Discovering Exercise in a Pill

- By Bang Wong & Susan K. Lewis

- Posted 05.01.09

- NOVA scienceNOW

Scientists at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California have found two different drugs that can mimic the effects of exercise in remarkable ways. In this interactive, one of the lead researchers, Vihang Narkar, guides you through a simplified, cartoon version of the experiments behind the discovery.

Launch Interactive

Launch Interactive

Try our mouse-racing experiments to learn how drugs that mimic exercise were discovered and how they work.

Transcript

Discovering Exercise in a Pill

NARRATOR: Okay, so first of all, this is not an actual lab notebook. But open it up, and we'll show you how scientists have discovered not just one, but two different drugs that seem to have the benefits of exercise. And you'll get to try some experiments of your own.

NARRATOR: We've asked Vihang Narkar, who did much of the research, to be our guide. Vihang works in Ron Evans lab at the Salk Institute.

VIHANG NARKAR: When I came to the lab in 2004, Ron and other scientists here were investigating a gene that they knew played a big role in metabolism, which is really how the body processes sugars and fat and actually turns them into energy.

VIHANG NARKAR: This gene also seemed to play a role in endurance—or how long muscles can keep going without tiring. So we wanted to see whether it might be possible to "turn on" this endurance gene or the receptor, which is called PPAR delta, using a drug.

NARRATOR: They found a drug called GW1516 that they thought could possibly turn a couch potato mouse into an athlete – the rodent equivalent of a Lance Armstrong. But would it work?

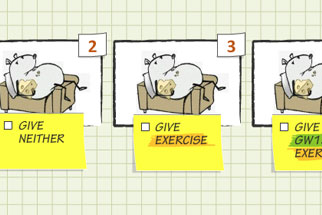

NARRATOR: Try it yourself. Here are four mice that are a lot easier to work with than the real thing.

Check off the to-do items on the post-its.

NARRATOR: Alright. It's time to race some mice.

Click and drag your mice and move them to the start of the track.

VIHANG: So what happened was not what I expected.

The mice who got the drug but hadn't gotten exercise showed absolutely zero improvement in their performance. They ran no better than the couch potatoes.

NARRATOR: Yet this drug, when combined with exercise, the drug was working really well.

VIHANG: We realized that the gene PPAR Delta is sort of like a master switch that turns on lots of other endurance genes. And that on it's own, the drug GW1516 wasn't that effective in turning on all these endurance genes.

NARRATOR: Yet somehow, when combined with exercise, the drug was working really well.

VIHANG: So we thought, let's take a look at how exercise builds endurance.

NARRATOR: It's common knowledge that the more you run, the better you get at running long distances. Why is this?

VIHANG: As you run, inside your muscle cells, chemical energy—called ATP—is consumed. This leaves a waste product called AMP. The build up of this waste product then triggers another protein called AMP kinase.

NARRATOR: And it's this AMP kinase, working together with PPAR delta, that turns on the various endurance genes that help us run long distances.

In a similar way, the drug GW1516 works together with AMP kinase, this byproduct of exercise, with great results.

So the next question was: Could they find another drug that would trick the body into making AMP kinase?

VIHANG: We found a drug called AICAR, which is chemically similar to AMP, and we designed a new set of experiments to find out if we could trick the body into activating AMP kinase, revving up the same endurance genes that are activated by exercise.

NARRATOR: Could AICAR have the same impact as exercise? Try out some more experiments yourself. Check off the to-do items on the post-it notes.

It's race time again. Click and drag your mice to the start of the racetrack.

VIHANG: Experimenting with this new drug, AICAR, we got more surprising results. We had suspected that AICAR, given together with GW1516, might improve endurance. But it turned out that AICAR, all by itself, also worked.

NARRATOR: After just four weeks on AICAR, the couch potato mice could run about 45 percent longer than the mice that didn't get the drug. They looked leaner and healthier, too.

VIHANG: So after all our experiments (which were a bit more complicated than the ones with our cartoon mice) what lessons did we learn?

First, we learned that the drug AICAR seems to be a pretty good substitute for exercise.

NARRATOR: But AICAR, though, is still no substitute for intense exercise. It can't replicate the training of a marathon runner, and it won't turn a couch potato into a Lance Armstrong.

But because it works all by itself, AICAR could be a critical drug for people who can't exercise at all. And for people who can exercise GW1516 could act as a boost, helping them build endurance faster.

VIHANG: In the end, we identified two different biological pathways for turning on endurance genes, and two different drugs that can act as "exercise pills."

NARRATOR: You might wonder, can these drugs really have all the amazing benefits of exercise?

VIHANG: Well, we know that at least in our lab mice, the drugs helped activate various genes that transformed the muscle in their bodies, helping them to burn more fat and run longer without tiring.

They were also leaner, and they showed improvements in their cholesterol and insulin levels.

But exercise has so many fantastic benefits—mood enhancement, possibly protection against Alzheimer's—many other benefits that we were not testing for with these drugs.

NARRATOR: And all of this research, of course, took place in laboratory mice. We're far from having "an exercise pill" you can buy at a pharmacy. And even if you could, there are still many reasons to keep exercising the old-fashioned way.

Credits

Related Links

-

Marathon Mouse

With an "exercise pill," researchers turn couch-potato rodents into champion runners.

-

Aiding Aging Muscles

See how "exercise in a pill" could one day help the elderly and the bedridden.

-

Marathon Mouse: Expert Q&A

Ron Evans and Vihang Narkar of the Salk Institute answer questions about "exercise in a pill," burning fat, and more.

-

Our Improbable Ability to Walk

How do we two-legged, top-heavy pillars of flesh and bone possibly stay upright while in motion?

You need the Flash Player plug-in to view this content.