|

|

|

|

History of Biowarfare

Medieval Siege |

American Revolution |

WW I | WW II |

Cold War |

Soviet "Superbugs" |

Iraq's Secret Weapons |

The Cults |

Anthrax Attacks

|

When loaded with diseased bodies, wood-frame

catapults were biological weapons.

When loaded with diseased bodies, wood-frame

catapults were biological weapons.

|

Medieval Siege

In the 14th and 15th centuries, little

was known about how germs cause disease. But according to

medieval medical lore, the stench of rotting bodies was

known to transmit infections. So when corpses were used as

ammunition, they were no doubt intended as biological

weapons.

Three cases are well-documented:

1340

Attackers hurled dead horses and other animals by catapult

at the castle of Thun L'Eveque in Hainault, in what is now

northern France. The defenders reported that "the stink and

the air were so abominable...they could not long endure" and

negotiated a truce.

1346

As Tartars launched a siege of Caffa, a port on the Crimean

peninsula in the Black Sea, they suffered an outbreak of

plague. Before abandoning their attack, they sent the

infected bodies of their comrades over the walls of the

city. Fleeing residents carried the disease to Italy,

furthering the second major epidemic of "Black Death" in

Europe.

1422

At Karlstein in Bohemia, attacking forces launched the

decaying cadavers of men killed in battle over the castle

walls. They also stockpiled animal manure in the hope of

spreading illness. Yet the defense held fast, and the siege

was abandoned after five months.

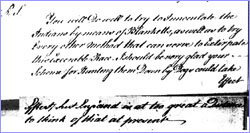

Gen. Jeffrey Amherst, in a letter dated 16 July

1763, approved the plan to spread smallpox to

Delaware Indians.

Gen. Jeffrey Amherst, in a letter dated 16 July

1763, approved the plan to spread smallpox to

Delaware Indians.

|

|

American Revolution

While the first true vaccine for smallpox was not invented

until 1796, the practice of deliberately inoculating people

with a mild form of the disease was established decades

earlier. The British military likely employed such

deliberate infection to spread smallpox among forces of the

Continental Army.

The British routinely inoculated their own troops, exposing

soldiers to the material from smallpox pustules to induce a

mild case of disease and, once they recovered, life-long

immunity. But in Boston, and perhaps also Quebec, the

British may have forced smallpox on civilians. As they fled

the besieged cities these civilians, the British hoped,

would carry smallpox to rebel troops.

In Boston the mission seems to have failed; the infected

civilians were quarantined and thus kept from Continental

soldiers. But in Quebec, smallpox swept through the

Continental Army, helping to prompt a retreat.

Using smallpox as a weapon was not unprecedented for the

British military; Native Americans were the targets of

attack earlier in the century. One infamous and

well-documented case occurred in 1763 at Fort Pitt on the

Pennsylvania frontier. British Gen. Jeffery Amherst ordered

that blankets and handkerchiefs be taken from smallpox

patients in the fort's infirmary and given to Delaware

Indians at a peace-making parley.

|

After the war, cavalries were trained to expect

attacks with chemical and biological weapons.

After the war, cavalries were trained to expect

attacks with chemical and biological weapons.

|

World War I

By the time of The Great War, the germ theory of disease was

well established; scientists grasped how microbes such as

bacteria and viruses transmit illness. During the war,

German scientists and military officials applied this

knowledge in a widespread campaign of biological

sabotage.

Their target was livestock—the horses, mules, sheep,

and cattle being shipped from neutral countries to the

Allies. The diseases they cultivated as weapons were

glanders and anthrax, both known to ravage populations of

grazing animals in natural epidemics. By infecting just a

few animals, through needle injection and pouring bacteria

cultures on animal feed, German operatives hoped to spark

devastating epidemics.

Secret agents waged this campaign in Romania and the U.S.

from 1915-1916, in Argentina from roughly 1916-1918, and in

Spain and Norway (dates and details are obscure). Despite

the claims of some agents, their overall impact on the war

was negligible.

The much more apparent horrors of chemical warfare led, in

1925, to the Geneva Protocol. It prohibits the use of

chemical and biological agents, but not research and

development of these agents.

The United States signed the Protocol, yet 50 years passed

before the U.S. Senate voted to ratify it. Japan also

refused to ratify the agreement in 1925.

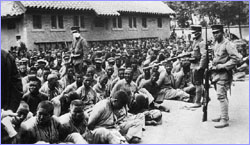

The Japanese army used Chinese prisoners to test

bioweapons. (These particular men may not have been

subjects.)

The Japanese army used Chinese prisoners to test

bioweapons. (These particular men may not have been

subjects.)

|

|

World War II

While Germany dabbled with biological weapons in World War

I, the Japanese military practiced biowarfare on a mass

scale in the years leading up to and throughout World War

II. Directed against China, the onslaught was spearheaded by

a notorious division of the Imperial Army called Unit

731.

In occupied Manchuria, starting around 1936, Japanese

scientists used scores of human subjects to test the

lethality of various disease agents, including anthrax,

cholera, typhoid, and plague. As many as 10,000 people were

killed.

In active military campaigns, several hundred thousand

people—mostly Chinese civilians—fell victim. In

October 1940, the Japanese dropped paper bags filled with

plague-infested fleas over the cities of Ningbo and Quzhou

in Zhejiang province. Other attacks involved contaminating

wells and distributing poisoned foods. The Japanese army

never succeeded, though, in producing advanced biological

munitions, such as pathogen-laced bombs.

As the leaders of Unit 731 saw Japan's defeat on the

horizon, they burned their records, destroyed their

facilities, and fled to Tokyo. Later, in the hands of U.S.

forces, they brokered a deal, offering details of their work

in exchange for immunity to war crimes prosecution.

By the end of WWII, the Americans and Soviets were far along

on their own paths in developing biological weapons.

|

Weapons production at Fort Detrick, Maryland, the

U.S. Army's base for biowarfare research.

Weapons production at Fort Detrick, Maryland, the

U.S. Army's base for biowarfare research.

|

Cold War

While ignited by World War II, bioweapons programs in the

Soviet Union and the U.S. reached new heights in the anxious

climate of the Cold War. Both nations explored the use of

hundreds of different bacteria, viruses, and biological

toxins. And each program devised sophisticated ways to

disperse these agents in fine-mist aerosols, to package them

in bombs, and to launch them on missiles.

In 1969, the U.S. military celebrated the success of a

massive field test in the Pacific. The

wargame—involving a fleet of ships, caged animals, and

the release of lethal agents—provided proof of the

impact of bioweapons. Little did the U.S. team know,

however, that Soviet spies were in nearby waters, collecting

samples of the agents tested.

At the end of 1969, likely prompted by Vietnam War protests,

President Richard Nixon terminated the offensive biological

warfare program and ordered all stockpiled weapons

destroyed. From this point on, U.S. researchers switched

their focus to defensive measures such as developing

"air-sniffing" detectors.

In 1972, the U.S. and more than 100 nations sign the

Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention, the world's first

treaty banning an entire class of weapons. The treaty bars

possession of deadly biological agents except for defensive

research. Yet no clear mechanisms to enforce the treaty

existed. And just as it signed the treaty, the Soviet Union

fired up its offensive program.

Soviet "Superbugs"

In 1979, a rare outbreak of anthrax disease in the city of

Sverdlovsk killed nearly 70 people. The Soviet government

publicly blamed contaminated meat, but U.S. intelligence

sources suspected the outbreak was linked to secret weapons

work at a nearby army lab.

In 1992, Russia allowed a U.S. team to visit Sverdlovsk. The

team's investigation turned up telltale evidence in the

lungs of victims that many died from inhalation anthrax,

likely caused by the accidental release of aerosolized

anthrax spores from the military base. Given the hundreds of

tons of anthrax the Sverdlovsk facility could produce, the

release of just a small amount of spores was fortunate.

News of the immensity of the Soviets' biological weapons

program began to reach the West in 1989, when biologist

Vladimir Pasechnik defected to Britain. The stories he

told—of genetically altered "superplague,"

antibiotic-resistant anthrax, and long-range missiles

designed to spread disease—were confirmed by later

defectors like Ken Alibek and Sergei Popov.

The Soviet program was spread over dozens of facilities and

involved tens of thousands of specialists. In the late 1980s

and 1990s, many of these scientists became free

agents—with dangerous knowledge for sale.

|

During Operation Desert Storm, the U.S. military

feared that Scud missiles might contain biological

agents.

During Operation Desert Storm, the U.S. military

feared that Scud missiles might contain biological

agents.

|

Iraq's Secret Weapons

As the Soviet Union's program began to crumble in the 1990s,

and scientists' salaries dwindled, some bioweapons experts

may have been lured to Iraq. Iraq launched its own

bioweapons program around 1985 but initially lacked the

expertise to develop sophisticated arms.

By the time of the Gulf War cease-fire in 1991, however,

Iraq had weaponized anthrax, botulinum toxin, and aflatoxin

and had several other lethal agents in development.

Inspectors from the U.N. Special Commission (UNSCOM) spent

frustrating years chasing down evidence of the program,

which Iraq repeatedly denied existed. The UNSCOM team found

that Iraq's stockpile included Scud missiles loaded to

deliver disease.

Iraq is known to have unleashed chemical weapons in the

1980s, both during the Iran-Iraq war and against rebellious

Kurds in northern Iraq. But there is no evidence that the

Iraqi state has ever used its biological arsenal.

What is almost certain, though, is that this arsenal still

exists in 2001. In fact, with the aid of former Soviet

experts and UNSCOM inspectors kept at bay, the Iraqi arsenal

is likely growing in power.

The Aum Shinrikyo cult claimed tens of thousands of

members.

The Aum Shinrikyo cult claimed tens of thousands of

members.

|

|

The Cults

In 1984, followers of the Indian guru Bagwan Shree Rajneesh,

living on a compound in rural Oregon, sprinkled

Salmonella on salad bars throughout their county. It

was a trial run for a proposed later attack. The

Rajneeshees' scheme was to sicken local citizens and thus

prevent them from voting in an upcoming election.

The trial attack was successful; it triggered more than 750

cases of food poisoning, 45 of which required

hospitalization. The Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention launched an investigation but concluded that the

outbreak was natural. It took a year, and an independent

police investigation, to discover the true source of the

attack.

While this first bioterrorist act on American soil went

almost unnoticed, a decade later the work of another cult

sparked a flurry of media coverage and government

response.

In 1995, the apocalyptic religious sect Aum Shinrikyo

released sarin gas in a Tokyo subway, killing 12 commuters

and injuring thousands. The cult also had enlisted Ph.D.

scientists to launch biological attacks. Between 1993 and

1995, Aum Shinrikyo tried as many as 10 times to spray

botulinum toxin and anthrax in downtown Tokyo.

Just why the attacks failed is not known, but some experts

suspect the cult did not sufficiently refine the particle

size of its agents and that it was working with an avirulent

strain of anthrax.

|

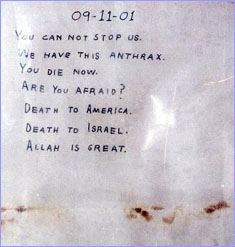

When these letters were opened, the fine-grained

anthrax within them misted into the air.

When these letters were opened, the fine-grained

anthrax within them misted into the air.

|

Anthrax Attacks

For more than two decades, bioterrorism experts warned that

America may be vulnerable to attack with biological weapons.

In the fall of 2001, these warnings took on a new urgency.

A week after the terrorist attacks of September

11th, a letter containing anthrax spores was

mailed to Tom Brokaw at NBC News in New York. Two other

letters with nearly identical handwriting, venomous

messages, and lethal spores arrived at the offices of the

New York Post and Senator Tom Daschle in Washington,

D.C.

By the end of the year, 18 people had been infected with

anthrax, five people had died of the inhaled form of the

disease, and hundreds of millions more were struck by

anxiety of the unknown.

As New York Times reporter Judith Miller notes in

NOVA's "Bioterror," the anthrax-laced letters sparked "mass

disruption" rather than "mass destruction."

But the story is continuing to unfold.

Photos: (1) WGBH/NOVA; (2,5) National Archives and Records

Administration; (3) Native Web, www.nativeweb.org; (4,

6-10) Corbis Images.

History of Biowarfare

|

Future Germ Defenses

Interviews with Biowarriors

|

Global Guide to Bioweapons

|

Making Vaccines

Resources

|

Teacher's Guide

|

Transcript

|

Site Map

|

Bioterror Home

Search |

Site Map

|

Previously Featured

|

Schedule

|

Feedback |

Teachers |

Shop

Join Us/E-Mail

| About NOVA |

Editor's Picks

|

Watch NOVAs Online

|

To Print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

©

| Updated February 2002

|

|

|

|