It was the winter of 1997, and as my grandmother hung up the phone, tears gradually began to stream down her face. Another one of her friends, a close one, had died. I wrapped my arms around her waist and hugged her as she cried. It was the first time in my life that I can remember not just feeling sad for someone, but feeling sad

with that person. It was a powerful memory of empathy for me.Psychologists refer to empathy as a social-emotional skill, a term for the cognitive skills that guide our social and emotional behaviors. Social-emotional learning has recently become a popular topic in education reform, among both education researchers and educators interested in its pedagogical applications. A large body of research has shown that

With the rise of personalized learning and digital education tools for math, history, science and other core content areas, there has also been the development of social-emotional digital games. My initial query revealed approximately two dozen social-emotional apps available for download on the App Store. Some apps focus on emotional intelligence; while others focus cognitive brain breaks or empathy. Most of the apps focused on identifying emotions target younger children, while the games geared at understanding the perspectives and experiences of different people could be used by teenagers or adults. However, the presence of these games on mobile platforms makes them accessible to a much wider group of people.

Over the past two years, low-income families’ access to smartphones has increased from 27% to 51%, closing the “app gap” slightly faster than the disparity between high and low-income home internet access . Mobile platforms appear to have more potential to level the playing field of access to digital educational tools. Simultaneously, the

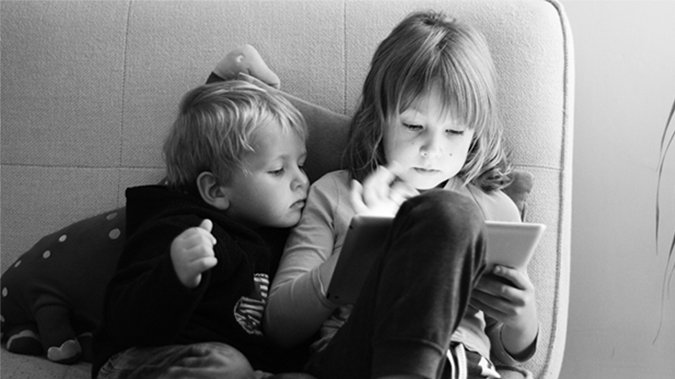

time children ages 8 and under spend on mobile devices has tripled since 2011 . But according to researchers at the University of California, the more time children spend in front of the screen could be inhibiting their ability to read social cues . So, if you are like me, it can be difficult to fathom learning empathy or other social-emotional skills from technology instead of human interaction, like I did with my grandmother.While some may be skeptical of social-emotional apps, there are certain scenarios in which they can be quite powerful. Speech-language pathologists often use these games to help children on the autism spectrum learn nonverbal cues to benefit social interactions. One program, The Social Express, is a series of interactive webisodes and apps that can be used by the learner independently, or with a teacher in a group. The Social Express allows learners to engage in a variety of social situations and adds a level of comfort that would be inaccessible without the game’s removal from reality. The app places a user in different social scenarios, often focusing on social skills that those with autism may struggle with, such as eye contact. Even though the app can improve a child’s behavior in social settings, parents and educators should employ the app as a supplemental, not primary, solution.

Not only are apps being used to teach social-emotional skills, but so are beloved children’s television characters. A few years ago, WGBH and Tufts University transformed the children’s television show Arthur into an interactive, digital comic book. Teachers paired 1 st and 4 th graders together to complete lessons that focused on prosocial behavior, positive decision-making, and character development. The computer game focused on these facets of social-emotional learning in an effort to proactively prevent bullying. In addition to the engagement of a game, it was effective because Arthur prompted children to have discussions with their peers about the dilemmas in the story. Thus, the verbal reflection with peers and a teacher about situations in Arthur improved social-emotional literacy. Results from a study evaluating the game’s efficacy revealed that children demonstrated increased awareness, understanding, and vocabulary about bullying .

However, there are cases where social-emotional games and programs can be used to manage students in ways that may not be beneficial to child development. The game Zoo U recreates common social scenarios at school, and children pick which dialogue option for their character to express in a tough social situation. The program provides educators with an assessment of a student’s competency in different social-emotional areas: emotion management and identification, impulse control, empathy, cooperation, communication, social initiation, and problem solving. The assessment provides concrete examples for teachers to target and improve specific weaknesses that the assessment identified. But assessments often become a student’s label for a teacher, especially when a teacher lacks the time and resources to spend quality time with a student. A seminal study by Robert Rosenthal at Harvard found that giving a teacher a label of a student’s intellectual capacity affects how that teacher instructs them ; teachers gave students with a label of intellectual growth more positive feedback, overtly and subtlety, throughout the learning process. Providing an assessment about a student’s level of empathy, for example, could provide a teacher with a label that could be misinterpreted as a character flaw.

While social-emotional apps may present a way for those with autism to learn social cues in a safe environment, the apps could also encourage a quick-fix solution to a behavioral problem in cases when medical professionals should be consulted. Though social-emotional apps can proactively address bullying and promote awareness on how to address it, other games may provide a social-emotional assessment of a child that runs the risk of misinterpretation. So, should social-emotional apps solve children’s behavioral problems or should we be finding more holistic solutions? The current body of research suggests that methods to improve social-emotional outcomes must be comprehensive and use technology as a tool, not a solution.