Parents Might Pass the Effects of Prozac on to Future Generations

Treating zebrafish embryos with the active ingredient in Prozac can compromise the stress responses of generations to come.

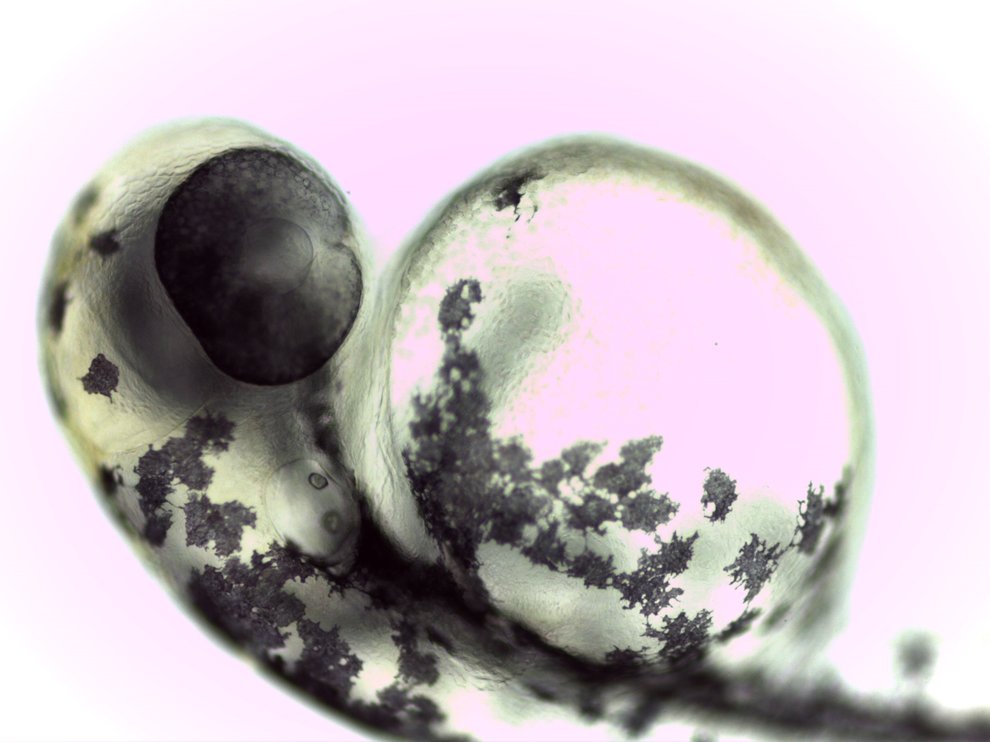

Exposing a developing embryo to Prozac could affects its hormones and behavior later in life—and these effects may even pass on to future generations. Photo Credit: Vasyl Dolmatov, iStock

There are few relationships more biologically intimate than the one between a mammalian mother-to-be and her growing fetus. But the dialogue of pregnancy can be a double-edged sword.

All sorts of chemicals easily traverse the placental barrier, and antidepressants are no exception. While the use of drugs like Prozac during pregnancy has been linked to cardiac defects and behavioral changes in children, none of the research done in humans can ethically test for cause and effect. But with more than 16 percent of American women currently taking antidepressants, the need to fully suss out the long-term repercussions of these early chemical exposures is ever-growing.

Now, researchers have unveiled an unexpected ally in their search for understanding: a striped, diminutive minnow called a zebrafish. According to a new study published today in the journal PNAS, developing zebrafish embryos exposed to the active ingredient of Prozac are less equipped to cope with stress later in life—and these effects are passed on through future generations. While the results have yet to be repeated in human populations, they may prompt a shift in our outlook on the prescription of antidepressants during this vulnerable period.

In spite of their stripes, zebrafish are far more fish than zebra. But we have more in common with these mighty minnows than you might think: About 70 percent of human genes have an obvious zebrafish counterpart. Like us, zebrafish respond negatively to stressful events and release many of the same hormones—some of which are even more comparable to those in humans than those produced by rodents.

“The overwhelming evidence today supports the value of zebrafish for modeling complex disorders, including schizophrenia, depression, and anxiety,” explains Allan Kalueff, a neuropharmacologist who studies zebrafish at Southwest University in China, but did not participate in the new research. “There is a striking similarity when it comes to drug responses.”

To mimic the medicinal milieu of the human fetal environment, study author Marilyn Vera-Chang, a biologist at the University of Ottawa in Canada, first exposed broods of newly-fertilized zebrafish eggs to fluoxetine, an antidepressant commonly marketed under the brand name Prozac. She then waited patiently as the eggs hatched into juveniles and matured into adults—a six-month process—and measured their chemical and behavioral responses to stress.

Zebrafish embryos are transparent, making it easy to observe their development. Mothers can lay up to 200 eggs a week. Photo Credit: Despoina Chrysostomou, Wikimedia Commons

Measuring stress in zebrafish isn’t trivial: These little fish aren’t particularly chatty about their feelings. Without saying a word, however, zebrafish can still speak volumes—chemically, that is. Just like humans, zebrafish produce the stress hormone cortisol in response to taxing situations. Cortisol is a body’s way of signaling that something’s amiss, so resources can be diverted to weather the storm. Like many other chemicals, cortisol operates on a Goldilocks principle. Too much cortisol puts the body on constant high alert—a state that’s been linked to depression. Too little, however, leaves an animal ill equipped to process stress, and can even lead to diseases characterized by extreme fatigue.

When Vera-Chang measured the zebrafish’s cortisol levels after they’d had a brief, nerve-wracking experience—being suspended out of water—she found that fish exposed to fluoxetine as eggs produced less cortisol compared to their untreated counterparts. Even when left to mind their own business, treated fish had less of the hormone coursing through their bodies.

It was a striking result. The adult zebrafish had spent the past five-plus months Prozac-free—and yet, the one-time exposure had blunted their stress response systems in a lasting way.

To see how this hormonal flux affected behavior, Vera-Chang next plopped individual zebrafish into a strange new environment—a fresh tank of water—to see how they’d react. Normally, in this situation, zebrafish spend a minute or two zipping around the bottom of their cage, searching for an exit. After the nerves have worn off a bit, they’ll tentatively begin to venture into the top half of the tank.

And that’s exactly what Vera-Chang saw—at least, in the fish that had spent their early development Prozac-free. Those who had been exposed to fluoxetine, on the other hand, remained stalwart bottom-dwellers. “It’s like they didn’t have energy to keep exploring,” Vera-Chang explains, “as if they were experiencing burnout.”

But the most surprising results were still to come. When the fluoxetine-treated fish had offspring of their own, they, too, produced less cortisol and were less eager to explore their tanks—despite never having seen the Prozac themselves. And, amazingly, when these zebrafish gave rise to another generation, the effect was still there. Somehow, the single exposure the first set of zebrafish had experienced during development was being passed down through the generations like an insidious inheritance.

Eventually, three generations down the line, the behavioral effects faded. But even at this juncture, cortisol remained low. “This is like your grandparents influencing your behavior, and your great-grandparents influencing your hormone levels,” explains study author Vance Trudeau, a neuroendocrinologist at the University of Ottawa.

It’s still unclear what these differences mean, but the fact that the changes were inherited from generation to generation at all might spark concern. While more work is needed, the researchers theorize this may be the result of epigenetics—a phenomenon in which chemical markers are added to DNA, altering the expression of genes without affecting the underlying sequence. In recent years, several studies have indicated that epigenetic modifications can be passed on to future generations, and this new study may be yet another example.

“We have to think about how we’re living our lives,” Vera-Chang says. “It’s not just us that are being affected by our actions.”

About 10 percent of Americans, and over 16 percent of American women, currently use antidepressants. Fluoxetine, or Prozac, is an especially common selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, or SSRI. Photo Credit: Tom Varco, Wikimedia Commons

However, researchers are quick to caution that it’s too early to jump to conclusions about human populations. Working with zebrafish makes it possible to conduct in-depth experiments that can’t be done in people—but analogs between the two species have their limits.

For one thing, humans who take antidepressants do so for a reason: to treat mental illness. All the fish in this study were healthy, making it tough to evaluate how a drug might traverse the barriers between a depressed mother and her child, explains Judith Homberg, a behavioral neurogeneticist at Radboud University in the Netherlands who did not participate in the research.

“We can replicate anxiety and depression to an extent in animal models,” explains Tim Oberlander, a developmental pediatrician at BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute in Canada who did not participate in the new research. “But ultimately, the human experience needs to be recognized as a unique thing.”

Additionally, incubating fish eggs in a petri dish is only a partial proxy for the placenta, says Homberg. Placental function itself could be affected by fluoxetine, meaning there could be other, indirect effects on a human fetus.

Still, a Prozac bath may not be terribly far off the mark. The uterine environment isn’t the only source of indirect exposure to antidepressants: Fluoxetine is one of many chemicals that have been found in water surrounding urban centers. “The bioecological impact of this study is very important,” Kalueff, the Southwest University neuropharmacologist, explains. “This tells us what could happen to children who drink fluoxetine-enriched water in big cities.”

Unfortunately, we’re still waiting on some of the most critical, human-centric data. Prozac first hit the market in the 1980s; as such, we’re only about one-and-a-half generations into use, Trudeau explains. As things stand, there’s some evidence that children of mothers taking fluoxetine during pregnancy are more withdrawn or anxious, but there isn’t yet data on whether the effects persist into subsequent generations.

A young zebrafish. While zebrafish don't physically resemble humans, the two species are very genetically similar, and both produce cortisol in response to stressful events. Photo Credit: Nikita Tsyba and Azamat Bashabayev, Wikimedia Commons

In the meantime, studies like these are essential for generating awareness, says Veerle Bergink, a psychiatrist and obstetrician-gynecologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai who was not involved in the new find. “These findings show clearly that this is a topic that warrants further investigation in humans,” she adds. “We need to have these discussions. It’s a medical issue, but it’s also a societal issue.”

Ultimately, the researchers emphasize that results of this study aren’t prescriptive. While antidepressants may have their downsides, depression during pregnancy is also potentially damaging to a growing fetus. Women faced with this choice often find themselves saddled with a difficult decision—but every case is different. Concerned mothers-to-be should always engage in a careful risk and benefit evaluation with their physicians.

“There are many women who really need this medication to maintain mood stability,” Bergink advises. “For some women, it may be the best option to continue medication. However, there are also women for whom it may be a good option to see if they can taper, or seek alternate treatment, such as psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness based therapy, or group support, among others.”

Oberlander agrees: There’s not going to be a one-size-fits all solution. “Is the treatment better or worse than the condition itself?” he says. “That’s the core question that we need to figure out urgently.”