|

|

|

by Peter Tyson If there is a harsher place to live than a hydrothermal vent, it hasn't been found yet. Pitch darkness, poison gas, heavy metals, extreme acidity, enormous pressure, water at turns frigid and searing—this seafloor environment seems more like something from deep space than from our own deep sea. Yet amazing communities of life exist at hydrothermal vents and the so-called "black smoker" chimneys that, given the right conditions, rise above them like erupting stalagmites. Blind shrimp, giant white crabs, and a variety of tubeworms are just some of the more than 300 species of vent life that biologists have identified since scientists first blundered upon this otherworldly community two decades ago. More than 95 percent of these species are new to science.

Dark as night For starters, it's pitch black at such depths. Sunlight penetrates no farther than a few hundred feet down, leaving the deep-sea floor as dark as the deepest cave. With no sunlight, there are no plants; all vent life belongs to the animal kingdom. And with no plants, there is no photosynthesis. Biologists were flabbergasted when they first learned that creatures lived in total darkness at the seafloor. All other life ever identified, on land or in the sea, derives its energy either directly or indirectly from the sun. How, they wondered, did these animals manage without?

As if utter darkness were not enough, vent animals must contend with a witch's cauldron of deadly toxicants. Foremost among them is hydrogen sulfide, one of the principal ingredients of the broiling water spewing from vents and black smokers. While vent microbes thrive on the stuff, this gas is lethal to most other organisms, including the creatures that live within wafting distance. Yet not only do those animals survive it, they depend on it as intrinsically as they do on the microbes. Hydrogen sulfide reacts spontaneously with oxygen, so as soon as vent fluids come into contact with seawater, a swift reaction occurs, releasing energy. All that energy would go to waste if it were it not for the microbes. They harness that reaction and use carbon dioxide to make organic compounds that tubeworms, for example, need to live.

Vents and smokers also release a bevy of heavy metals. Besides being toxic substances, these particles can clog mouthparts and gills. Biologists are still trying to figure out exactly how vent animals cope with these. Several animals have metal-binding proteins in their systems, while others, like some polychaete tubeworms, appear to expel these toxics in mucus. Beyond the toxic gas and particles, vent water can also be extremely acidic. The pH of waters coming out of black smokers can be as low as 2.8, making it more acidic than vinegar. Biologists have seen "naked" snails around hydrothermal vents that could not form their calcium carbonate shells because the water was too acidic. Continue: Pressure's On The Mission | Life in the Abyss | The Last Frontier | Dispatches E-mail | Resources | Table of Contents | Abyss Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated October 2000 |

Menagerie at a hydrothermal vent.

Menagerie at a hydrothermal vent.

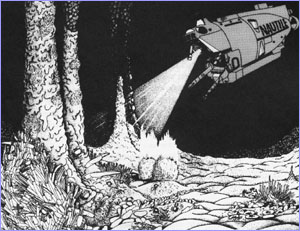

Sub illuminates smokers adorned with vent life.

Sub illuminates smokers adorned with vent life.

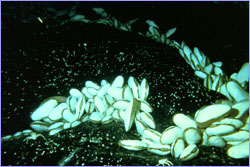

A string of clams winds across a vent.

A string of clams winds across a vent.

Temperature of this Juan de Fuca Smoker:

648°F.

Temperature of this Juan de Fuca Smoker:

648°F.  Deep-sea anemone clings to lava outcrop.

Deep-sea anemone clings to lava outcrop.