By Anthony Ha

[Note: Some movie spoilers within.]

If decades of science fiction have taught me one thing about being an astronaut, it’s that you have to watch out for existential terror and loneliness.

Movies like Sunshine and Interstellar are full of characters who lose their grip on reality after spending too much time alone. “Space Isolation Horror” even has its own page on the TV Tropes website.

Why is this such a common science fiction plot device? Maybe it’s an update to the old, mad scientist cliché—it’s pretty easy to draw a line between Frankenstein’s Colin Clive screaming “It’s alive!” and Sam Neill’s demonic glee in Event Horizon. But where the mad scientist fable usually argues there are some things man was not meant to know, the space isolation story suggests something inherently ill-advised about venturing beyond Earth’s atmosphere—that there are places man was not meant to go.

As the mechanic Kaylee puts it in the movie Serenity (2005), screenwriters seem convinced there’s an inherent risk of reaching “the edge of space,” seeing “a vast nothingness,” and going “bibbledy over it.”

Nothing quite so dramatic has happened in the real world—but the documentary Space: The Longest Goodbye examines a more mundane challenge: how astronauts on the International Space Station (ISS) struggle to remain connected to their old lives while spending months away from home, in cramped quarters, with unreliable internet. As NASA operational psychologist Al Holland notes in the film, understanding how crew members cope with a six-month tour on the ISS provides crucial data about the challenges facing a manned, three-year Mars expedition.

There are many proposals for such an expedition, but no certain plans. While we wait, we can look at science fiction for hints about the psychological risks posed by life in space, along with possible solutions.

Phoning home

The most obvious solution is one that’s migrated from sci-fi to reality: Astronauts on the ISS are already making Skype calls home. A company featured in The Longest Goodbye is even experimenting with bringing pre-recorded messages to life in virtual reality (VR).

But the occasional video or VR phone call isn’t the same as having a regular, physical presence in someone’s life. In the Black Mirror episode “Beyond the Sea,” astronauts transfer their consciousness to android replicas back on Earth, thus maintaining something almost like a real life with their families—they can be there for their children’s birthdays and try to maintain a romantic spark with their partners.

But however effective the technology, it can’t fully erase the distance between the mission in space and the family on Earth, as the episode’s tragic events make all too clear.

And when we’re talking about Mars or destinations beyond, the distances are simply too great for a synchronous conversation—it takes between 4.3 and 21 minutes for a radio signal to travel between Earth and Mars, depending on where the two planets are in their relative orbits.

Season four of Apple’s For All Mankind dramatizes these challenges, as workers in a Martian colony try to talk to family members back home through slow-loading, pre-recorded video messages. For those of us who already deal with dodgy internet on Earth, this might just sound like an annoyance. For the Martian laborers, however, it becomes a bitter reminder of how far they are from home, and how the colony’s class system has failed them.

Going virtual

Of course, VR can do more than dramatize a phone call. The dream would be something like Star Trek: The Next Generation’s holodeck, which can seemingly replicate any location in the known universe. The tech isn’t perfect—if anything, the holodeck seems to be continually malfunctioning, as safety measures get disabled and programs become sentient. But that never seems to scare off any of the Next Gen crew members.

Because the holodeck is awesome. While inside, Captain Picard can roleplay as the hard-boiled gumshoe Dixon Hill, Worf and Troi can take a romantic stroll along the Black Sea, and Lieutenant Barclay can even play-act a version of his life on the Enterprise—a version where he’s braver, more dashing, and beloved by all.

Unfortunately, it’s hard to think of existing technology that can conjure up physical locations and props out of nothing. A simpler version in Sunshine (2007) may be more achievable. In the film, a small crew is traveling to the heart of the solar system, transporting a bomb that they hope will reignite our dying sun.

As the distance from Earth grows and tensions rise between the crew, the on-board psychologist prescribes more time in the “Earth Room”—an enclosed space that surrounds anyone inside with footage of home, whether that’s a peaceful forest or a beautiful day at the beach.

Artificial friends

It’s worth remembering that astronauts usually aren’t alone alone. Instead, they’re living with other astronauts, doing their best to work together without getting on each other’s nerves. But those human crew members may not be the most consistent or reliable sources of companionship and support, especially if everyone’s been stuck together for months.

Consider the most iconic character in the most iconic movie about space: 2001: A Space Odyssey’s sentient computer HAL 9000, who’s both an essential crewmember on the spaceship Discovery, and a companion to its human astronauts. Both astronauts seem to have a richer friendship with HAL than with each other: he plays chess with them, he wishes them happy birthday, he seems like a solid friend—until he tries to kill them.

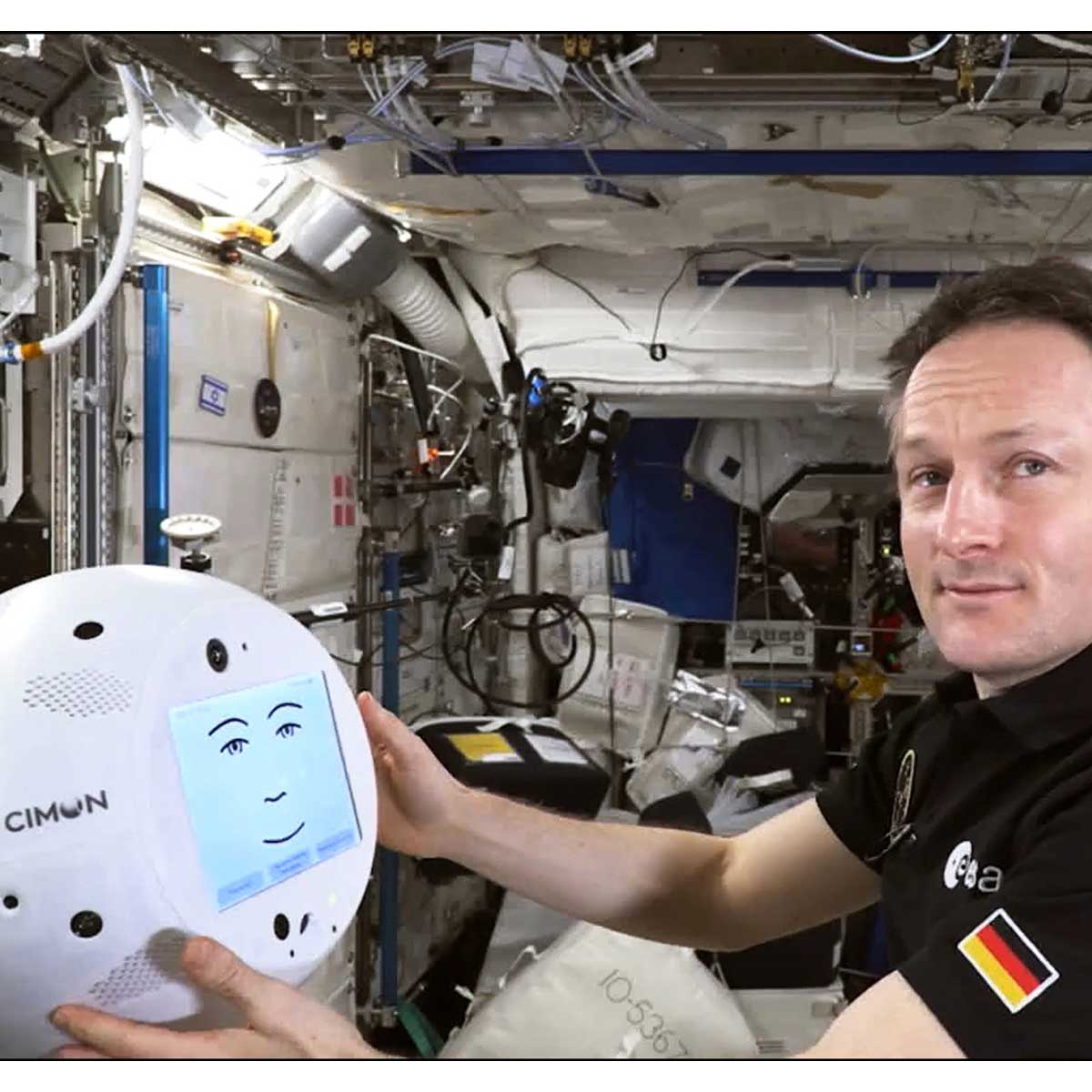

This might be one area where the current limitations in AI technology will serve us well. The real world’s floating, head-shaped CIMON robot [as seen top right] may only be able to offer limited conversational responses and facial expressions; no one would mistake it for a sentient being, any more than you’d mistake Siri or Alexa for a real person. But basic may be all that’s needed for astronauts to feel some degree of companionship and support, and at least no one has to worry about CIMON running amok.

Sleep it off

In the future, astronauts might even be able to avoid loneliness entirely by sleeping through the months or years of their journey between planets and stars. We see this in 2001, with most of the scientists on board the Discovery, and in Alien, with the blue-collar crew of the Nostromo. This has practical benefits—sleeping astronauts need less food and air—while also allowing them to skip from the beginning to the end of their journey.

In fact, the astronauts in Andy Weir’s novel Project Hail Mary are put into a coma specifically to avoid the psychological challenges of the 26-year(!) journey to Tau Ceti.

Then again, hibernation fails to save either the Discovery or Nostromo crew from the dangers of space. And as Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley survives into the Alien sequels, the technology isolates her in a different way. Trapped in a tiny escape pod, she drifts along, sleeping for decades and waking in an unfamiliar future, with everyone she knows already dead.

How to be alone

Space isolation stories aren’t just about confronting the terror of what’s out there. They can also function as a hall of mirrors, trapping protagonists with different versions of themselves—as Marion Zimmer Bradley did in her short story “Elbow Room,” and as the film Moon does to a set of clones (played by Sam Rockwell) on a lunar base.

And it turns out being alone, with only aliens or doppelgängers for company, isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It’s how Moon’s two Sam Rockwells come to understand their place in the universe. It’s how Alien’s Ripley discovers hidden reserves of strength. And it’s how 2001’s Dave Bowman achieves the cosmic transcendence of transforming into a giant space baby.

Anthony Ha is a New York-based journalist focused on the intersection of culture and tech. Currently TechCrunch‘s weekend editor, he was previously a reporter at Adweek and VentureBeat. In addition, his work has appeared in BuzzFeed and Engadget, and he co-hosts the Original Content podcast. Read his previous article for Independent Lens, “How End-of-Life Doulas are Changing the Conversation Around How We Die.”