|

|

|

First to Summit

First to Summitby Audrey Salkeld "We look up. For weeks, for months, that is all we have done. Look up. And there it is—the top of Everest. Only it is different now: so near, so close, only a little more than a thousand feet above us. It is no longer just a dream, a high dream in the sky, but a real and solid thing, a thing of rock and snow, that men can climb. We make ready. We will climb it. This time, with God's help, we will climb on to the end."With their pre-war history of Everest climbing attempts, the British had come to regard the highest mountain in the world with a certain sense of propriety. That Swiss mountaineers had so nearly achieved success in scaling it in 1952 had come as a tremendous shock. The Nepalese government had granted permission for a British assault in 1953, but other nationalities were in line after that and it was by no means certain when a team from Britain might have another opportunity to pit itself against the mountain. If they were to retain their special link with Everest, it was clear in British climbing circles that the mountain had to be climbed in 1953. Moreover, with a new young Queen about to be crowned, it was an auspicious year for demonstrations of British achievement. The pressure to succeed was high, and its first manifestation came in the replacement of Eric Shipton as expedition leader elect by the military mountaineer with a flair for organisation, Colonel John Hunt. To many, this was a shocking, even treacherous move. Eric Shipton was the leading British explorer and a popular and romantic public figure; to oust him now smacked of backdoor diplomacy, and many climbers earmarked for the team wavered over whether to transfer their alliegances to Hunt. For his part, Hunt, the fairest of men, was unhappy with the awkward position he found himself in, and immediately sought to win over the waverers, and indeed Shipton. But Shipton, bitterly disappointed by the turn of events, withdrew from the venture altogether. Apart from the way the matter was handled, the outcome was for the best, for it is doubtful if Shipton could have brought the same utter dedication to the task as did Hunt. Gaining a summit - even the loftiest summit in the world - was never as important to him as seeing what lay around the next corner. He was an explorer, rather than a climber, and wary of over-organization. Hunt put together a very strong team of climbers, picking widely on experience and from keen student mountaineers. No longer was this to be a clique of Alpine Club friends, but the best the country—or rather, the Commonwealth—could offer. New Zealanders Ed Hillary and George Lowe were included in the team, as was Sherpa Tenzing Norgay, who was resident in India, as a full climbing member. Others included: Charles Evans (as Deputy Leader), George Band (at 22, the youngest in the team), Tom Bourdillon, Alf Gregory, Wilfrid Noyce, Dr Mike Ward, Michael Westmacott, and Charles Wylie. Dr Griffith Pugh was the expedition's physiologist, and his preparatory work on Cho Oyu the year before had been instrumental in the planning of all aspects of equipment, clothing, and nutrition, as well as recommended rates and usage of artificial oxygen. His contribution to the team's eventual success should not be under-estimated.  Tom Stobart was the official filmmaker to the enterprise and

James Morris, a correspondent for The Times of London, was

instrumental in sending out the coded message that ensured

news of success broke in England on the Coronation Day of

Queen Elizabeth II. Tom Stobart was the official filmmaker to the enterprise and

James Morris, a correspondent for The Times of London, was

instrumental in sending out the coded message that ensured

news of success broke in England on the Coronation Day of

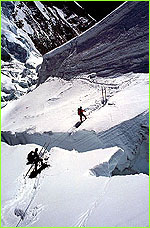

Queen Elizabeth II.With impeccable planning, a series of camps were set up and the expedition route pushed forward up the mountain. A new passage was forged through the awesome and ever-shifting Khumbu Icefall, and the South Face of Lhotse traversed to reach the South Col. On the 26 of May, Charles Evans and Tom Bourdillon, using the closed-circuit oxygen apparatus designed by Bourdillon with his father, launched the first summit attempt. They pushed beyond the Swiss high point of the previous year to surmount the South Summit, at 28,750 feet, less than 300 ft from the summit proper. Unfortunately, one of their oxygen sets was not functioning properly and, bitterly disappointed, they were forced to abort their attempt. Next, it was the turn of Ed Hillary and Tenzing Norgay, generally regarded as the strongest and fittest members of the expedition at that time. An additional high camp was set up above the South Col at 27,900 ft, where the pair spent a fitful night, waiting for dawn. Before first light on the 28th of May the long process of getting warmed up and ready began. It was important to drink what they could to prevent dehydration and their little cooker was started up to melt ice for water. Hillary's boots were frozen and he sought to thaw them out over the little flame. Way down in the darkness the lights of Tengboche Monastery could be seen, where they knew the monks would already be making offererings for their safety. By 6:30 a.m. they were dressed warmly in their down suits and crawled out into the new day, hoisted their oxygen sets onto their shoulders and started kicking steps towards the main ridge and the wash of sunlight. Continue Lost on Everest | High Exposure | Climb | History & Culture | Earth, Wind, & Ice E-mail | Previous Expeditions | Resources | Site Map | Everest Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |