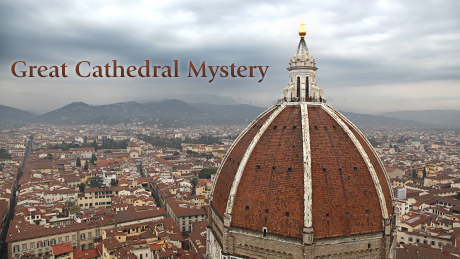

Great Cathedral Mystery

Master craftsmen explore how Florence's monumental dome was built nearly 600 years ago. Airing February 12, 2014 at 9 pm on PBS Aired February 12, 2014 on PBS

Program Description

Transcript

Great Cathedral Mystery

PBS Airdate: February 12, 2014

NARRATOR: It is one of the greatest engineering feats of all time, a miracle made of brick and mortar that defied the doubters and helped inspire the Renaissance: the dome of the Florence cathedral, built 600 years ago by a goldsmith, with no training as an architect, who dared to attempt the impossible.

ROCKY RUGGIERO (Kent State University): He constructs the dome at a time where the technology should not have permitted it. It just should not have been possible.

NARRATOR: Constructed of over four million bricks, weighing 40,000 tons, it's the largest masonry dome the world has ever known, yet the methods used to build it remain a mystery.

Now, a professor obsessed with the dome's secrets joins forces with a team of American bricklayers to put his theory to the test.

MASSIMO RICCI (University of Florence): You put there the bricks.

(Translated) I had to figure it out myself, because the builder didn't write anything down, and he didn't leave anything behind.

DAVE WYSOCKI (International Masonry Institute): This must be the way they have done it. This would be the only way that it makes sense.

NARRATOR: Secrets of the Duomo, right now, on this NOVA/National Geographic Special.

Florence, Italy: for centuries, travelers have been coming here to gaze at the wonders of the Renaissance. Six hundred years ago, this city experienced a creative explosion unlike any other. Visionaries like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo flourished here, in an atmosphere that celebrated imagination and innovation.

Many believe the Renaissance began with the completion of the city's most visible landmark, the dome on the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore. Built 60 years before Columbus sailed the Atlantic, without the use of modern machines or materials, the dome is still the largest of its kind in the world. It's an icon shrouded in mystery, because no one knows exactly how it was constructed.

Certain features of the dome stand out. It's in the shape of a pointed arch, with eight sides rising to a central point, topped by an enormous marble lantern. But there is more to it than meets the eye. The exterior tiles conceal walls containing over four million bricks, and what appears to be a single, solid structure is actually two domes, one inside the other.

The interior dome covers an open space nearly half the length of a football field, while the outer shell rises 10 stories atop cathedral walls, themselves 170 feet high.

Questions about how the dome was built persist to this day. Six centuries ago, how could builders work at such great heights? How could they know the eight sides would meet in the center? And how did the steep brick walls hold together without collapsing?

TIMOTHY VERDON (Cathedral Foundation Museum): With the dome, Florence moves into an entirely different dimension. The dome becomes the hub of a new city, of a new world. This is so soaring, so daring, so confident, so absolute a structure, it's like a work of God.

NARRATOR: But the dome is the work of a man, one of the most elusive and enigmatic geniuses of all time. His name was Filippo Brunelleschi. Trained as a goldsmith, he had no experience in architecture or building, yet he took on what seemed to be impossible: keeping 40,000 tons of masonry curving through the air without caving in to the floor below.

Experts are still trying to understand how he managed to defy gravity.

ROCKY RUGGIERO: He constructs the dome at a time where the technology should not have permitted it. How is it possible that he built the thing when he did? It just should not have been possible.

NARRATOR: By all accounts, Filippo Brunelleschi was a suspicious and secretive man. Unlike Leonardo, he left behind no notebooks, no drawings, no blueprints for later generations to study. So, for centuries, scholars have been trying to uncover the secret of Brunelleschi's dome.

Brunelleschi is so revered in Florence they hold a parade every year on the anniversary of his death. The destination: his tomb, within the great cathedral itself.

Leading the ceremony is Massimo Ricci, professor of architecture and engineering at the University of Florence. Ricci has spent 40 years of his life trying to understand the master's methods. For Ricci, Brunelleschi has become an obsession.

MASSIMO RICCI (Translated): The study of the dome is so difficult and so daunting, because it forces you to deal with the mind that created it. It's a direct relationship with a way of thinking that existed outside the norm. That engagement inspires a kind of fear, but at the same time, a great respect for him that is beyond measure.

NARRATOR: The mystery of the dome has taken such a hold on him that for nearly 25 years, Ricci's been building a dome of his own, in a park, in a residential neighborhood in Florence, employing what he believes to be Brunelleschi's methods.

He began construction in 1989. Since then, the model has served as an open-air laboratory, with Ricci playing the role of Brunelleschi, and crews of architecture students putting his ideas into effect.

Ricci insists his approach is the only way to answer questions that have mystified scholars since the Renaissance.

MASSIMO RICCI (Translated): I was the only one who felt the need to build a model on such a grand scale, to understand more deeply all of the secrets hidden within the dome.

NARRATOR: Now Ricci's experiment is at a crucial point in the process. With over 400 tons of masonry in place, the walls are beginning to bend inward, the pull of gravity is unrelenting, and the danger of collapse is very real. Soon, it could be too risky for students to continue the work.

MASSIMO RICCI (Translated): To understand the dome, you have to go through the problem of the bricklayers. Whoever doesn't do this is going to make a big fool of themselves.

NARRATOR: In the Renaissance, there were no lasers, computer-animated models, or detailed blueprints to guide the process. Builders relied on ropes to control the progress of the work. Ricci is convinced that the secret to the dome has something to do with a special way Brunelleschi used rope lines to establish how each brick should fit into place.

ANGELA: Non, troppa, troppa, troppa.

NARRATOR: Ricci's dome is one-fifth the size of Brunelleschi's, but still huge, large enough, he hopes, to prove his theory of the secret of the dome correct.

ROCKY RUGGIERO: I think, oftentimes, when you have an artist whose personality remains as vague as Brunelleschi's, inevitably what scholars do is to almost assume the role of the artist. What you're trying to do is to put yourself into the mind of the architect. Trying to find the secret of the dome is trying to find the secret of Brunelleschi.

NARRATOR: The search for that secret begins in the years just before the Renaissance. At the dawn of the 14th century, a kind of medieval arms race is raging between Florence and other emerging city-states, like Siena and Pisa, each trying to outdo the other by building bigger and bigger cathedrals.

TIMOTHY VERDON: Florentines are very creative people. They are also very competitive people. That means, among other things, they want to do what no one else has done.

ROSS KING (Author, Brunelleschi's Dome): And they decided that other cites in Tuscany, other cities in Italy, had grander temples than they did, and so they wanted to compete with them and, more especially, they wanted to outdo them.

NARRATOR: In 1293, the city leaders of Florence form a committee to oversee the construction of a new cathedral. They want theirs to be different from any other. Florentines dislike the look of the Gothic cathedrals that have been spreading across Europe for over a hundred years. They consider them too cluttered, with their walls propped up by flying buttresses and their many tall, pointed spires.

For inspiration, the committee looks to ancient Rome, in particular, to the classical temple honoring all Roman gods: the Pantheon. It was famed for its unrivaled dome, made of poured concrete. But such engineering technology had been completely erased by centuries of war, and it's the accepted wisdom of the time that no culture will ever rival the Romans in the building arts.

Florence is determined to surpass all architectural glories, past and present. Through the 1300s, the cathedral committee's vision for Santa Maria del Fiore keeps expanding: longer, wider, higher. Eventually, the committee's reach begins to exceed its grasp.

ROCKY RUGGIERO: They were really presenting themselves with a serious problem, because, in enlarging the church, what they are also enlarging is the crossing area of the church, essentially, where the two arms would intersect.

NARRATOR: Like many cathedrals, Santa Maria del Fiore is in the shape of a cross. The larger the church, the larger the area over the altar place needed to be covered by the dome.

ROCKY RUGGIERO: They eventually create a crossing space which measured 143-feet, 6-inches across. Today, in the 21st century, it would be difficult for us to cover, to roof, such a vast space. In the 14th and 15th centuries, theoretically, it should have been impossible.

NARRATOR: A mural depicting the cathedral, years before the dome was begun, shows what the committee had in mind: an enormous pointed dome with eight sides meeting at the top.

ROSS KING: There's no question it's going to be spectacular. There is just one catch: no one knows how they are going to build it.

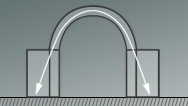

NARRATOR: What was so challenging about building a dome on this cathedral? After all, a dome is nothing more than an arch rotated 360 degrees. And, by 1300, Gothic cathedrals have been using arches and vaulting for over a hundred years.

How did they do it?

Medieval technology relies on wooden frameworks to hold the masonry until the final piece is put in place, the two sides pushing against each other allow the structure to stand on its own. This method is known as "centering."

ROCKY RUGGIERO: In the Middle Ages, if we're building a vault, okay, we build that wooden framework; we put our blocks, our bricks on top of it; we wait for the masonry to dry. Then, we make the sign of the cross, pull the wooden framework away and run like hell, because the failure rate on most of these vaults was about 50 percent.

NARRATOR: But this technology would not work in the Florence cathedral.

ROSS KING: The problem with the wooden centering for Santa Maria del Fiore was that it was going to be unprecedented in scale, if they built it. It would have been enormously expensive.

NARRATOR: The area beneath the dome is so high and so wide, just building the wooden framework to support the masonry would have taken hundreds of trees, years of construction and huge amounts of money. Unless someone, someday, invents a way to keep curving walls in place as they rise, the dome will never be built.

ROCKY RUGGIERO: I mean, for me, the most extraordinary thing about the construction of the cathedral is undertaking a project that you knew, fully well, you did not have the technology to complete.

NARRATOR: By the time Filippo Brunelleschi is born, the cathedral has already been under construction for 80 years, with no solution in sight to the problem of the dome. Brunelleschi spends his youth being trained, not as an architect or stonemason, but in a trade that continues to flourish in Florence to this day: precious metals.

It's a path followed in later years by many artists, including Donatello and Leonardo da Vinci.

SHOP KEEPER (Translated): He began in the workshop when he was 14 years old, his father's friend's workshop. He apprenticed until he was 17 or 18 and learned all the techniques typical of the Florentine tradition.

ROSS KING: To us, in the 21st century, that may seem a slightly odd way to get your start in architecture. But, in fact, you could have had no better training in the 15th century, to become an architect or a sculptor or a designer of any sort. They worked with gold, they worked with silver. They used their minds as well as their hands. They had to figure out how to make things work both practically and also aesthetically.

NARRATOR: Brunelleschi first attracts public attention in the year 1401. Just 23, he enters a competition to decorate the most revered building in all of Florence: the Baptistery. For centuries, Florentines, including Dante and the Medicis, have been baptized here. And the building needs a new set of ornamented bronze doors.

ROSS KING: And Filippo Brunelleschi, being very ambitious and very talented, threw his hat into the ring.

TIMOTHY VERDON: It's the most important artistic competition for a public work that everyone will see, that will immediately create fame and prestige. And he manages to become one of the finalists, along with another beginning master, Lorenzo Ghiberti.

ROSS KING: The competition involved casting a trial panel, making an experimental piece to show what you could do. So everyone was given the same amount of bronze and told, "Go away to your workshop and make us something."

MASSIMO RICCI (Translated): They produced two panels, which, luckily, still survive. In these two panels, there's a confrontation between the classical style of Ghiberti and the Renaissance style of Brunelleschi.

The Abraham of Lorenzo Ghiberti is very beautiful. He has a long, curly beard, flowing hair; the scene is very decorated, it's very rich in detail. The one from Brunelleschi is one of incredible humanism. That's already something new.

Look at the way in which Abraham wants to kill his son. While the Abraham of Ghiberti is just in his pose with the knife, and the son is there casually, almost like he's ready to be stabbed, in the one by Brunelleschi, he's taken his son by the throat, and you can see that he has placed his hand where the blood is flowing, because he wanted to stun the child, because he didn't want the son to feel the pain, when he stabbed him with the knife.

This is the creation of an incredible genius. Above all, it defines Brunelleschi as an artist. That is the difference this brought to the art of 1400 in the Renaissance. This is the Renaissance.

NARRATOR: Both panels are masterpieces, but Brunelleschi's vision may have been too far ahead of its time. The commission goes to Lorenzo Ghiberti.

ROSS KING: Losing the commission to Lorenzo Ghiberti, I think there's no question, hurt Brunelleschi very badly and, in many ways, shaped his career and the way that he proceeded after that.

TIMOTHY VERDON: Brunelleschi may or may not have understood why he lost, but certainly, from that point, Filippo Brunelleschi must feel that he has to carve out a new niche for himself.

NARRATOR: Following the competition, the disappointed Brunelleschi leaves Florence. Little is known about his life for the next 15 years, but it's clear he spends time in Rome, studying the ancient monuments. Some believe he's already preparing himself for a future challenge: building the dome on the Florence cathedral.

Here, in the nearby park, Massimo Ricci's dome is at a critical point. He and his helpers are preparing for its biggest test yet. With the walls increasing in height, Ricci is concerned about having his students continue the work, so a new team has arrived in town to help push Ricci's experiment forward.

MASSIMO RICCI: Good morning.

NARRATOR: They are all master bricklayers from the United States.

TOM WARD: Nice to meet you, sir.

DAVE WYSOCKI (International Masonry Institute): Dave Wysocki.

DON HUNT (International Masonry Institute): Don Hunt, nice to meet you.

BOB ARNOLD (International Masonry Institute): I think we're starting here.

NARRATOR: They're members of the International Masonry Institute, an organization that trains workers in the craft of bricklaying.

NATS: Quarter inch.

NATS: Half inch.

NATS: However many millimeters that is.

NATS: No inches here.

NATS: Millimeters.

NATS: Yeah, sorry.

NARRATOR: Each one has more than 20 years on the job. Not in Florence for the food or the works of art, they are here to lay some brick.

NATS: There you go, perfect.

NARRATOR: The bricklayers understand the basic structure of Brunelleschi's plan. The eight corners of the dome, where the walls meet, act like the ribs of the dome. Once these corner ribs meet at the top, they form powerful arches. Together with smaller interior arches, this goes a long way toward holding the 40,000-ton mass together.

BOB ARNOLD: Basically, it's a series of four Gothic arches, arches that come up this way. So, if you see that this rib, here…the opposite one there is going to come up, you know, like that. So, you've got a series of four gothic arches that all should meet in the middle. That's the key.

NARRATOR: Working on the model, the Americans will be confronting the key mystery of the dome: until the curving walls connect at the top, what keeps them from falling to the ground? And what magic did Brunelleschi use to defy gravity?

JONAS ELMORE (International Masonry Institute): You know, I've built a lot of things, from stadiums…baseball, football, but I've never ever worked on something like this. We use different mechanisms to hold arches in place. Then, once we are done, we take them out. But this is freestanding, which…I have never ever seen construction like this before.

NARRATOR: Their first task will be to literally "learn the ropes" and begin to understand Ricci's theory.

MASSIMO RICCI: They, they are very okay.

NARRATOR: By 1418, more than 100 years after work had begun, the enormous cathedral is almost complete. It's bigger than any other in the world, but without a dome, it is in danger of becoming the world's largest joke.

MASSIMO RICCI (Translated): It's clear the people of the city were worried about this problem. All the Florentines were talking about it. They knew very well that they risked looking bad in front of their rivals.

ROSS KING: They realized the building has got to the point where they cannot put off any longer how they're going to build this. And so they put forth a competition saying that whoever has any ideas about how on earth we can do this, we're open. It's sort of, "answers on a post card, please."

MASSIMO RICCI (Translated): They didn't have any idea what they were going to do.

NARRATOR: Proposals for the dome come pouring into the committee, but they all share a fatal flaw: they depend on using a wooden framework to keep the bricks in place during construction.

Only one candidate promises to build a free-standing, self-sustaining dome: Filippo Brunelleschi. He tells the committee he's figured out a way for the dome to stand on its own, even as it is curving inward.

ROCKY RUGGIERO: The financial advantage of that must have been extraordinary, but the skepticism was probably even greater, in the sense that, how could that be possible, what will prevent that structure from simply sliding out and caving in as we're building it?

NARRATOR: But there is a problem. The 41-year-old Brunelleschi has never built anything.

ROCKY RUGGIERO: When they get to that final piece—I mean this is really the climax of the entire two-century construction history of the church—who is this man working in jewelry, who now steps forward and says, "Look, I have the credentials, I have the knowhow, I have the inspiration to actually design this structure? And, I mean, would you have trusted him? I mean, I would not have.

NARRATOR: Perhaps, Brunelleschi's supreme self-confidence impresses the committee, because he clearly does not have all of the problems worked out in advance.

ROCKY RUGGIERO: I think that Brunelleschi had a very clear idea of how to build that dome, but realized that there were certain construction details that he could only figure out as the work was in progress.

ROSS KING: Filippo, being extremely secretive and not wanting anyone else to know his plan, said, "I'll show you how to do it when you give me the job. Give me the job and I'll begin doing it and you'll see that it works."

TIMOTHY VERDON: Everyone else had shown his plan. Brunelleschi refused. He said, "I know how to build it. Only I know how to build it. I've studied the ancient Roman structures. I already see it built." And so they said, "Well, you have to tell us something."

So he said, "Bring me an egg." And he said, "Anyone who can keep this egg standing upright on the marble tabletop will understand how I'm going to build the dome."

ROSS KING: Imagine all of these eminent master masons from all over Europe trying to get it to stand upright on its own. All of them fail.

TIMOTHY VERDON: And so they give the egg to Brunelleschi and say, "Show us what you mean. And Vasari, who tells this story in the 16th century, uses a very vulgar term. He says, "Pipo rupel cule vovo." "Pipo," Filippo's nickname, "broke the egg's ass."

So he breaks the bottom of the egg and they say, "Well, we could have done that, too."

ROSS KING: And Brunelleschi says, "Yes, and you would be able to build the dome if you know what I know."

NARRATOR: Seventeen years earlier, his radical vision may have cost him the competition for the Baptistery doors. This time, Brunelleschi keeps his idea secret for as long as possible, asking the committee to trust him.

ROSS KING: Had he told the assembled company his secret, it would have been something that they wouldn't have understood: a special brick pattern, a special kind of brickwork that he was going to use in the interior of the dome.

NARRATOR: In April, 1420, the committee comes to a decision. They choose Brunelleschi, along with two others, including his old rival, Ghiberti, to build the dome.

ROSS KING: If he ever was going to have a moment of doubt, I think that would have been the one, because he would have seen, up close and personal, the magnitude of the task that literally lay before him at that point, because he would have looked across this chasm, this yawning gap. He must have, at some level, gulped and thought, "Am I going to be able to do this?"

NARRATOR: Brunelleschi quickly emerges as the leader and takes on his first challenge: lifting the building materials 170 feet to the work platform above.

ROCKY RUGGIERO: Technologically, the means did not exist. Up until Brunelleschi's time, lifting devices were referred to generically as the "rota magna," or as the "great wheel," which was a large wooden wheel that looked very much like a modern gerbil cage, inside of which human beings would walk causing the wheel to turn. And as that wheel turned, it would coil a rope and that coiling would gradually then lift an object based on the lifting power of the people who are actually walking inside.

NARRATOR: Brunelleschi realizes that the old method could not be used in a project this large and a worksite this high. He invents a hoist that uses oxen, rather than people to raise and lower the loads.

ROCKY RUGGIERO: This is really Brunelleschi as the engineer, Brunelleschi as the inventor. They're turning a wheel that would turn a vertical shaft, and it, in turn, would have a series of cogged wheels that would then interlock with other cogged wheels, and so, as the oxen are moving in one direction, they could of course lift weight upward, okay?

But more importantly, Brunelleschi realized, "We're not going to have to only lift weights up, we're going to have to lower those weights, as well." And so, he introduces what is the first ever reverse gear, in history.

NARRATOR: Keeping the oxen moving in the same direction saves valuable time. The hoist raises or lowers material depending on which of two horizontal wheels locks into a vertical wheel on the drum holding the rope. When a load needs lifting, the bottom wheel engages, and the drum gathers rope in. When a load needs lowering, the top wheel is set in place to turn the drum in the opposite direction.

ROCKY RUGGIERO: By simply changing which of the wheels interlocked with the larger vertical one, you could then change the direction, technically, of actually lifting or actually lowering of the material down to the ground.

NARRATOR: The oxen could walk all day long in the same direction, keeping materials flowing to and from the workplace above.

ROSS KING: In 3,000 years of engineering, no one had ever done that. He pushed beyond a boundary that no one else had crossed. No one else had even got to that boundary; Brunelleschi crossed over it.

NARRATOR: Brunelleschi had solved the problem of lifting nearly 40,000 tons of material up to the worksite. Now, the former goldsmith has an even bigger challenge: connecting eight massive walls together to form the world's largest dome.

Florence holds its breath as the walls begin to rise. Around 1425, five years into the project, the bricks, by design, start to curve inward. Without a wooden framework to hold the weight, the project is entering dangerous, uncharted territory. The old methods of bricklaying would no longer work.

Most walls are built by simply laying bricks along straight lines, one after another, layer upon layer.

Russell Gentry, a professor of engineering at Georgia Tech, has studied Brunelleschi's methods.

T. RUSSELL GENTRY (Georgia Institute of Technology): So, if Brunelleschi had built the wall in the simple way you see here, you would have layers of brick and layers of mortar. And the layers of brick and layers of mortar are very simply separated by one another, and the layers of mortar represent planes of weakness through the wall.

What we see, here, is that the wall is leaning in, gravity is pulling it in towards me. And so a crack could form in one of the layers of mortar—the mortar is weaker than the brick—and the whole thing could rotate, and all of this brick could fall in.

NARRATOR: The time had come for Brunelleschi to share part of his secret plan with the world.

ROSS KING: That's the point in the building where support of some sort was always needed. And Brunelleschi had to begin using this special pattern of laying bricks that he, himself, seems to have invented.

NARRATOR: In Brunelleschi's new design, horizontal bricks are interrupted by others set vertically. Instead of continuing in one straight line, the bricks zig-zag. In the area between the two domes, that pattern is visible today, but only in small patches that remain unplastered.

In Italian, the design is called spina pesce, "spine of the fish." English speakers call it "herringbone."

BOB ARNOLD: I think we're having some spina pesce for dinner.

NARRATOR: The herringbone design is even easier to spot in Massimo Ricci's dome. The pattern is simple, and it's a method the American bricklayers catch on to rapidly.

DAVIDE: Okay. Perfetto.

NARRATOR: They lay the vertical bricks first. These are the spines. Once the spines are set, the horizontal bricks are then wedged in between the spines, row after row. In all their years of working, the Americans have never seen bricks laid quite this way.

TOM WARD: It's completely different. The techniques are definitely, definitely way different than what we're used to. This system is pretty amazing really.

NARRATOR: The vertical bricks in the spina pesce pattern block the mortar's planes of weakness. This prevents large sections of wall from separating—or sheering—and tumbling to the ground.

DON HUNT: If everything was laid horizontally, and you just brought it in slowly, each time, you would always have a sheer point, the sheer plane, where that could slide off; where, here, you don't have any single sheer point anywhere. It's all tied together a million times.

NARRATOR: The herringbone brick pattern is so untested at the time, Brunelleschi has to convince the cathedral board and the workers to allow him to use it. Once again, Brunelleschi is going against convention. He's also asking his workers to trust him with their lives.

ROSS KING: They were working around about 220, 230 feet in the air, and they were literally hanging over an empty space, where, if they fell, it was certain death. And, so, Brunelleschi certainly needed to have his men have faith in him. And they, they needed to believe that Brunelleschi knew what he was doing.

NARRATOR: Brunelleschi must have done something to convince the workers to trust this new method. But what?

The answer may lie in a building that sits just behind the cathedral, in the very shadow of the dome. It was built as a theater in the 1800s. Many years later, it was converted into a parking garage.

While renovations were going on to build a new wing of the cathedral museum, archaeologists dug out centuries of landfill, and discovered buried treasure: what now appears to be a hole in the ground would have been a free-standing structure in the 15th century, the remains of a dome, perhaps left there by Brunelleschi himself.

Professor Francesco Gurrieri of the University of Florence is overseeing the discovery.

FRANCISCO GURRIERI (University of Florence/Translated): Here it is.

ROSS KING: It's amazing.

FRANCISCO GURRIERI (Translated): This is the famous little dome. It was discovered in November, 2012, and it surprised the world of architecture.

NARRATOR: The top has been lost to time, but the inward curve of the walls remains. The little dome's base is constructed of sandstone; the brickwork only begins a third of the way up the wall. This proportion mirrors exactly the design of the cathedral dome, and the brickwork is done in a herringbone pattern.

FRANCISCO GURRIERI (Translated): I was immediately excited about it, because, having recognized the presence of the herringbone, I immediately connected it to Brunelleschi's technique.

ROSS KING: And do you think Brunelleschi stood here and said, "This is how I'm going to do it, this is the secret to building the dome?"

FRANCISCO GURRIERI (Translated): Yes, it's very probable that during the construction, Brunelleschi was here to demonstrate the use of the herringbone method. Yes, I think this is the model.

NARRATOR: But the new discovery features one obvious difference: it's round, while the cathedral dome appears to have eight individual walls. But appearances can be deceiving. Brunelleschi uses the spina pesce pattern to create a dome that looks like an octagon, but is actually one continuous spiral.

RUSSELL GENTRY: So, we're here looking at the corner of Massimo's dome, and what we can see behind the corner is we see the start of the bedding of the masonry, and as we go up, we can see the bricks in the spina pesce pattern. And if you watch carefully, you can see that they start here and they wrap up around, behind the corner, and continue uninterrupted from one face of the dome to the other face of the dome.

NARRATOR: By simply turning some bricks on their sides, Brunelleschi establishes a new pattern—and achieves two important goals: preventing cracks from spreading and binding the eight walls into one unified mass.

The spiral form resists the forces of gravity more effectively than an eight-sided dome. For many, spina pesce is the secret of the dome, but the construction of the dome involved many secrets, something the American bricklayers have come to understand from their time with Massimo Ricci.

NATS: Look at that! That's one piece.

NARRATOR: After two weeks on the job, they're ready to compare their work to the real thing.

The interior dome is completely covered by a religious mural.

NATS: Wow!

NARRATOR: The area between the shells offers only glimpses of key elements.

NATS: This is a corner rib. See that?

NATS: Yes.

NATS: This would be, and that would be an interior rib.

NARRATOR: And plaster conceals all but a few patches of brickwork.

NATS: You can still see, here, here's a good illustration of spine pesce.

NATS: Oh, man. This is unbelievable.

NATS: This is scary looking, isn't it?

NATS: It really is.

NATS: We can't be complaining about anything over our little one-fifth scale about 10 feet off the ground anymore.

NATS: No.

NARRATOR: On the way down, the workers notice something that escapes all but the most experienced eye.

NATS: You see this, guys? See how this is coming up to the center, just like on the model? See that? Both of these? That's the horizontal arch right there.

NARRATOR: The bricks are sloping down from the corner ribs toward the centers of the walls. The massive scale of the dome makes it difficult to see, but the Americans recognize its significance from Massimo Ricci's model.

The important feature, barely visible in Brunelleschi's dome, becomes clear in Ricci's model. The tops of the walls don't follow a straight line as they go up; they dip from corner to corner. Within each wall, this creates an inverted arch, one of the most stable forms in architecture. These arches, combined with the spina pesce pattern, keep the bricks firmly in place, directing the weight of the masonry downward through the walls, preventing them from collapsing inward.

It's an ingenious design, and Ricci struggled for years to figure out how Brunelleschi made it work and how he insured that the walls all met perfectly at the top, nearly 300 feet above the ground.

Ricci was sure the answer lay in one of the primary building technologies of the time, rope lines, which Renaissance builders used to guide their work. If Ricci could figure out how Brunelleschi set up his ropes, he could unveil one of the dome's most overlooked secrets.

He knew the guide ropes must have been attached to a large platform built into the base of the dome, but in what pattern?

MASSIMO RICCI (Translated): I had to figure it out myself, because Brunelleschi didn't write anything down and he didn't leave anything behind.

NARRATOR: Ricci sketched out hundreds of possible designs, trying to unlock Brunelleschi's secret. Then he heard about a 600-year-old document stored in the Florentine State Archives.

It's a drawing done on parchment, about five years after work on the dome began. It's the only surviving eye-witness sketch of the dome's construction, and it's a scathing criticism of Brunelleschi's methods. The critic, named Giovanni di Prato, detailed what he considered to be Brunelleschi's mistakes. The dome, he warned, was doomed to collapse.

MASSIMO RICCI (Translated): He's really tearing him apart. He's trying to tear apart Brunelleschi, but, in effect, Giovanni di Prato wasn't able to understand much of what Brunelleschi was doing.

NARRATOR: Di Prato may not have understood Brunelleschi's system, but he was thorough in his observations. He carefully sketched the rope lines Brunelleschi was using to guide the construction. More importantly for Ricci, di Prato also drew the work platform to which the ropes were attached. Here, Ricci noticed something unusual: a thin line curving around the platform. To Ricci, it looked like a flower. And he immediately saw it as the key to Brunelleschi's system.

MASSIMO RICCI (Translated): When I saw the platform with the flower drawn on it, I said, "Well, I'm at the right place!"

NARRATOR: Ricci incorporated the flower into the work platform of his model, using it to guide each wall's construction. Rope lines are important building tools even today, and the Americans catch on quickly to Ricci's system.

One worker, stationed on the platform, hooks a line to the flower. Another, on the top of the wall, handles the other end of the rope. The rope controls the angle and the height of the bricks.

TOM WARD: Can you see now?

Hey, can you hold that there for a second? Concentrate on this one, right here, that's moving, the one that Bob has a hold of. It sets the line up for that spina pesce, so it's, essentially, their guide.

NARRATOR: And that's why the shape of the flower is so important. As the platform worker moves the line along the flower, the rope transfers the curve of the flower to wall. This creates the inverted arch.

The walls may be strong, but for the dome to work, they must meet together at the top. One small miscalculation, repeated hundreds of thousands of times, would lead to disaster.

BOB ARNOLD: Here's the angle. And as you go up, it should follow that all the way up.

Say, if this one's not correct, as you get that dome closing up to the top, it's not going to want to hit in the middle. So you might, you know, the dome might be this way or it might be this way.

NARRATOR: How could Brunelleschi know his dome was on the right track? The answer is in the lines. Criss-crossing from wall to wall, they establish the center point. And before any rope line guides a brick into place, it must pass through that center.

Brick by brick, the walls of Brunelleschi's dome rise until they meet at the top. Nearly 300 feet in the sky, and the dome is complete.

For Ricci, the ropes guiding the bricks provide the real key to the mystery of the dome.

MASSIMO RICCI (Translated): I can say with utmost certainty this is the true secret of Santa Maria del Fiore.

NARRATOR: After two weeks of working on Ricci's dome, the Americans seem convinced by his experiment.

DAVE WYSOCKI: This must be the way they have done it. Without putting a support underneath there, this would be the only way that it makes sense.

DON HUNT: It's the flower and it's the herringbone pattern; those are the two things that solve the puzzle. You wouldn't be able to build a dome like that without those control measures.

NARRATOR: Massimo Ricci has now been working on his dome longer than it took Brunelleschi to build the original. His model will remain an open laboratory for those studying Brunelleschi's methods—and as an argument for the importance of the flower.

It's possible that Ricci, unlike his hero, will never see his work finished.

ROSS KING: If you look at the dates of the building, 1420 to 1436, 16 years. That's the blink of an eye. That's very, very quick. And it's wonderful to think that he saw it completed. He was able to look at it. He was able to walk past the building and think to himself, "I built that. I did that."

TIMOTHY VERDON: With the dome, Florence moves into an entirely different dimension. The dome becomes the hub of a new city, of a new world. It is the expression of a self-confidence that it no longer knows limits.

People need works that can speak to them of their own capacity to dream. Brunelleschi's dome is perhaps the biggest of those works in the history of world art.

Broadcast Credits

- WRITTEN, PRODUCED & DIRECTED BY

- David Murdock

- EDITED BY

- Daniel Sheire

- DIRECTORS OF PHOTOGRAPHY

- Erin Harvey

Rene Heijnen - NARRATED BY

- Jay O. Sanders

- CO-PRODUCER

- Katie Bauer

- CONSULTING PRODUCER

- Gianluca Tenti

- ASSOCIATE PRODUCER

- Anisa Peters

- SOUND RECORDISTS

- Saverio Damiani

- Buckshot Sound

- ADDITIONAL CAMERA

- David Murdock

Gary Grieg

Dave Yoder

Katie Bauer - OCTOCOPTER

- Helivr

- JIB CREW

- Movie People

- FIXERS

- Once – Extraordinary Events

Matteo Castelli - MUSIC

- Christopher Rife

- ANIMATION

- Mothlight Creative

- PRODUCTION MANAGER

- Jessica Cutler

- ONLINE EDITOR

- Daniel Sheire

- COLORIST

- David Markun

- AUDIO MIX

- Bob Bass

- ASSOCIATE RESEARCHER

- Shraddha Chakradhar

- TRANSCRIPTION

- Patti Pancoe

- TRANSLATORS

- Laura Depalma

Helen Farrell - ARCHIVAL MATERIAL

- Alinari Archives / Corbis

Arte & Immagini srl / Corbis

Benozzo di Lese di Sandro Gozzoli / Getty Images

Bettmann / Corbis

Paolo Cipriani / Getty Images

Corbis

David Grubin Productions

DEA / G. Dagli Orti / Getty Images

DEA / G. Nimatallah / Getty Images

DEA Picture Library / Getty Images

Historical Picture Archive / Corbis

Image Source / Corbis

iStockphoto / Hulton Archive

The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource

Alfredo Dagli Orti / The Art Archive At Art Resource, NY

The Piermont Morgan Library / Art Resource, NY

Scala / Art Resource, NY - SPECIAL THANKS

- Antico Spedale del Bigallo

Archdiocese Of Florence

Archivio di Stato di Firenze

Associazione Culturale Contrada Alfiere

Associazione Filippo di Ser Brunellesco

Associazione il Fiorino

Jim Atkins

Paolo Bianchini

Sonia Cafaggini

Michele Cavallo

Gianluca Chegai

Gianni Cicali

The City Of Florence

Comune di Bagno a Ripoli

Cotto REF

Lucia De Siervo

Rossella Donati

Florence Municiple Police

Giuseppe Giari

Mariagrazia Giuliani

Franco Gizdulich

Grand Hotel Cavour – Firenze

Margaret Haines

The International Masonry Institute

Gregory Jenn

Franco Lucchesi

Piero Marchi

Ambra Nepi

Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, Firenze

Massimo Rubino

San Firenze Suites

Scuola Professionale Edile di Firenze

Andrea Sichi

Dave Sovinsky

Stefano Strazzari

Carmela Valdevies

Paul Robert Walker

Carla Zarrilli

Andrea Zufanelli - EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC TELEVISION

- John Bredar

Jared Lipworth - NOVA SERIES GRAPHICS

- yU + co.

- NOVA THEME MUSIC

- Walter Werzowa

John Luker

Musikvergnuegen, Inc. - ADDITIONAL NOVA THEME MUSIC

- Ray Loring

Rob Morsberger - CLOSED CAPTIONING

- The Caption Center

- POST PRODUCTION ONLINE EDITOR

- Spencer Gentry

- DIRECTOR OF PR

- Jennifer Welsh

- PUBLICITY

- Eileen Campion

Eddie Ward - SENIOR RESEARCHER

- Kate Becker

- NOVA ADMINISTRATOR

- Kristen Sommerhalter

- PRODUCTION COORDINATOR

- Linda Callahan

- PARALEGAL

- Sarah Erlandson

- TALENT RELATIONS

- Scott Kardel, Esq.

Janice Flood - LEGAL COUNSEL

- Susan Rosen

- DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION

- Rachel Connolly

- DIGITAL MANAGING PRODUCER

- Kristine Allington

- SENIOR DIGITAL EDITOR

- Tim De Chant

- DIRECTOR OF NEW MEDIA

- Lauren Aguirre

- DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATE

- Lisa Leombruni

- UNIT MANAGER

- Ariam McCrary

- POST PRODUCTION ASSISTANT

- Brittany Flynn

- POST PRODUCTION EDITOR

- Rebecca Nieto

- POST PRODUCTION MANAGER

- Nathan Gunner

- COMPLIANCE MANAGER

- Linzy Emery

- BUSINESS MANAGER

- Elizabeth Benjes

- DEVELOPMENT PRODUCER

- David Condon

- PROJECT DIRECTOR

- Pamela Rosenstein

- COORDINATING PRODUCER

- Laurie Cahalane

- SENIOR SCIENCE EDITOR

- Evan Hadingham

- SENIOR PRODUCERS

- Julia Cort

Chris Schmidt - SENIOR SERIES PRODUCER

- Melanie Wallace

- MANAGING DIRECTOR

- Alan Ritsko

- SENIOR EXECUTIVE PRODUCER

- Paula S. Apsell

A NOVA Production by National Geographic Television Production in association with Camera One Productions.

© 2014 NGHT, LLC and WGBH Educational Foundation

All rights reserved

This program was produced by WGBH, which is solely responsible for its content.

IMAGE

- (Duomo, Florence)

- © National Geographic Television

Participants

- Jonas Elmore

- International Masonry Institute

- T. Russell Gentry

- Georgia Institute of Technology

- Ross King

- Author, Brunelleschi's Dome

- Paolo Penko

- Goldsmith

- Massimo Ricci

- University of Florence

- Rocky Ruggiero

- Kent State University

- Timothy Verdon

- Cathedral Foundation Museum

- Dave Wysocki

- International Masonry Institute

Preview | 00:30

Full Program | 52:37

Full program available for streaming through

Watch Online

Full program available

Soon