Pandemic Flu

- Posted 01.10.06

- NOVA scienceNOW

(This video is no longer available for streaming.) In 1918, bird flu randomly acquired the gene for coughing and sneezing. This version of the bird flu didn't do much to birds, but when it somehow made the jump into people, it killed up 50 million people worldwide. Could this happen again, with the H5N1 avian flu? In this video, NOVA scienceNOW host Robert Krulwich talks to Kanta Subbarao of the National Institutes of Health about the threat.

Transcript

PANDEMIC FLU

PBS Airdate: January 10, 2006

ROBERT KRULWICH: So not only did a woodpecker make news last year, birds themselves were a big item, very big: the subject of international summits, White House conferences. I'm talking, of course, about bird flu. And very particularly, I'm talking about something that probably hasn't happened yet, but could. And that raises a question.

So far, this new bird flu has not acquired the ability to travel on a cough or a sneeze, through the air, from one infected person to another. But what everybody wants to know is, could it learn how? And what are the odds?

Well, if you look at a virus, any virus, you'll find a recipe, a genetic recipe, a lot of instructions spelled out in chemicals, abbreviated A, C, G and U. Everything a virus knows comes from these instructions. So somewhere in the human virus there's an instruction that says, "When you infect a person, infect him here in the upper respiratory tract—not in the lungs, not in the tummy—just up here, and make the person, the host cough." 'Cause what gets the virus out, it's the way the virus transmits.

It's different in a bird. In a bird flu, the bird virus has an instruction that says "Infect the gut, and give the bird diarrhea, so it leaves droppings." And mostly it's the droppings that transmit the virus for birds.

So we do it here, they do it there. The bird virus, therefore does not need an instruction for coughing and sneezing.

But here's the bad news: back in 1918 or so, bird flu somehow acquired the gene for coughing and sneezing. It wasn't much use, it just sat there in birds. But when that virus got into people, that bird flu—because it could pass through the air—that flu killed 50 million people. So you may ask, "Well, in 1918, how did that happen?"

KANTA SUBBARAO: The 1918 viruses have acquired the necessary characteristics to infect people and transmit efficiently.

ROBERT KRULWICH: By accident?

KANTA SUBBARAO: Un-huh.

ROBERT KRULWICH: According to Kanta Subbarao, one of the nation's leading flu investigators, the 1918 bird flu got its cough and sneeze transmissibility by mistake. It was a random event that happened kind of like this: are you familiar with the old saw that if you put an infinite number of monkeys in front of an infinite number of typewriters, you would eventually get Hamlet?

KANTA SUBBARAO: I haven't heard that.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Okay, well let me explain it a bit. Imagine one monkey hitting a typewriter at random; he doesn't know what he's typing. But now, let's make it an infinite number of monkeys. And infinite is a whole lot of monkeys, so many that, eventually, some monkey somewhere is going to, completely at random, produce a perfect copy of Hamlet.

Well, in a similar manner, when one bird gets sick with bird flu, as it gets sick, inside the bird the virus is spreading, copying itself over and over and over, maybe a hundred million times. And if you've got a lot of birds, like this crowd here, that means in all these animals, altogether there could be 10 trillion viruses. So if you're asking, "What are the chances of a bird flu accidentally creating the ability to travel on a cough or a sneeze?" Well, it's kind of like the monkeys and the typewriters.

If you're looking at 10 trillion viruses and all you need is one mistake, just one, that spells out the right recipe, that could happen. I mean, you've got 10 trillion chances.

But here's the big surprise. When I said to Dr. Subbarao, "When we look at a human virus, do we know where in this sea of letters...would you know where this cough and sneeze ability is?"

KANTA SUBBARAO: Unfortunately not.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Hasn't it occurred to people to try and figure it out?

KANTA SUBBARAO: But it's a difficult thing to do.

ROBERT KRULWICH: So scientists don't know if the recipe is a few letters long— very simple—or if it's thousands of letters long and very complicated.

KANTA SUBBARAO: Nobody's sure yet.

ROBERT KRULWICH: What you don't know is a lot.

KANTA SUBBARAO: That's true.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Since we don't know the recipe, the genetic recipe, for coughing and sneezing, we can't figure the odds. Try it yourself.

Let's say this guy's chickens are all sick with bird flu, and he's got, let's see, one, two, three, four, five chickens, which means...so he's sitting next to 500 million bird flu viruses. And I ask you, "What are the chances there's a cough and sneeze virus right here ready to infect him?"

Well, if the recipe for coughing and sneezing is 13 letters long, if it's very simple, and there are 500 million viruses in his chickens? Seems likely, kind of like just one of these monkeys accidentally typing a little bit of Shakespeare, sure. But if the recipe for coughing and sneezing is 13,000 letters long, in a very precise order, that's like one monkey accidentally typing the first two acts of Hamlet perfectly. Those are very different odds.

So if we don't know the recipe, we really can't know the odds. And remember, even if this chicken, or it could be a duck or a goose, has randomly created the cough and sneeze virus, that virus still somehow has to get from this bird to this man.

KANTA SUBBARAO: That's right. That's right. So there is, there are all these events that probability...has to sort of all come together: the, the, the chance of the mutations and exposure to a susceptible host.

ROBERT KRULWICH: This seems like such long odds to me: got to have the sick duck, the sick duck has to be near a person who's vulnerable, the person has to suck in the virus, the virus has to attach. And yet it happened. It may sound wildly improbable, but in 1918, it did happen, so there is a danger.

But since we don't know the recipe for coughing and sneezing, when you read stories that seem to know the odds, that say the bird flu "is coming," or the worldwide pandemic is "inevitable," or it's "overdue," or "around the corner," be skeptical. We know this flu is dangerous to birds. We don't know if it'll be dangerous to humans tomorrow, or next year, or decades from now. We just don't know.

Credits

Pandemic Flu

- Executive Producer

- Samuel Fine

- Executive Editor

- Robert Krulwich

- Senior Series Producer

- Vincent Liota

- Senior Producer

- Robe Imbriano

- Producers

- Julia Cort

Carla Denly

Robe Imbriano

Dean Irwin

Vincent Liota

Mary Robertson

Win Rosenfeld - Editors

- Ben Ehrlich

Nathan Hendrie

Robe Imbriano

Vincent Liota

Win Rosenfeld - Supervising Producer

- Andrea Cross

- Development Producer

- Kyla Dunn

- Program Editor

- Steve Trevisan

- Associate Producers

-

Anthony Manupelli

Mary Robertson

Win Rosenfeld

Ayo Babatunde

Shimona Shahi - Unit Manager

- Candace White

- Production Secretary

- Ayo Babatunde

- Compositing

- Yunsik Noh

- Production Assistant

- Robbie Gemmel

- Music

- Rob Morsberger

- NOVA scienceNOW Series Animation

- Edgeworx

- Camera

- Chris Borghesani

George Delgado

Brian Dowley

Tom Fahey

Vikram Gandhi

Robert Hanna

Michael Hunkley - Sound Recordists

- Paul Austin

Vikram Gandhi

Mike Karas

Dennis McCarthy

Gilles Morin

Alex Sullivan - Audio Mix

- John Jenkins

- Animation

- Mitch Butler

Edgeworx

Picket Design

Pie Design - Special Thanks

- Clifford Cunningham

Foxwoods Resort Casino

The Graduate Center at CUNY

Alex Meissner

Naturally Tasty Health Food

The New York Number Theory Seminar

The officers and crew of the NOAA ships Delaware II and Albatross IV

Jí¡nos Pintz

Salon Mario Russo

Cem Yildirim

Adam Zoghlin - Archival Material

- ABC News Video Source

Art. Lebedev Studio

Mike Brown, Caltech

Michael Brumlik

Jewel Webb Chambers

CNN

CORBIS Motion

Michael DiGiorgio, Worldwide Nature Artists Group

Denis Finnin, American Museum of Natural History

Richard Gibbe

Dennis Kunkel Microscopy, Inc.

Robert Hurt (IPAC)

Jupiterimages Corporation

The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology

MODIS Rapid Response Project at NASA/GSF

Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University

NASA/JPL

NASA/JPL-Caltech

Jay Pitocchelli

Prairie Pictures / StormStock, Martin Lisius

24 Images

N. John Schmitt

Ultimate Chase Stock Video

Mitch Waite

WWL-TV - NOVA Series Graphics

- yU + co.

- NOVA Theme Music

- Walter

Werzowa

John Luker

Musikvergnuegen, Inc. - Additional NOVA Theme Music

- Ray Loring

- Post Production Online Editor

- Spencer Gentry

- Closed Captioning

- The Caption Center

- NOVA Administrator

- Dara Bourne

- Publicity

- Eileen Campion

Olivia Wong - Senior Researcher

- Barbara Moran

- Production Coordinator

- Linda Callahan

- Unit Managers

- Lola

Norman-Salako

Carla Raimer - Paralegal

- Richard Parr

- Legal Counsel

- Susan Rosen Shishko

- Post Production Assistant

- Alex Kreuter

- Associate Producer, Post Production

- Patrick Carey

- Post Production Supervisor

- Regina O'Toole

- Post Production Editor

- Rebecca Nieto

- Post Production Manager

- Nathan Gunner

- Supervising Producer

- Stephen Sweigart

- Producer, Special Projects

- Susanne Simpson

- Coordinating Producer

- Laurie Cahalane

- Senior Science Editor

- Evan Hadingham

- Senior Series Producer

- Melanie Wallace

- Managing Director

- Alan Ritsko

- Senior Executive Producer

- Paula S. Apsell

NOVA scienceNOW is a trademark of the WGBH Educational Foundation

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0229297. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

© 2006 WGBH Educational Foundation

All rights reserved

- Image credit: (chickens) © CORBIS

Participants

- Kanta Subbarao

- National Institute of Health

Related Links

-

Pandemic Flu: Expert Q&A

Dr. Kanta Subbarao of the National Institutes of Health answers questions about pandemic flu, avian and otherwise.

-

1918 Flu

A virus that killed up to 50 million people is brought back to life to decipher its deadliness.

-

Reviving the 1918 Virus

Why recreate the deadly 1918 flu virus? In this interactive poll, explore arguments for and against then vote online.

-

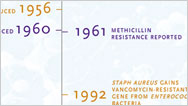

Arms Race With a Superbug

Certain microbes evolve defenses against every antibiotic we throw at them. Staph aureus is a sobering case in point.

-

Killer Microbe

A relatively benign bug becomes a highly lethal pathogen, known to U.S. soldiers as Iraqibacter.