Read an Ancient Jewish Scroll

- By Peter Tyson

- Posted 11.23.04

- NOVA

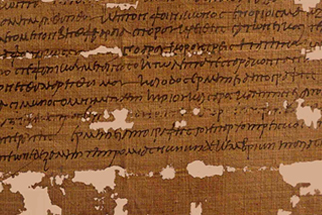

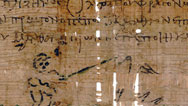

One of the most spectacular finds in Israel's Cave of Letters, as reported in NOVA's "Ancient Refuge in the Holy Land," was a packet of personal documents that belonged to a young Jewish woman named Babatha. Probably born around A.D. 104, Babatha became a woman of means who, by the time of her death around 132, owned valuable properties left to her by her father and her two husbands. In this interactive, have a close look at one of the 35 papyrus scrolls in the Babatha archive—a registration of land dating from the year 127—and get an inkling of what life was like for a well-to-do Jewish woman living under Roman rule in the second century. For more background on Babatha's extraordinary life, see the article "Babatha's Life and Times" below.

Launch Interactive

Launch Interactive

Watch as a 2,000-year-old cave document gets translated from ancient Greek into English before your eyes.

Babatha's life and times

In 1961, Yoseph Porath, a volunteer on an archeological expedition to what is now known as the Cave of Letters, along the west coast of the Dead Sea in Israel, stepped on a wobbly stone deep within the dusty cavern. It proved to be a giant step for our understanding of Jewish life 2,000 years ago. For beneath that stone, Yigael Yadin, the expedition's leader, having been alerted by Porath, discovered a bundle of papyrus scrolls. The cache turned out to be the valuable personal documents of a Jewish woman named Babatha, who lived and died in the second century A.D.

Babatha's documents—covering everything from a sale of property to a petition to the governor, from a court summons to a marriage contract—don't tell us what she looked like or what she felt or thought. But they do tell us, by standards of evidence unearthed from early Jewish history, an enormous amount about her life and times. As Richard Freund, an archeologist who led an expedition to the cave between 1999 and 2001, writes in his new book Secrets of the Cave of Letters, Babatha, who owned property both in Petra (in modern Jordan) and in En-gedi (in modern Israel), "revolutionized the way that we think about Jewish women in antiquity."

Born to own

Towards the end of the first century A.D., Babatha's father, Simon, settled in the port town of Maoza at the southern end of the Dead Sea (see map). At the time of Babatha's birth around A.D. 104, Maoza was part of the Nabatean kingdom. (The Nabateans were Semites of Arab stock who spoke Aramaic, the lingua franca of that time; their capital was Petra, the spectacular rock-cut city, which lay about 50 miles south of Maoza.) But in 106, the Roman emperor Trajan overran the Nabateans and made their land a Roman province, the Provincia Arabia.

While Babatha thus grew up under the yoke of an occupying power, she belonged, both by birth and by her two marriages, to a well-off stratum of regional Jewish society. But she was no aristocrat. As the historian Naphtali Lewis has written, "However we estimate Babatha's social position because of her wealth, by no stretch of the imagination can this rustic, illiterate woman be classed among persons in high places." Nevertheless, she was well-to-do, and judging from the breadth of languages used in the 35 documents in her archive, as well as by the legal maneuverings she seemed constantly to be involved in, she was well educated.

While Babatha may have been illiterate, she was no wallflower.

Babatha inherited land three times in her short life. First, her father Simon bequeathed a date palm orchard he owned to his wife and, upon her death, to his daughter. So Babatha may already have been a property owner when she married her first husband, a Maozan resident named Jesus. By 124, Jesus had left Babatha a widow with a young son—and left her property he owned in Maoza. (To learn more about these orchards, click on the image above to see Babatha's scroll.) Apparently not one to drown in her sorrows, Babatha married again by 125. Her new husband, Judanes, lived in Maoza but was originally from En-gedi, where he owned three date orchards. (He also had another wife, Miriam—polygamy was still permitted in Jewish life at the time.) When Judanes passed on around 130, Babatha seized his groves in En-gedi as a surety against a debt that he owed her.

Tough customer

This debt is one of many indications that while Babatha may have been illiterate, she was no wallflower. In fact, she was a shrewd businesswoman who controlled her own money and fought hard to retain it and her other material wealth. The documents show that when Judanes's daughter from his first wife got married, Babatha loaned Judanes 300 denarii (the silver coinage of the Roman period) toward his daughter's 500-denarii dowry. When, after his death, Judanes's estate failed to repay this debt or Babatha's own dowry (a widow was entitled to reclaim her dowry), she took possession of her deceased husband's En-gedi parcels.

This perhaps brazen act proved fateful. For one thing, it launched a legal battle over those properties with certain members of Judanes's family, in particular his first wife Miriam, that would hound Babatha for the rest of her life. More importantly, her new groves may have brought Babatha to En-gedi just as the largest Jewish revolt against Roman rule—the Bar-Kokhba rebellion, also known as the Second Revolt—broke out in the region centered on En-gedi. The last document in Babatha's archive, a summons, is dated the 19th of August in the year 132, the very year that the rebellion began.

Scholars surmise that Babatha either joined the revolt as a political sympathizer (as Yadin thought), or that she unwittingly got caught up in events during a possible visit to Judanes's orchards in En-gedi (as Freund thinks). Judanes's first wife Miriam had a family connection to a man named Yehonathan, who was thought to have been the rebel leader Bar-Kokhba's commander in En-gedi. Freund hypothesizes that when the outbreak of the rebellion made life in En-gedi dangerous, Miriam, despite having differences with Babatha over Judanes's land, may have arranged through Yehonathan to send Babatha to the relative safety of the cave. Miriam's daughter by Judanes, a young woman named Shelamzion, may have been close to Babatha and even accompanied her to the cave, for Shelamzion's marriage contract and other important documents were found in Babatha's archive.

The end

For whatever reason, Babatha appears to have ended up in the Cave of Letters in 132, a fugitive from Roman legions who went on to brutally suppress the rebellion, killing what may have been nearly 600,000 Jews. No doubt she planned to retrieve the documents she stored in a pit in the Cave of Letters and return to her prosperous life in Maoza and En-gedi, but she apparently died before she could do it. Was she enslaved or murdered by Roman soldiers, who had pitched a camp on the cliff above the cave to keep an eye on the insurgents they knew were hiding out there? Did she die of starvation in the cave? Indeed, were her remains among those found by another volunteer on Yadin's expedition in the so-called Niche of Skulls (see Stumbling Upon a Treasure)? We'll likely never know. All we do know is that her precious personal documents lay undisturbed for over 1,800 years, before their fortuitous discovery by Yoseph Porath in 1961.—P.T.

Sources

Further Reading

Freund, Richard A. 2004. Secrets of the Cave of Letters: Rediscovering a Dead Sea Mystery. Humanity Books.

Yadin, Yigael. 1971. Bar-Kokhba: The Rediscovery of the Legendary Hero of the Second Jewish Revolt Against Rome. Random House.

Credits

- Images

- © WGBH/NOVA/Gary Hochman

Related Links

-

Ancient Refuge in the Holy Land

Israel's remote Cave of Letters holds clues to a Jewish uprising against the Romans.

-

Origins of the Written Bible

William Schniedewind charts the rise of literacy in the Israelite world, making Holy Scripture possible.

-

The Bible's Buried Secrets

An archeological detective story traces the origins of the Hebrew Bible.

-

Papyrus

Scraps of writings from a garbage dump in ancient Egypt reveal what life was like 2,000 years ago.

You need the Flash Player plug-in to view this content.