|

|

|

by Gail Rosenbaum  Ever since people began trying to summit Mount Everest,

climbers have become aware of subtle changes in their mental

state as they ascend the mountain—and their brains

gradually receive less oxygen. This year, we have set about

trying to measure changes in the mental abilities of four

people as they climb to ever higher altitudes.

Ever since people began trying to summit Mount Everest,

climbers have become aware of subtle changes in their mental

state as they ascend the mountain—and their brains

gradually receive less oxygen. This year, we have set about

trying to measure changes in the mental abilities of four

people as they climb to ever higher altitudes. Our premise is that the higher you go, the slower you think, and the more difficult it is to think a problem through. To quantify this, we have put together a small battery of tests that the climbers will take at predetermined stops along the route to the summit. In March, we tested the climbers at sea level to establish their "baseline"—or how they function  under normal conditions. Different versions of the same tests

will be given to the climbers as they ascend. To prevent the

climbers from relying on the effect of practice or memory to

help them respond, they do not know in advance what specific

questions will be asked.

under normal conditions. Different versions of the same tests

will be given to the climbers as they ascend. To prevent the

climbers from relying on the effect of practice or memory to

help them respond, they do not know in advance what specific

questions will be asked. One change we expect to see in the climbers as they ascend is that they will not be able to remember things easily, and that it will be more difficult for them to get the words out of their mouths. In order to see if this is true, they will be asked to listen to sentences, which will be read to them via radio from Base Camp, and then try to repeat them word for word. We will be timing how long they take to repeat the sentences, and counting the number of errors.  Another test will look at the ability to solve simple

verbal puzzles. A

typical question will be, "If John is taller than Tom, who is

shorter?" This puzzle is fairly simple to analyze at sea

level, but as the climbers reach higher altitudes, we expect

to see them struggling to come up with the correct answer, or

perhaps even answering incorrectly. Again, this will be

measured by how long it takes them to respond, and by whether

or not they respond correctly.

Another test will look at the ability to solve simple

verbal puzzles. A

typical question will be, "If John is taller than Tom, who is

shorter?" This puzzle is fairly simple to analyze at sea

level, but as the climbers reach higher altitudes, we expect

to see them struggling to come up with the correct answer, or

perhaps even answering incorrectly. Again, this will be

measured by how long it takes them to respond, and by whether

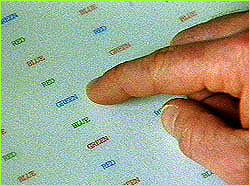

or not they respond correctly.Another area we will look at is the speed with which they process information. To examine this cognitive ability, the climbers will read simple statements to which they will have to answer 'true' or 'false' via radio. Typical statements are "Rats are built in factories," or "Desks wear clothes," or "Ants are insects." Some of these statements are patently absurd when you think about them at sea level, but at altitude we may find that the climbers have to think twice before they can respond, or again, that they may respond incorrectly. We will also be looking at how well the climbers can pay attention, through a special sound test. The climbers will be asked to listen to a tape which plays a series of sounds, some of which are high, and some of which are low. The climbers must count the number of low tones, while ignoring the high ones. One test which the climbers and others find very difficult is the Stroop test. It is a test of one's mental flexibility. In this test, you have to make yourself inhibit, or stop one response, and say something else. In one such test, the climbers will see  words with the names of colors, but the actual words will be

different from the color in which they are written. For

example, the word 'blue' will be written in green ink. The

climbers will have to say the color they see, and disregard

the word they read. This is much harder than it sounds, and we

expect to see the climbers' mental flexibility decrease with

altitude.

words with the names of colors, but the actual words will be

different from the color in which they are written. For

example, the word 'blue' will be written in green ink. The

climbers will have to say the color they see, and disregard

the word they read. This is much harder than it sounds, and we

expect to see the climbers' mental flexibility decrease with

altitude. Although we hope to obtain some very interesting data from these tests, four climbers is not a large enough sample to answer the question of whether judgment is compromised at very high altitude. However, we will begin to gain new insight from these neuro-behavioral tests as to whether it takes longer to think and evaluate information, how that changes with increasing altitude, and how it can vary from one person to another. We also have to keep in mind, however, that some of the changes we will see in the ability to process information might be due to effects other than lack of oxygen. The climbers may also be affected by lack of sleep, general physical fatigue, diet, climate, or any number of other variables. We are all waiting eagerly to see what our data will look like. Will we see the changes we expect from sea level to the top of the mountain? Will there be a measurable difference between the climbers' ability with and without oxygen at the summit? Will we get some surprises? Will we see some results we don't expect, such as improvements in some cognitive abilities, and deterioration in others? All of these questions reveal that very little is known about altitude's effect on the brain and one's ability to problem-solve in mentally taxing situations. Gail Rosenbaum is the Associate Director and Supervising Psychometrist at the Neuropsychology Laboratory at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle. She has worked in a clinical setting for many years doing psychometric testing to evaluate brain function. Besides being involved in a previous high altitude study, she has been involved in AIDS research and is currently working on a study looking at the neuropsychological effects of dental amalgam in children in Portugal. Photos: (1) MRI of Ed Viestur's brain; (2) Howard Donner and Gail Rosenbaum test David Carter (center) at sea level; (3) Howard Carter uses stopwatch to time David Carter; (4) David Carter reads the Stroop Test. Lost on Everest | High Exposure | Climb | History & Culture | Earth, Wind, & Ice E-mail | Previous Expeditions | Resources | Site Map | Everest Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |