveal the story of the human quest to go higher, and the gradual discovery of our physiological limitations in extreme altitudes.  Over the centuries, we have learned through trial and error,

and even through the untimely deaths of those who ventured too

high. With the popularity of ballooning in the eighteenth

century and, in the middle of the nineteenth century, alpine

climbing, many theories about the cause of altitude sickness

were advanced. But this century's leap into aviation and space

travel has brought with it a much deeper understanding of the

human ability to function at altitude. The following timeline

relies heavily on research done by Dr. Charles S. Houston,

which resulted in his two valuable books on high altitude,

High Altitude: The History and Prevention of a Killer

and Going Higher: The Story of Man and Altitude.

Over the centuries, we have learned through trial and error,

and even through the untimely deaths of those who ventured too

high. With the popularity of ballooning in the eighteenth

century and, in the middle of the nineteenth century, alpine

climbing, many theories about the cause of altitude sickness

were advanced. But this century's leap into aviation and space

travel has brought with it a much deeper understanding of the

human ability to function at altitude. The following timeline

relies heavily on research done by Dr. Charles S. Houston,

which resulted in his two valuable books on high altitude,

High Altitude: The History and Prevention of a Killer

and Going Higher: The Story of Man and Altitude. c. A.D. 0020

c. A.D. 0020

The earliest known account of mountain sickness can be traced back to the first few decades of the first century A.D.. The account was written by a general to Emperor Wudi of the Han Dynasty: "South of Mount Pishan (in the Karakoram range) the travellers have to climb over Mount Greater Headache, Mount Lesser Headache, and the Fever Hill, where they will develop a fever, turn pallid, feel a headache, and vomit, which also occurs in asses and other animals without exception." In those days, military campaigns, as well as hunting and trading, lured people high into the mountains. Today, scientists are able to attribute such descriptive names of locations to the effects of mountain sickness. A.D. 602-664 In his research, author Dr. Houston uncovered an early account written by perhaps the world's first mountaineer: "An outstanding early mountaineer was Xuan Zang (A.D. 602-664), a Buddhist missionary, whose Travels to the Western Regions describes crossing passes and climbing mountains in the Tien Shan, Kun Lun, and Karakoram ranges. He really loved mountaineering; his highest climb was Lingshan (6,000 meters), making him the first high altitude climber and probably the earliest true mountaineer." Zuan Zang wrote of this high climb: "The journey is arduous and dangerous and the wind dreary and cold. Travellers are often attacked by fierce dragons so that they should neither wear red garments nor carry gourds with them, nor shout loudly. Even the slightest violation of these rules will invite disaster."  1590

1590

In Peru, a Spanish Jesuit priest by the name of Jose de Acosta wrote of the ill effects of altitude that he observed in himself and his companions while crossing a high mountain pass in the Andes: "When I came to mount the degrees, as they call them, which is the top of this mountaine I was suddenly surprised with so mortall and strange a pang, that I was ready to fall from top to the ground....I was surprised with such pangs of straining and casting as I thought to cast up my heart too; for having cast up meate fleugme, and choller, both yellow and greene; in the end I cast up blood with the straining of my stomacke. To conclude, if this had continued, I should undoubtedly have died...I therefore perswade myselfe that the element of the air is there so subtile and delicate, as it is not proportionable with the breathing of man, which requires a more gross and temperate aire, and I beleeve it is the cause that doth so much alter the stomacke, & trouble all the disposition."  October 15, 1783

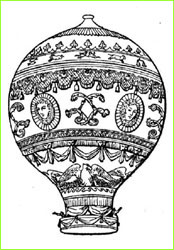

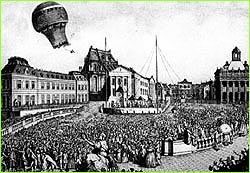

October 15, 1783

The dream of flying was first realized on October 15, 1783 when the balloon "Aerostat Reveillon," carrying Pilatre de Rozier, rose to the end of its 250-foot tether, stayed aloft for 15 minutes, and landed safely. A few weeks later, free flights were made. With the success of lighter-than-air manned ballooning in the years to come (due to the efforts of the French Montgolfier brothers) humans had access to higher elevations than ever before, but no one kenw exactly how high humans could ultimately go.  1850

1850

By the middle of the 19th century, ballooning was in full swing and aeronauts were testing their wings in long distance and high altitude flights to explore the dynamics of lighter-than-air flight. Even by this date, little was known about altitude's effect on human physiology. Nonetheless, one author felt free to expound on the therapeutic effects of high altitude on the body. In his book History and Practice of Aeronautics published in 1850, John Wise suggested, perhaps unwisely, "sending chronically diseased persons through the healthy fields of life-inspiring air above the earth." Wise concluded his book with a chapter subheading that posits "Aerial Voyages are Life Conservative." He wrote: "Now as we rise up in the atmosphere there are two causes acting in beautiful harmony upon the invalid calculated to produce the most happy results. While the most sublime grandeur is gradually opening to the eye and the mind of the invalid—the atmospheric pressure is also gradually diminishing upon the muscular system, allowing it to expand—the lungs becoming more voluminous, taking in larger portions of air at each inhalation, and these portions containing larger quantities of caloric, or electricity, than those taken in on the Earth, and the invalid feels at once the new life pervading his system, physically and mentally. The blood begins to course more freely when up a mile or two with a balloon—the excretory vessels are more freely opened—the gastric juice pours into the stomach more rapidly—the liver, kidneys, and heart, work under expanded action in a highly calorified atmosphere—the brain receives and gives more exalted inspirations—the whole animal and mental system becomes intensely quickened, and more of the chronic morbid matter is exhaled and thrown off in an hour or two while two miles up of a fine summer's day, than the invalid can get rid of in a voyage from New York to Madiera, by sea."  1862

1862

In 1862 a balloon manned by Sir James Glaisher and a companion by the name of Coxwell flew about as high as the summit of Everest. Glacier's written account of that flight describes in detail the rapid deterioration he experienced the higher they ascended, until the point at which he became unconscious. Glaisher lived to recount the experience (as did Coxwell) which appears in the book Ascent from Wolverhampton: "I... looked at the barometer, and found its reading to be 9 3/4 inches, still decreasing fast, implying a height exceeding 29,000 feet. Shortly after I laid my arm upon the table, possessed of its full vigour, but on being desirous of using it I found it powerless—it must have lost its power momentarily; trying to move the other arm, I found it powerless also. Then I tried to shake myself, and succeeded, but I seemed to have no limbs. In looking at the barometer my head fell over my left shoulder; I struggled and shook my body again, but could not move my arms. Getting my head upright for an instant only, it fell on my right shoulder; then I fell backwards, my back resting against the side of the car and my head on its edge. In this position my eyes were directed to Mr. Coxwell in the ring. When I shook my body I seemed to have full power over the muscles of the back, and considerably so over those of the neck, but none over either my arms or my legs. As in the case of the arms, so all muscular power was lost in an instant from my back and neck. I dimly saw Mr. Coxwell, and endeavored to speak, but could not. In an instant intense darkness overcame me, so that the optic nerve lost power suddenly, but I was still conscious, with as active a brain as at the present moment whilst writing this. I thought I had been seized with asphyxia, and believed I should experience nothing more, as death would come unless we speedily descended: other thoughts were entering my mind when I suddenly became unconscious as on going to sleep." 1875 The early pioneers who ventured into thin air flew higher and higher, testing man's adaptability to a rapid ascent to altitude. Unlike mountaineering, where climbers mostly took time to acclimatize, the early balloonists experienced acute exposure to altitude, and some of these attempts proved fatal. The flight of the Zenith from Paris in 1875 resulted in the deaths of two balloonists, Sivel and Croce-Spinelli. Tissandier survived to describe the experience, which appears in Paul Bert's volume, Barometric Pressure.  September 2, 1891

September 2, 1891

About this fateful day, author Dr. Houston wrote: "a young French physician lay desperately ill high on Mont Blanc. He had hurried up from the village of Chamonix to help build a new observatory. The next day he climbed to the summit (4,800 meters; 15,771 feet), and within 24 hours wrote to his brother that, due to mountain sickness, he had never passed so terrible a night. He died three days after arrival, a victim of altitude, and was called 'a martyr to science.' His is the first well-documented case of high altitude pulmonary edema." Lost on Everest | High Exposure | Climb | History & Culture | Earth, Wind, & Ice E-mail | Previous Expeditions | Resources | Site Map | Everest Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |